The Apse of Notre-Dame (1854), Charles Meryon. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

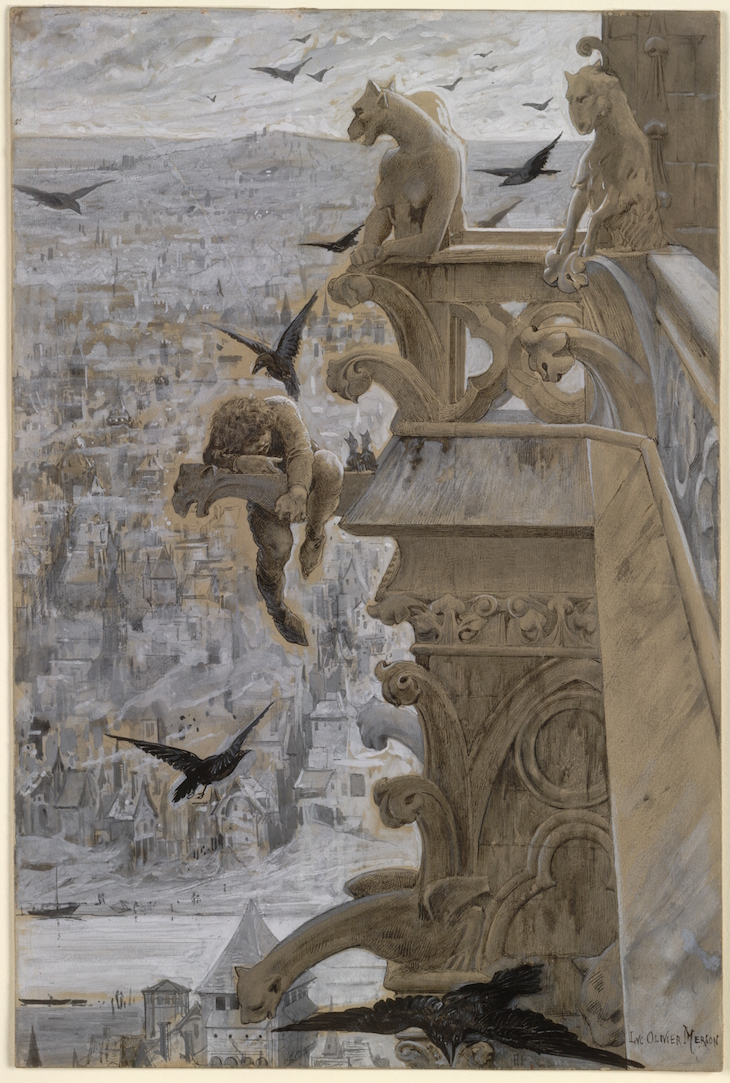

Notre-Dame de Paris (c. 1881), Luc-Olivier Merson. Cleveland Museum of Art

Sometimes one caught sight, upon a bell tower, of an enormous head and a bundle of disordered limbs swinging furiously at the end of a rope; it was Quasimodo ringing vespers or the Angelus. Often at night a hideous form was seen wandering along the frail balustrade of carved lacework, which crowns the towers and borders the circumference of the apse; again it was the hunchback of Notre-Dame. Then, said the women of the neighbourhood, the whole church took on something fantastic, supernatural, horrible; eyes and mouths were opened, here and there; one heard the dogs, the monsters, and the gargoyles of stone, which keep watch night and day, with outstretched neck and open jaws, around the monstrous cathedral, barking. And, if it was a Christmas Eve, while the great bell, which seemed to emit the death rattle, summoned the faithful to the midnight mass, such an air was spread over the sombre façade that one would have declared that the grand portal was devouring the throng, and that the rose window was watching it. And all this came from Quasimodo. Egypt would have taken him for the god of this temple; the Middle Ages believed him to be its demon: he was in fact its soul.

From The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), Victor Hugo

West Front of the Church of Notre Dame (1828), drawn by Augustus Pugin. engraved by James Tingle. Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

Notre-Dame (Abside) (1860s), Édouard Baldus. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Gothic of Verona is far nobler than that of Venice; and that of Florence nobler than that of Verona. For our own immediate purposes that of Notre-Dame of Paris is noblest of all; and the greatest service which can at present be rendered to architecture, is the careful delineation of the details of the cathedrals above named, by means of photography.

