From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The Renaissance architectural theorist Leon Battista Alberti thought it was not the business of architects to use drawings to deceive. Architectural drawings, he thought, ought to convey factual information as clearly and unambiguously as possible. Today, more than five centuries after the publication of Alberti’s De Re Aedificatoria, we continue to think of architects’ drawings in much the same way – as meticulous, if at times a little dry, repetitions of the formula of plan, section and elevation. A delightful new exhibition at Sir John Soane’s Museum in London (until 9 June) reminds us of how misconceived a view this is. Titled ‘Fanciful Figures’, its focus is on the small figures that can often be found in architectural drawings, both from the past and in the present, and provokes us to think about who they were and why they were included.

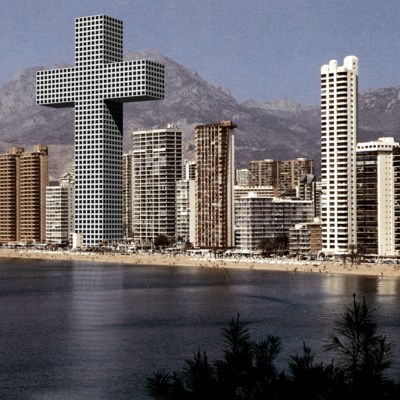

The technical name for these miniature figures and their accompanying dogs, hats and umbrellas, staffage, does much to indicate their origins. Deriving ultimately from the medieval Dutch word stofferen, meaning to fit out or to decorate, staffage was born of the world of Dutch landscape paintings, in which carefully observed groups of figures act as vignettes to give context and character to the wider scene. They first appeared in architectural drawings in the late 17th century, when perspectival views of architectural projects began to proliferate. These drawings were the forerunners of the modern architect’s perspectival rendering. Indeed, today the role of staffage has only continued to grow in importance, with architects increasingly seeking not only to give details of architectural construction in their drawings – now, of course, often made on a computer – but also, crucially, to give a sense of place.

RA lecture drawing by Henry Parke of Stonehenge (1817). Photo: © Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

The conventions of staffage were ultimately formed as the result of a dialogue between artists and architects. William Kent, who was trained in Rome as a figurative painter before he became an architect, embodies this fusion. Even his more formal studies in elevation and section can be peopled with charming and characterful figure studies. Kent’s figures may seem whimsical, but they have a seriousness of purpose that carries through to this day. Unlike other arts, architecture has to be designed with end users in mind. Today, an architect may include figures to give a sense of rooms in use. What better way to sell his or her design for a bathroom to a client than to include a sketch of a figure relaxing in a hot bath?

In the past, architects, whose skills were better suited to the painstaking processes of more conventional architectural drawing, would employ specialists to carry out their staffage. The transformative effect of these specialist hands can be startling. Joseph Michael Gandy, for instance, was supremely talented in the perspective renderings he made of some of Sir John Soane’s greatest projects, but clearly struggled when it came to figures. In a drawing he made of a dinner in one of Soane’s rooms in the Bank of England, Gandy’s liveried diners look like a row of wooden skittles. In drawings that have the input of Benedictus Antonio van Assen, by contrast, the figures are full of life and character. Van Assen was Soane’s favourite staffage artist. His lack of aptitude as a businessman is perhaps the reason that he is not better known. An intended publication dedicated to his drawings of figures from London life failed ever to be realised.

Why did architects include staffage, and why do they continue to do so today? At one level, the answer is simple – to give scale. Using staffage, an architect can easily convey to a patron, or prospective patron, who may not be trained in the conventions of architectural drawing, how a project would look if built in the real world. But the answer is not always so straightforward. If we look closely at Leonard Knyff’s c. 1695 drawing of one of Sir Christopher Wren’s schemes for Greenwich Hospital, for example, we see that many of the figures are comically out of scale and that the galleons in the drawing’s foreground are the same size as the rowing boats alongside them.

Royal Academy exhibition drawing by Joseph Michael Gandy with figures by Antonio Van Assen showing Pitzhanger Manor in Ealing (1801). Photo: © Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

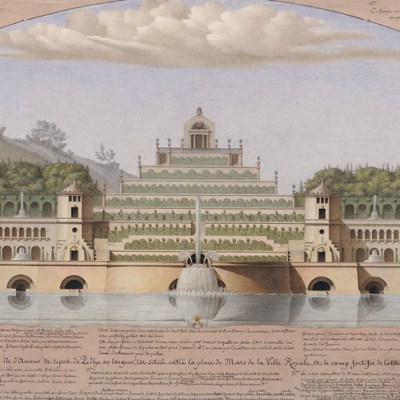

If they do not convey the building’s size, what purpose do these details serve? Here things become more nuanced. Knyff’s drawing of Greenwich is for a project that was never fully realised. The staffage here works alongside the exaggerated – and unrealistic – sense of perspective to beguile the viewer with vignettes that do not just give a sense of scale, but also make the building seem alive. It is no coincidence, then, that several of the most impressive drawings included in the Soane’s exhibition are for buildings that probably never could have been executed.

There is a more fundamental answer to this question, however, which is that staffage exists because buildings cannot exist without people. As such, historical examples of staffage give us a fascinating insight into who exactly architects imagined the end users of their buildings to be. Often, the results are predictable enough: well-to-do ladies and gents dressed in the most fashionable clothes of the day. But there are times when these figures hint at a society that was more heterogeneously composed. A drawing made by Gandy and van Assen for Soane, for instance, shows the Consoles Transfer Office of Soane’s Bank of England in use by figures who appear to be Jewish. Are these stereotypes or are they included to show the Bank of England as a great national project that encompassed all areas of society? The tension between these two possibilities is palpable.

In today’s world, architects think more carefully than ever about the issues raised by Gandy’s drawing. A video in the Soane exhibition shows present-day architects discussing how they people their project drawings and how carefully they consider community representation when introducing their staffage. Today, the question of who is at the forefront of architects’ minds. But the long history of staffage reminds us that, at its best, this is what architecture has always been about.

From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.