Andor, which recently concluded on Disney Plus after two seasons, has united the critics: not only is it the best Star Wars drama in a long time, it is among the best television dramas in a long time. For the reader still unfamiliar with the show, created by Tony Gilroy, it covers the five years running up to George Lucas’s original Star Wars film, and depicts the fumbling coalescence of the rebellion against the Galactic Empire, just as that empire consolidates its power and stifles the last sources of legitimate opposition.

Much of the on-screen realism in Andor was generated through shrewd location shooting, rather than reliance on wall-to-wall CGI, and many of those locations are in London, so anyone who knows the city is rewarded with a rather fun tour of its modern architecture: the Barbican Centre, the Brunswick Centre, Canary Wharf and Terry Farrell’s Alban Gate tower all stand in for places on Coruscant, the imperial capital; the modernist West Wing of the Guildhall also makes a cameo in season two. Outside London, Santiago Calatrava’s astonishing City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia stands in for the Galactic Senate, somehow managing to out-sci-fi the CGI buildings in the background. As the forces of tyranny close in, the Calatrava becomes less of a backdrop and more of a protagonist in an episode of claustrophobic architectural intrigue. The dazzling Mediterranean sun doesn’t do anything to dispel the Gothic paranoia; in it, the ribbed science museum looks like the bleached skeleton of democracy.

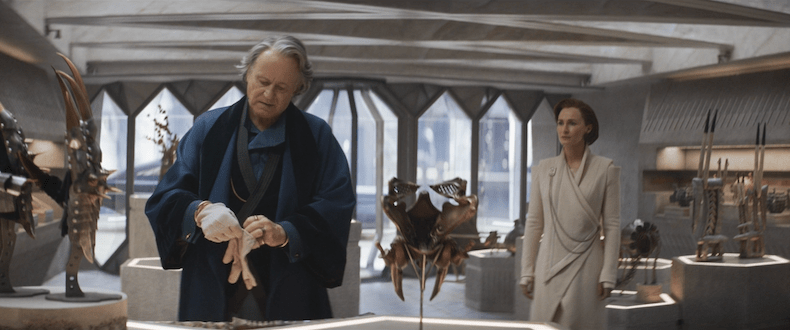

Architectural metaphors run through the heart of Andor – and so does art. Cassian Andor (Diego Luna), the eponymous focus of the show, is brought into the rebellion by the enigmatic Luthen Rael (Stellan Skarsgård). They are from different worlds, not just literally: Cassian is a rough-edged petty criminal from the backwoods, while Rael is – of all things – a dealer in antiquities. Rael’s showroom on the Coruscant equivalent of Pimlico Road, a purpose-built set by production designer Luke Hull, has display plinths of scored stone and a vaulted ceiling of what looks like marble cross-bracing, through which comes diffuse light of the sourceless kind John Soane called lumière mystérieuse. The antiquities on sale have been a treasure-hoard for Star Wars fans, containing dozens of ‘Easter Eggs’ connecting to different points of the universe’s voluminous lore – a head-dress of the sort worn by Natalie Portman in the prequel films, for instance. We might also see it as a gentle commentary on Gilroy’s work in Andor as a whole, creating a space for intrigue in between various bits of priceless, untouchable canonical inheritance, most of which stay safely in the background.

Stellan Skarsgård as antiquities dealer, spymaster and guerrilla leader Luthen Rael in his showroom with Genevieve O’Reilly’s Senator Mon Mothma in Andor. Lucasfilm Ltd.; © Disney

But the showroom, like its proprietor, has two sides – in the back, which is ostensibly a conservation workshop, Rael and his assistant Kleya Marki (Elizabeth Dulau) are running a resistance network through a clandestine communications system. The showroom is a front, but it’s not just a front. It appears to be a place of conspicuous consumption, where members of the imperial elite can soothe themselves with historical knick-knacks. Under this cover, the shop is regularly visited by senator Mon Mothma (Genevieve O’Reilly), who, behind a facade of well-meaning liberal impotence, is financing the rebellion through Rael’s network. ‘Free your mind, senator,’ Rael says warmly when she arrives complaining about the stresses of her senate work. ‘This is a place where time stands still. It’s hard being surrounded with this much history and not be humbled by the insignificance of our daily anxieties.’

This brings to mind Walter Benjamin’s description of the collector entering the ‘happiness of the solitary’, stilling the world and communing instead with objects, so that ‘even the people who haunt our thoughts then partake in this steadfast, confederate silence of things’; the collector is able to disappear into the world of memory.’ It’s a performance, though, put on for the benefit of Mothma’s driver, who is likely an imperial spy. As soon as they are out of earshot – in that back room – he switches to curt instructions and warnings. It’s a wonderful performance, which Skarsgård has compared to playing two entirely different characters.

But it wouldn’t work without the antiquities. Rael couldn’t be a boutique stationer or purveyor of fine smoked tauntaun meat, even if those businesses also attracted senators. More than once the show uses an ancient artwork as a playing piece in intrigue, as a wedding gift, or the hiding-place of a listening device. It’s tempting to make a case that antiquities, and the long memory they provide, are inherently subversive. Perhaps the humbling insignificance Rael refers to might also apply to the certainties of the new order. An antiques dealer is also a venue for incipient resistance in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, although that turns out to be a front of another kind.

But that won’t quite stand up in the plush respectability of Rael’s shop. Moreover, an antiquities emporium in the metropole is an impeccably imperial space. As architectural historian Tim Anstey writes in his recent book Things That Move, a placid, static setting for antiquities has within it the ghost of much movement and upheaval: ‘Vases had to be purchased, messages sent, ships chartered, admirals persuaded auctioneers primed, landscapes surveyed, and enemies foiled within the system of mechanics that made the architecture of the interior important.’ The trade in antiquities in the age of empires here on Earth has always had a tendency to follow upheaval, and we can imagine that is also the case in a galaxy far, far away.

This to-ing and fro-ing makes a convenient cover for Rael’s other interests and puts him in contact with the lowly and the powerful alike, but it also has affinities with his real work. As a spymaster and guerrilla leader, he is essentially a connoisseur, appraising individuals and groups, sniffing out fakes, placing bids on promising ventures. The skills overlap. John le Carré’s character Toby Esterhase becomes dodgy gallery owner ‘Signor Benati’ after (mostly) retiring from spycraft. He deals in forgeries and can spot other frauds. ‘You don’t buy photographs from Otto Leipzig, you don’t buy Degas from Signor Benati,’ he warns George Smiley.

The dealer and valuer naturally walks the boundary between certainty and uncertainty, where the risk and profit are found. Antiquities aren’t inherently respectable or subversive – they are helpfully ambiguous. When Mothma visits, the object that Rael tries to sell her is ‘a two-faced divinity’ – a sun goddess and a serpent, sharing the same mouth. A little on the nose perhaps, but fitting.

Andor is streaming on Disney+.