From The Seven Lamps of Architecture, preface to the second edition (1855), John Ruskin

Notre Dame, Paris. View of spire, roof with statuary, and cityscape beyond (c. 1860), Charles Marville. Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

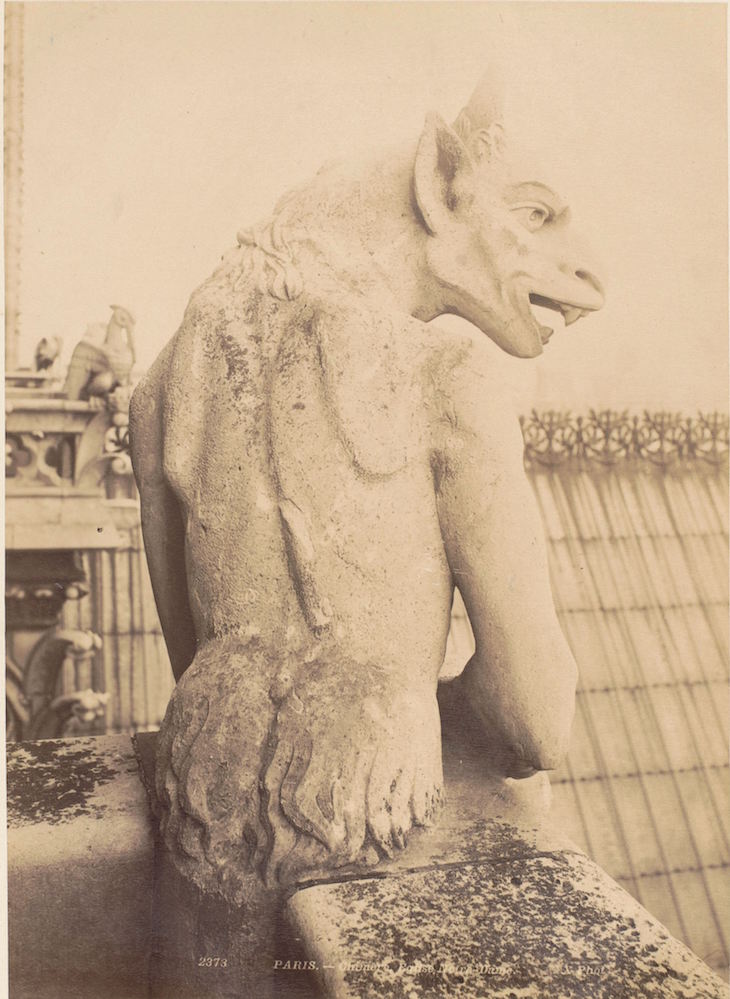

Sculpture of a gargoyle at Notre-Dame in Paris (c. 1875–1900), anonymous. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Fermer les yeux, ne peut ne voir, régentant la cité comme au temps défunt, l’accroupie en le dégagement mystérieux de ses ailes, ombre de Notre-Dame.

From ‘Magie’ (1897), Stéphane Mallarmé

The Pont Neuf (1849–50), Johan Barthold Jongkind. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Interior of the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris (c. 1880–1900), anonymous. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

It wasn’t the first time Strether had sat alone in the great dim church – still less was it the first of his giving himself up, so far as conditions permitted, to its beneficent action on his nerves. He had been to Notre Dame with Waymarsh, he had been there with Miss Gostrey, he had been there with Chad Newsome, and had found the place, even in company, such a refuge from the obsession of his problem that, with renewed pressure from that source, he had not unnaturally recurred to a remedy meeting the case, for the moment, so indirectly, no doubt, but so relievingly […]

He trod the long dim nave, sat in the splendid choir, paused before the cluttered chapels of the east end, and the mighty monument laid upon him its spell. He might have been a student under the charm of a museum – which was exactly what, in a foreign town, in the afternoon of life, he would have liked to be free to be. This form of sacrifice did at any rate for the occasion as well as another; it made him quite sufficiently understand how, within the precinct, for the real refugee, the things of the world could fall into abeyance. That was the cowardice, probably – to dodge them, to beg the question, not to deal with it in the hard outer light; but his own oblivions were too brief, too vain, to hurt any one but himself, and he had a vague and fanciful kindness for certain persons whom he met, figures of mystery and anxiety, and whom, with observation for his pastime, he ranked as those who were fleeing from justice. Justice was outside, in the hard light, and injustice too; but one was as absent as the other from the air of the long aisles and the brightness of the many altars.

