Architectural history is all too easily hijacked. Obsessive interest in a moment, a topic, a location or an individual often leads to myopic, ossified information. Nobody better represented the opposite approach to scholarship than Andrew Saint, who has died at the age of 78. For two substantial periods he edited the great Survey of London, a multi-volume, multi-format, multi-faceted history of the capital, setting the buildings within the city. Andrew was the architectural editor from 1974–86, then rejoined in 1995 when it was under the aegis of English Heritage. His mentor and model in the role of general editor, which Andrew assumed from 2006 until 2019, was Francis Sheppard, the very model of a public historian. When he died, at the age 96 in 2018, it was Andrew who wrote the Guardian obituary, a virtuoso piece of writing. Sheppard’s arrival at the office followed a pattern. He didn’t wait for the lift but would ‘bolt like a rabbit into his office and nestle between a fan of papers, hardly emerging before the next draft chapter had been completed for the typist in his beetling longhand.’ As it was in Andrew’s case, archival research involved ‘pinpoint-accurate notes’.

The breadth and range of Andrew’s interests were prodigious, allied to yet restrained by the exceptional acuity of his mind. A linguist who was able to conduct a doctoral viva in French, he was astonishingly well read, whether the original text and tongue be Horace’s or Cesare Pavese’s. He wrote with wit, economy and wisdom. It is almost impossible to capture fully his contributions to architectural, social and urban history – but through it all ran his love of Victorian architecture and loyalty to the group that protects and proselytises for it, the Victorian Society.

Educated at Christ’s Hospital and Balliol, Oxford, where he indulged his great love of and aptitude for music as a cellist in various trios and quartets, Andrew’s career was to be, essentially, that of a public historian. The exceptions were a brief period teaching art history at the University of Essex in the early 1970s and, later, as professor in the department of architecture at the University of Cambridge between 1995 and 2006. Latterly, he found himself leading the fight to avert the closure of the department (due to flawed research criteria). Supported by leading figures in the profession, the battle was fought and won but it was horribly debilitating.

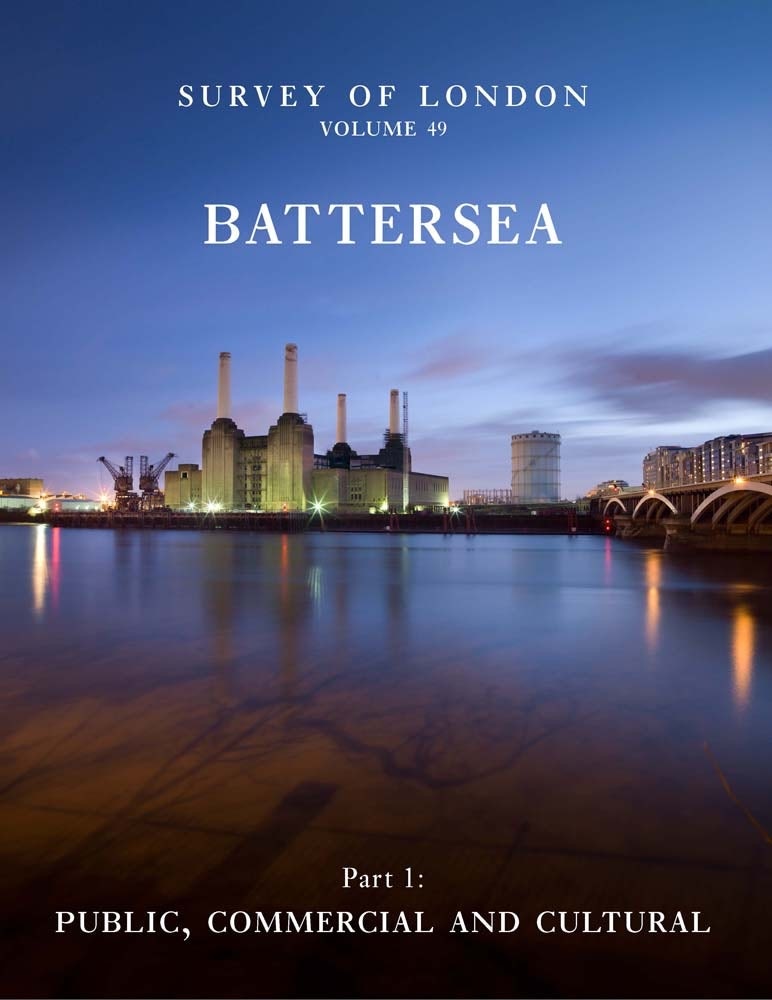

After he stepped down from the Survey of London, his writing about the capital showed no sign of slowing down. London 1870–1914: A City at its Zenith was published in 2021 and a lively broad-brush account of the parish of St Giles-in-the-Fields, written with Rebecca Preston, appeared in 2024. He took part in the London School of Architecture’s events in late March to mark 60 years since the GLC subsumed the LCC – he had edited Politics and the People of London: The London County Council 1889–1965. His last book, Waterloo Bridge and London River: Investigations and Reflections, will be published by Lund Humphries in November. For relaxation, he began writing fiction, sharing sections with friends. The first was set in the market gardens of Battersea.

