Jean-Antoine Watteau was formally accepted to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1712. All he had to do to confirm the appointment was submit a painting. In the end, this task took him five years, a period punctuated by increasingly stern reminders from the Academy’s administrators. For some artists, such a delay might signal the slow germination of genius, but Watteau was probably just procrastinating. In the event, The Embarkation for Cythera (1717, now in the Louvre) was dashed off and handed in almost with the paint still wet. In the intervening period, he had been drawing. When he died in 1721 (from tuberculosis, at the age of just 37), Watteau left behind thousands of sheets of paper enlivened with lines in black, red and white – often all three colours at once, in the ‘trois crayons’ technique drawn from Netherlandish art.

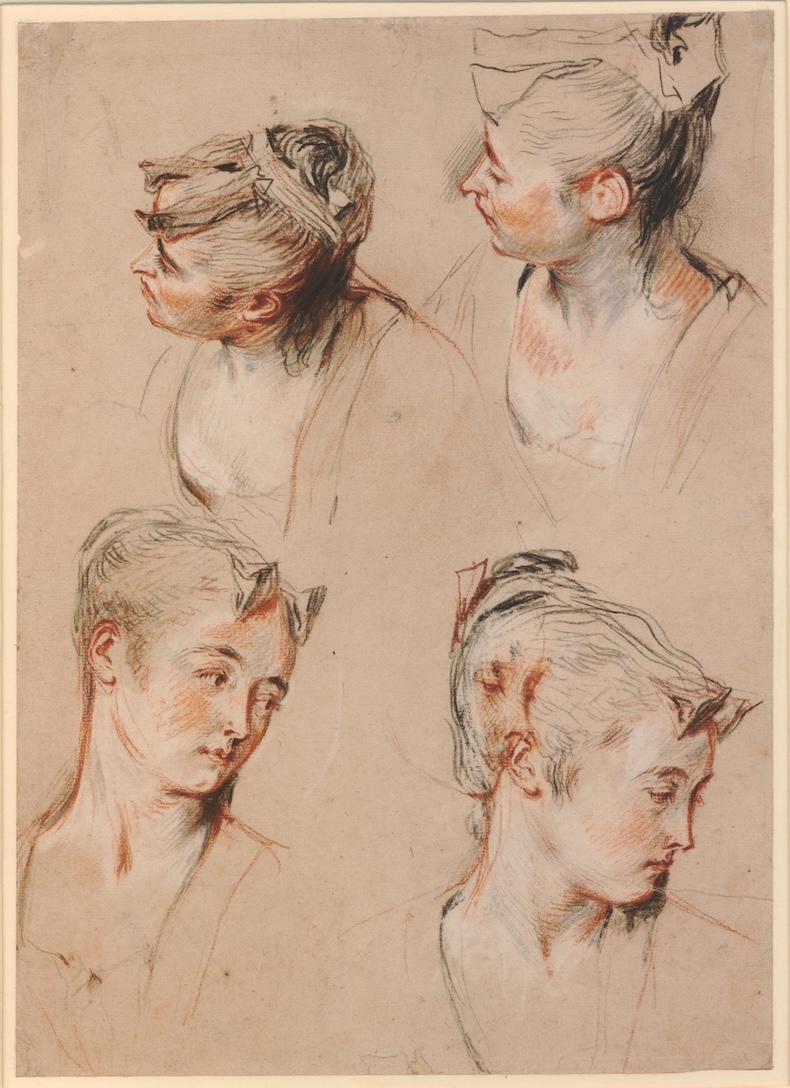

Four studies of a woman’s head (1716–17), Antoine Watteau. British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum, shared under a Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence

Many of Watteau’s loveliest drawings are currently on display in the Prints & Drawings Gallery at the British Museum. Earlier works, produced during Watteau’s return to his native Valenciennes in 1709, show long-limbed soldiers moving with elegant insouciance; a red-chalk soldier proffering a tray of army rations like a snuff box. Back in Paris, one of the ‘savoyardes’ who frequented the city during the barren winter months emerges from gritty lines of brown. She sits at an urban street-corner with the distinctive wooden box that was instantly recognisable to every Parisian child. Inside was a marmot, which could be brought out, for a price. Watteau was always drawn to details of costume, and the headscarf, cane and thick practical shoes of the ‘Savoyarde’ are rendered with the same care he brought to the costumes of the bon ton. Those images of the refined life are, for many, his most familiar and there are plenty of them here: a young lady sits on the grass in a ruff and riding cloak from the previous century; a guitarist picks out a tune with his long fingers and sheets of anonymous women turn their exquisitely rendered heads towards something we cannot see.

Seated figure of a woman’s head (1716–17), Antoine Watteau. British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum, shared under a Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence

In contrast to his dilatory approach to painting, Watteau seems to have drawn almost obsessively: his friend, the art dealer Edmé-François Gersaint, described how the pencil took up his every free moment. Even so, it is possible Watteau’s drawings are distinctive not so much for their number as for the pains he took to preserve them, at a time when many artists viewed their graphic oeuvre primarily as a step on the way to the greater goal of painting. Watteau’s drawings were certainly enmeshed with his painting practice. His sheets furnished many figures and motifs for canvas: the British Museum’s intent guitarist is resplendent in pink in The Scale of Love (c. 1717–18; National Gallery), but wears silver in the Gallant Recreation (c. 1717–20; Gemäldegalerie). At the same time, the ease with which Watteau isolated and extrapolated his figures gives many of his drawings an almost cinematic quality, which he never fully reproduced in paint. ‘Three Heads’ shows the same woman from three different angles, juxtaposed: we seem to be watching her turn away. Some of these effects were a long time in making. Years after drawing a standing servant with an apron, Watteau added a woman’s downcast head and shoulders, the pleats of her dress rhyming with the folds in the workaday linen; an artist in dialogue with his younger self. The endless return to earlier drawings makes Watteau’s work notoriously difficult to date, but also allows for frequent flashes of wit. One wonders what the abbé Haranger thought of his pencil portrait, made over an earlier nude study; a clerical collar juxtaposed with a buxom behind.

Two studies of man playing the guitar and a a study of a man’s right arm (c. 1716), Antoine Watteau. British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum, shared under a Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence

Though Watteau’s pride in his drawings was unusual, it was not unique. As the art market expanded in the early 18th century, many collectors were increasingly discovering graphic art. Drawings were often cheaper than paintings and could even be duplicated, via the counterproof. In an age that prized spontaneity, they also promised a more immediate insight into the artist’s working practice. At the beginning of his career, Watteau worked for a time at the house of the banker and collector Pierre Crozat, where drawings such as Francesco Zuccaro’s ‘Bearded Man’ must have been of interest not just for their use of the ‘trois crayons’ technique, but also for the respect Crozat accorded to them. Ultimately, respect for drawing was one of Watteau’s major legacies. After his death, in 1728, Jean de Jullienne published the lavish Figures de différents caractères, a two-volume celebration of Watteau’s drawings. Jullienne had Watteau’s work reproduced in lively etching, rather than the more stolid engraving, in a virtually unprecedented celebration of a contemporary artist’s graphic output. The project gave a start, and much inspiration, to up-and-coming artists including the young François Boucher, who produced some remarkable printmaking for the project. ‘Woman and Child’ deploys dots, dashes, swirls, and dense hatching, and is an extraordinary work in itself. However, no one could ever replicate the vivacity of Watteau’s original, in which the subject emerges, as if half-remembered, from an orderly chaos of red lines.

‘Colour and line: Watteau Drawings’ is at the British Museum, London, until 14 September.