From The Ambassadors (1903), Henry James

The Right Hand of God Protecting the Faithful against the Demons (c. 1452–60), Jean Fouquet. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

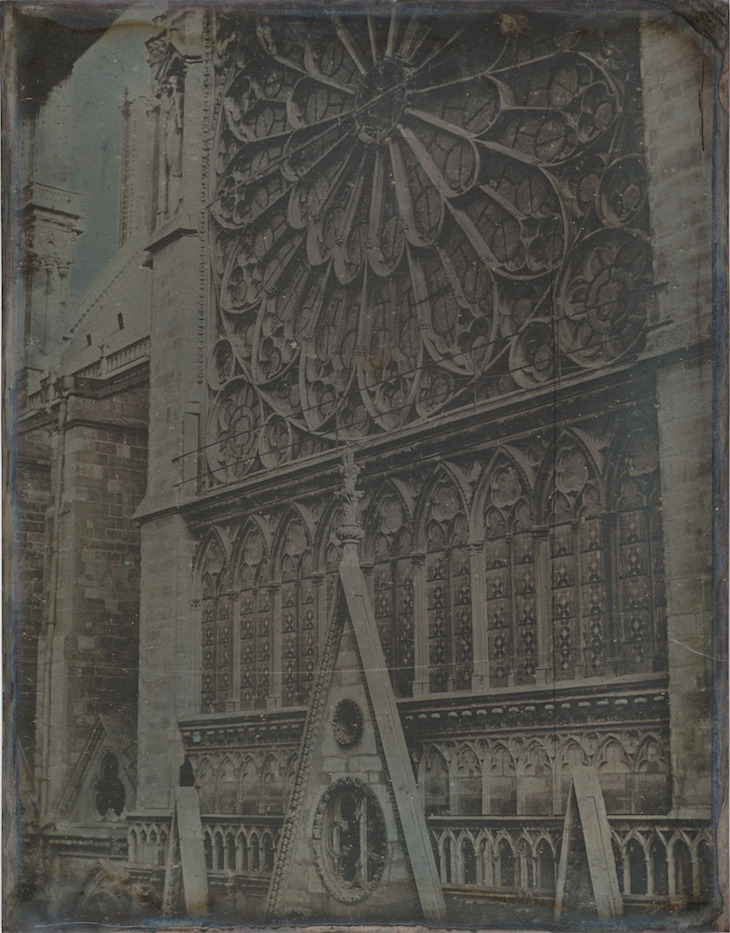

Notre Dame, Paris (1850s), Bisson Frères. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Lancettes, pendentifs, ogives, trèfles grêles

Où l’arabesque folle accroche ses dentelles

Et son orfèvrerie, ouvrée à grand travail ;

Pignons troués à jour, flèches déchiquetées,

Aiguilles de corbeaux et d’anges surmontées,

La cathédrale luit comme un bijou d’émail!

From ‘Notre-Dame’ (1838), Théophile Gautier

Notre Dame, Paris (1831–45), Thomas Shotter Boys. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