For Andrew, Victorian and Edwardian architecture was not confined to these shores. He edited a series of publications for the Victorian Society of which French Architecture and the English 1830–1914 (2023)was the eighth. His introduction emphasised how the two-way nature of that topic was illustrated by a tiny development by an English speculator in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. Further afield, he supported the Society summer schools, run by Gavin Stamp, in the United States and the UK over decades. He was also involved with the British Architectural Library Trust, which seeks support from the United States.

One of Andrew’s endearing qualities was sharing his enthusiasms with friends. Among these was a near-missionary zeal for the qualities of London south of the Thames – to which he was himself a late-ish convert. On several crisp winter days during the second Covid lockdown, he introduced me to the landscapes and far vistas from Brockwell Park, Streatham Common (including the surprising hidden Rookery) and Norbury Park. Once, distanced against contagion by a municipal picnic bench, we downed a couple of midday whisky miniatures to mark our recent birthdays. London was in his veins, almost from the start. In 1960, his father, the Rev. Max (A.J.M.) Saint, became Chaplain at Guy’s Hospital where, decades later, Andrew had a kidney transplant and enjoyed telling the nurses about the connection.

When I first met him, without (then) even a master’s degree to my name, let alone a doctorate (like him, I now realise), he seemed intellectually austere but in the company of his then partner, Ellen Leopold, and their small daughters, Catherine and Lily, that impression shifted. Later the family returned to the United States without him. His third daughter, Leonora, was born in Strasbourg.

In the early 1990s Andrew asked me to help compile and edit a London anthology, The Chronicles of London (1994). Co-authorship is a test, but our friendship survived even if the pressures of our respective lives made us reluctant promoters, much to the publishers’ despair. Over the years we met for regular pub lunches, usually in central London but occasionally in Kennington in the south, for my continuing education. Even when terribly frail after treatment, he took pride in cooking for friends. We shared a memorable cake in his cottage in a tiny crescent on the Duchy of Cornwall estate.

Being in Andrew’s company always involved an exchange of recent reading, a dash of gossip and exasperation at yet another misstep by a familiar institution or bureaucracy (recently the displacing of the RIBA Library and Collections in the pursuit of a mirage, the House of Architecture). Given our shared delight in unconsidered trifles, the conversation took many unlikely turns. He wrote excellent postcards and loved spontaneous outings. When he and his long-term Dutch partner, Ida Jager, came to Essex I gave one such outing careful thought. Less an enthusiast for the Gothic Revival than he, I decided to head to Norton Mandeville, a hamlet where a tiny church and extensive Victorian model farm adjoin some intriguing farm cottages. Although they were undated and without an attribution, I hoped against hope to link them to Richard Norman Shaw, the subject of Andrew’s first book. Shaw was notably self-effacing, as Andrew wrote. Although the quality of the cottages is unmistakable, we settled on their being by Frederic Chancellor of Chelmsford. But who cares? We had fun.

For Andrew, learning, like exploring, was for sharing. He reciprocated fully, a listener who did not interrupt. As one respected mid-career historian wrote to me on hearing of his death, ‘He always went out of his way to say hello and seemed genuinely interested – a generous soul.’ For all his seniority, emphasised over the years by impressively bushy eyebrows rather than the acronyms of learned societies, his students and professional colleagues experienced that rare openness of spirit and mind. His views were wide and accommodating, even if his own interests were fixed upon the urban – above all in Victorian and Edwardian London. Few others could have taken on co-editing the 2004 history of St Paul’s Cathedral, the work of an often scratchy sack of experts, and emerged unscathed and still respected.

He was buffeted by the institutional changes of almost all the bodies in which he worked as a historian, beginning with the Greater London Council. Andrew’s intellectual hinterland was a defence. He could write a scintillating Diary for the London Review of Books on the grave of Ugo Foscolo in Chiswick, spiralling out to encapsulate the Romantic poet’s headstrong, disastrous journey from Florence, or submit an erudite and incisive review of Adrian Forty’s important book Words and Buildings.

Interest in and political sympathy for the post-war welfare state lay behind one of Andrew’s most widely admired books, Towards a Social Architecture: The Role of School Building in Post-War England (1987). He dedicated it to the memory of three architects ‘who believed in social purposes for their profession’. Centred on Hertfordshire County Council, this was an account of a briefly enlightened society and the patronage that it offered. But it is his contributions to the Survey of London that remain Andrew’s greatest achievement. He considered that his predecessor, Francis Sheppard, was ‘London’s greatest topographical writer since John Snow, the Elizabethan historian.’ That accolade must now be extended to him.

Gillian Darley is an architectural historian and a former president of the Twentieth Century Society.