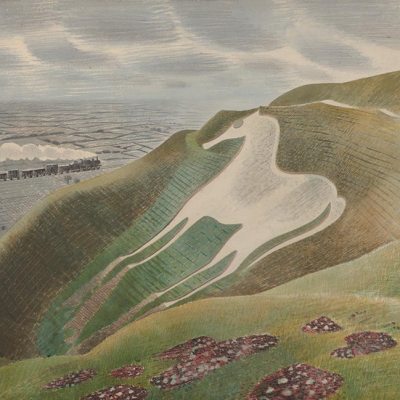

For many years Eric Ravilious was best known for his design work (commissioned by Wedgwood and London Transport), book illustrations, wood-engravings, and lithographs. Two years ago, an exhibition of his watercolour paintings at the Dulwich Picture Gallery revealed another side to his talents. Now, with the show ‘Ravilious and Co.: The Pattern of Friendship’ at the Towner Art Gallery (until 17 September), curator Andy Friend encourages us to see him firmly at the centre of a network of artists that included Peggy Angus, Edward Bawden, Helen Binyon, Barnett Freedman, Tirzah Garwood, Percy Horton, and Enid Marx. The book Friend has written to accompany the exhibition, beautifully produced by Thames & Hudson and including 239 illustrations, is the first comprehensive group biography of those loosely referred to as the ‘Great Bardfield Artists’ – after the Essex Village where many of them lived from the 1930s onwards.

The story begins in South Kensington in the mid 1920s, where, while teaching at the Royal College of Art, Paul Nash came across what he’d later describe as an ‘outbreak of talent’. His influence on the group was significant – Nash, Marx declared later in life, was ‘the magnet that drew us together’ – not only encouraging them in their work, but introducing them to potential clients; perhaps most notably via his exhibition ‘Room and Book’ at the Zwemmer Gallery in 1932, which aimed to promote English modernism in applied design. Friend carefully charts the progress of his subjects throughout these early years, maintaining a good balance between their stories, but it’s in Great Bardfield that the group really coalesces, and the sense of the book as a group biography – significantly more extensive than anything that’s come before – takes flight.

Tirzah Garwood and Eric Ravilious at work on the Morecambe murals, June 1933

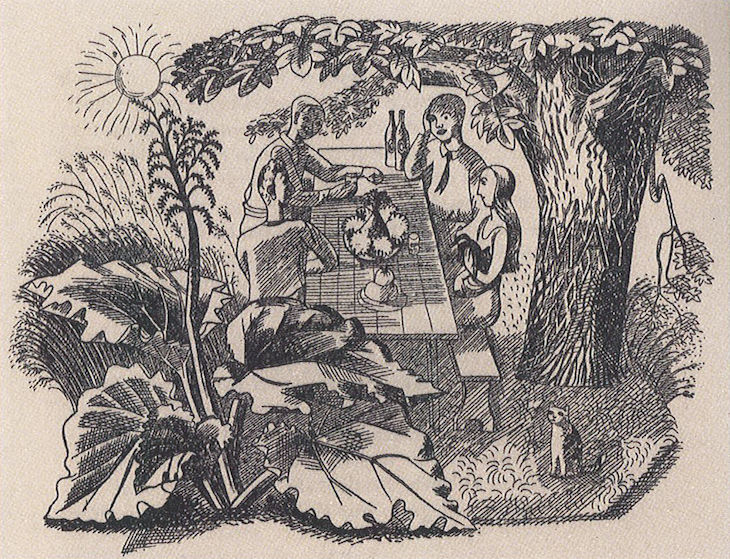

In the summer of 1931, Bawden and Ravilious (now married to Tirzah Garwood, whom he met while teaching at the Eastbourne School of Art where she was a student teamed up to rent half of Brick House in Great Bardfield. This, Friend explains, was ‘an inspiration for new work, village life a counterpoint to the London scene, and the house a significant crossroads in the evolving pattern of friendship’. As the house’s only long-term residents, Ravilious and Bawden’s relationship naturally takes centre stage. Previous collaborative projects – the Morley College murals which the two men completed in 1930, for example – gave way to them working alongside each other. Brick House was their ‘shared territory’ for two and a half years: ‘a period of comradely competitiveness and unselfconscious bohemianism that had yielded a rich artistic haul.’

This period of co-habitation has been previously documented, but Ravilious and Co. is a definitive effort to recognise it as the beginning of something akin to what the Bloomsbury Group had at Charleston – with whom, as Alan Powers reminds readers in his introduction, Nash had his own connection via Roger Fry’s Omega Workshop. Like the Pre-Raphaelites before them, he continues, both the Bloomsbury Set and the Great Bardfield Artists were noted for their ‘overlapping life stories’: ‘Friendship merged or sparked into love, often regardless of marriage ties, with predictable complications’ (Ravilious’s extramarital affairs included one with Binyon, and Garwood sought solace in the arms of John Aldridge). It’s a shame then that for all his excellently researched material, I never felt Friend got quite to the heart of the entanglements between his subjects. He diligently reports, but stops short of re-animating.

Illustration for May (showing Eric Ravilious, Edward Bawden and Tirzah Garwood in the Brick House garden), by Edward Bawden, published in Ambrose Heath’s Good Food, 1932. © Estate of Edward Bawden

Luckily we have Long Live Great Bardfield, Garwood’s own excellent autobiography to fall back on – edited by her and Ravilious’s daughter Ann Ullmann – and from which, it turns out, much of the best colour of Friend’s work is taken, including Garwood’s wonderful description of taking Ravilious home to meet her parents: ‘Eric seemed to recede into his clothes and sat in our chairs with the apprehensive expression of a shitting dog.’ He hailed from a class below the Garwoods, something that didn’t sit well with his future in-laws (ironically, Garwood’s rather unladylike simile undoubtedly would have appalled her parents). Not that this delineation was uncommon in the group. Friend, by means of correspondence between Binyon and Ravilious, points out that most of the women students at the RCA came from ‘good homes’ while the men were ‘seldom gentlemen by birth’.

Garwood’s style is charming, her clear and candid prose reminiscent of the loosely autobiographical novels of Barbara Comyns, an often overlooked mid-century writer and artist. She remains resolutely cheerful throughout, whether describing the delight she took in her work or the trials and tribulations of her and her husband’s affairs; and she paints captivating visual portraits, from Ravilious and co. to local village gossips. Friend provides us with a good sense of Garwood’s work – from her early woodcuts, through to her marbled paper work, to the singular paintings she produced towards the end of her life – one of which, The Springtime of Flight (1950), closes his book. Yet he seems to consider Long Live Great Bardfield, which he references often, more a source for information than an artistic achievement in its own right.

Tragically, both Ravilious and Garwood died young – he was 39 when, in the midst of his work as an official war artist, he was reported missing and presumed dead in Iceland in 1942; Garwood died of cancer nine years later at the age of 43 – but as both Ravilious and Co. and Long Live Great Bardfield show, they’d achieved much in their singular lives and, along with their contemporaries, are highly deserving of this belated attention.

Ravilious and Co. by Andy Friend is published by Thames & Hudson (£24.95); Long Live Great Bardfield by Ann Ullmann (ed.) is published by Persephone Books (£12).

The exhibition ‘Ravilious and Co.: The Pattern of Friendship’ is at the Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, until 17 September. It then tours to the Millennium Galleries, Sheffield (7 October 2017–7 January 2018), and Compton Verney, Warwickshire (17 March – 9 June 2018).

From the July/August 2017 issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.