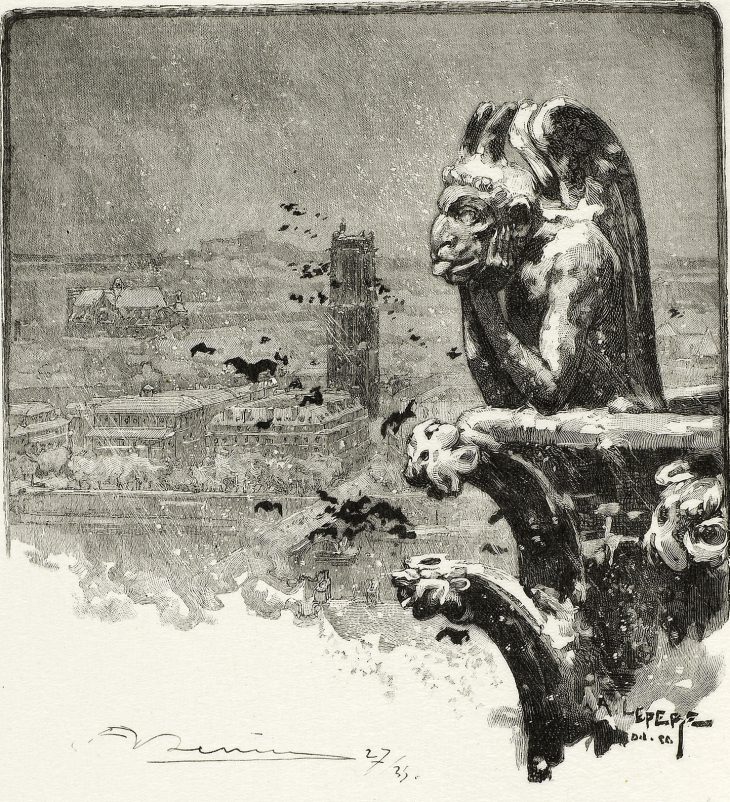

The Vampire of Notre-Dame, plate nine from Le Long de la Seine et des Boulevards (1890/1910), Louis Auguste Lepère, published by A. Desmoulins. Art Institute of Chicago

Camille remained a month without finding employment. He lived as little as possible in the shop, preferring to stroll about all day; and he found life so dreadfully dull with nothing to do, that he spoke of returning to Vernon. But he at length obtained a post in the administration of the Orleans Railway, where he earned 100 francs a month. His dream had become realised.

He set out in the morning at eight o’clock. Walking down the Rue Guenegaud, he found himself on the quays. Then, taking short steps with his hands in his pockets, he followed the Seine from the Institut to the Jardin des Plantes. This long journey which he performed twice daily, never wearied him. He watched the water running along, and he stopped to see the rafts of wood descending the river, pass by. He thought of nothing. Frequently he planted himself before Notre Dame, to contemplate the scaffolding surrounding the cathedral which was then undergoing repair. These huge pieces of timber amused him although he failed to understand why.

From Thérèse Raquin (1868), Émile Zola

Notre Dame, Paris (1839), Thomas Shotter Boys. Art Institute of Chicago

The Angel of the Resurrection on the Roof of Notre-Dame, Paris (1853), Charles Nègre.

Notre-Dame est bien vieille: on la verra peut-être

Enterrer cependant Paris qu’elle a vu naître ;

Mais, dans quelque mille ans, le Temps fera broncher

Comme un loup fait un boeuf, cette carcasse lourde,

Tordra ses nerfs de fer, et puis d’une dent sourde

Rongera tristement ses vieux os de rocher!

Bien des hommes, de tous les pays de la terre

Viendront, pour contempler cette ruine austère,

Rêveurs, et relisant le livre de Victor:

– Alors ils croiront voir la vieille basilique,

Toute ainsi qu’elle était, puissante et magnifique,

Se lever devant eux comme l’ombre d’un mort!

‘Notre-Dame de Paris’ (1832), Gérard de Nerval

Autre Vue Particulière de Paris depuis Nôtre Dame, Jusques au Pont de la Tournelle (1729), Jacques Rigaud. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Rose Window, Notre-Dame Cathedral, Paris (1841), Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

As one who, groping in a narrow stair,

Hath a strong sound of bells upon his ears,

Which, being at a distance off, appears

Quite close to him because of the pent air:

So with this France. She stumbles file and square

Darkling and without space for breath: each one

Who hears the thunder says: ‘It shall anon

Be in among her ranks to scatter her.’

This may be; and it may be that the storm

Is spent in rain upon the unscathed seas,

Or wasteth other countries ere it die:

Till she, – having climbed always through the swarm

Of darkness and of hurtling sound, – from these

Shall step forth on the light in a still sky.

‘The Staircase of Notre Dame, Paris’ (1849), Dante Gabriel Rossetti

View of Pont de la Tournelle and Notre Dame taken from the Arsenal (1802), Thomas Girtin and Frederick Christian Lewis the Elder. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

Sculpture of Virgin and Child, Notre Dame, Paris (1853–54), Auguste Mestral. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York