In the last three decades of the 19th century, the field of American ceramics blossomed. From small potteries, which had previously created utilitarian wares unable to compete as equals with European imports, came a flowering of technical innovation and artistic invention. Yet compared to the visibility of American ceramic art’s mid 20th-century greats, such as the Abstract Expressionist Peter Voulkos, or the Finish Fetish artist Kenneth Price, the pottery produced during the Arts and Crafts period is comparatively obscure. In donating over 300 pieces of American art pottery by 80 potters and firms to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the painter Robert A. Ellison Jr. has transformed the Met’s holdings in this area.

These ceramics and commentaries on their economic, social and artistic contexts fill this volume, which is generously illustrated with 401 images. It is to be praised, too, for its efforts to ensure comprehension. Technical terms, some obscure even to those familiar with ceramics – the dust-clay process or cuerda seca technique, anyone? – are explained when necessary, making for inclusive reading. The stated aim of the book is to ‘impart a full understanding of American art pottery while celebrating the legacy of a visionary collector’. The latter intention is appropriate, but to conflate it with the former poses something of a problem. To collect as a private individual is necessarily to be partial – a quality Ellison is open about, saying: ‘I […] went with my eye for many things.’ (This frankness, although commendable, is occasionally wince-inducing – as when he remarks, ‘I always felt that if you don’t buy it, you have no impetus to learn about it.’) The earliest piece in the collection is dated 1876, the latest 1958, but the majority were made between 1890 and 1915; and it is in the uneven weighting of works across this time span that issues arise.

We begin with the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, hailed here as ‘the dawn of American Art Pottery’. Prior to this enormous fair, which featured an overview of world ceramics, the US industry relied heavily on English influence for both its style and manufacturing practices. At the exhibition, Japanese ceramics were praised for their diversity and finishes, Danish for their classical inspiration, and French for the newly mastered barbotine technique. Barbotine – from barboter (‘to daub’) – involves clay slip mixed with mineral oxides applied to ceramics with a brush in a painterly fashion to create impasto designs. The technique proved particularly influential, leading directly to the development and rapid popularity of America’s home-grown version. It was with barbotine that Rookwood Pottery came to prominence. Rookwood was the best known and longest surviving American art pottery, founded in 1880 and continuing until well after the Second World War. Its later underglaze-painted vases featuring floral motifs over soft gradations of colour were popular for so long as to be virtually synonymous today with the phrase ‘art pottery’. But we also learn of efforts to compete with industrial ceramics through the more affordable, serially produced work of the Fulper Pottery in New Jersey. Entering the art pottery market in 1909, Fulper’s VaseKraft line included a popular range of ceramic lamp designs; its commercial nous allowed it to survive until 1976.

The first self-identified ‘art pottery’ was the Chelsea Keramic Art Works of Massachusetts, founded by the Robertson family in 1872. They are most notable for Hugh C. Robertson’s invention of wildly popular matt glazes – hitherto never achieved by any potter in either the US or Europe – and his successful replication of the elusive Chinese sang-de-boeuf or oxblood glaze, the secret of which had been sought after in the West for centuries. These lustrous blood-red pieces are particularly striking, and the quantity in which they appear reveals Ellison’s particular passion for these pieces.

Vase (c. 1897–1900), George E. Ohr. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Equally evident is his fascination with George Ohr, the self-styled ‘Mad Potter of Biloxi’. Ohr’s bizarre oeuvre of slumped, asymmetrical and wilfully surreal pots, plus his legendary braggadocio – he priced his pots by their weight in gold – sets him apart from more well-mannered forebears. A victim of contemporary taste and his own eccentricities, he was overlooked in his time (he potted from 1880 to 1909) but is now highly collectible. In a departure from the standard division of labour, Ohr worked alone, from preparing clay to firing finished pieces, setting what is now widely considered a precedent for 20th-century studio pottery – particularly the more iconoclastic strands that developed in the mid 1950s.

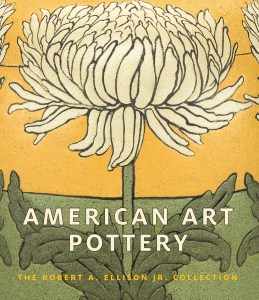

A chapter titled ‘Clay as a Social Force’ discusses what were often utopian enterprises based on William Morris’s belief in the ennobling influence of handicrafts, ideas about the health-giving properties of art, and increasing efforts to secure financial independence for women. The piece on the book’s front cover – a matte-glazed earthenware vase with a design of chrysanthemums produced by the Paul Revere Pottery in Boston – is both an outstanding object and a compelling artefact of social history. Founded by the philanthropist Helen Osborne Storrow to provide support for young women, the Pottery was run by Edith Guerrier and Edith Brown, whose partnership was then known as a ‘Boston marriage’. Brown provided master designs and taught the skills of pottery decoration to a high degree, as is amply illustrated in the finesse of this vase, decorated and initialled by one Ida Goldstein.

Vase (c. 1908–15), designed by Edith Brown and decorated by Ida Goldstein, Paul Revere Pottery. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Art pottery after the First World War until the late 1950s is covered in only the final chapter. More than three decades of making, over a period of dramatic social, economic and artistic change, are compressed together; what had been a steady pace becomes a gallop. Given Ellison’s tastes, there are inevitable omissions. The ‘heavy influence’ in the United States of the Englishman Bernard Leach and the Japanese potter Shoji Hamada is reduced to two paragraphs and one barely representative work by Antonio Prieto, while Peter Voulkos receives six pages. Neither Marguerite Wildenhain nor her fellow émigré Ruth Duckworth are mentioned, to name but a couple of examples that could have provided a more complete narrative. Taken on its own terms (to provide a ‘full understanding of American art pottery’), the book is at its best when covering the earlier period, the one most fully represented in Ellison’s donation. But as an exploration of a complex collection, and for shining a light on the period before the First World War in ceramic history, it makes for fascinating reading.

American Art Pottery: The Robert A. Ellison Jr. Collection by Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Martin Eidelberg and Adrienne Spinozzi is published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

From the December 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.