‘Whatever it grants to vision and whatever its manner,’ wrote Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida, ‘a photograph is always invisible.’ Perhaps this explains why there is very little writing about photographs of art collections, despite the fact that most if not all of us spend more time looking at images of artworks than at the objects themselves. This blind spot is no doubt due, in part, to the nature of photography: Susan Sontag observed that ‘a photograph – any photograph – seems to have a more innocent, and therefore more accurate, relation to visible reality than do other mimetic objects.’ But it is also due to the nature of art: works tend to become familiar and even famous through isolated images that separate them from the contexts in which they were, and are, encountered – be it in private houses or in public museums.

For a vivid glimpse of what we may be missing, we can consider the case of Louise and Walter Arensberg, best known as the pre-eminent patrons of Marcel Duchamp. The Arensbergs’ collection first took shape in their Manhattan apartment, soon after the Armory Show of 1913; and it expanded after their move to Los Angeles in 1921, gradually filling every available space in their house at 7065 Hillside Avenue in Hollywood. Until their deaths in the early 1950s (when the art collection was acquired by the Philadelphia Museum of Art), the Arensbergs put the European avant-garde, the English Renaissance and Mesoamerican civilisations into dialogue through dense arrays that shocked and inspired a stream of visitors. Celebrated both for the nature of the objects it held and for the manner in which they were displayed, the domestic museum created by the Arensbergs has been represented by a handful of images showing only a few rooms in the house.

For a vivid glimpse of what we may be missing, we can consider the case of Louise and Walter Arensberg, best known as the pre-eminent patrons of Marcel Duchamp. The Arensbergs’ collection first took shape in their Manhattan apartment, soon after the Armory Show of 1913; and it expanded after their move to Los Angeles in 1921, gradually filling every available space in their house at 7065 Hillside Avenue in Hollywood. Until their deaths in the early 1950s (when the art collection was acquired by the Philadelphia Museum of Art), the Arensbergs put the European avant-garde, the English Renaissance and Mesoamerican civilisations into dialogue through dense arrays that shocked and inspired a stream of visitors. Celebrated both for the nature of the objects it held and for the manner in which they were displayed, the domestic museum created by the Arensbergs has been represented by a handful of images showing only a few rooms in the house.

The Arensberg collection may at first glance seem an unlikely choice for a photographic object lesson since the couple’s own attitude toward the medium was, at best, conflicted. They were in close contact with some of the most esteemed photographers of the 20th century (including Alfred Stieglitz, Man Ray and Edward Weston), yet they displayed virtually nothing by them alongside their paintings and sculptures. And while the Arensbergs allowed their collection to be photographed for a variety of purposes (from inventory shots to magazine spreads), they always insisted on being left out of the frame.

Nonetheless, the sheer importance of the Arensbergs’ collection and the unexpected richness of its photographic record make it a perfect case study for exploring what we see when we look at photos of artworks in situ. When Floyd Faxon aimed his lens at the Arensbergs’ living room fireplace in 1951, he took in two Duchamps, two Picassos, three Braques, and four Brancusis, interspersed with works by De Chirico, Klee and Rousseau, a monolithic figure from Easter Island, Persian rugs of various shapes and sizes, and a dozen pre-Columbian carvings. Had Faxon carried out a full photographic survey of the remaining rooms, he would have registered no fewer than 19 works by Brancusi and more than 40 by Duchamp (including all three versions of his notorious Nude Descending a Staircase).

Photograph taken by Floyd Faxon in c. January 1951 of the living room, with views into the dining room through the north and south archways, of 7065 Hillside Avenue. Photo: courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives. Pictured: Constantin Brancusi, Prodigal Son (1914–15) and Three Penguins (1911–12): © Succession Brancusi – All rights reserved (ARS) 2020. Georges Braque, Still Life (Violin) (1913) and Still Life (with the Word VIN) (1912–13): © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Marcel Duchamp, The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (1912) and Yvonne and Magdeleine Torn in Tatters (1911): © Association Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2020. Paul Klee, Village Carnival (1926): © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Pablo Picasso, Old Woman (Woman with Gloves) (1901) and Head (1906): © 2020 Estate of Pablo Picasso/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A composite portrait of the Arensberg collection can, in fact, be recovered from the estates of various photographers, from the couple’s personal papers and from the archives of the institutions that now house their works. We have spent more than a decade gathering and interpreting these images, and have presented them in Hollywood Arensberg (written with Ellen Hoobler and published by the Getty Research Institute). The heart of the book is a room-by-room and object-by-object tour of the collection on display in the couple’s California home as it approached the form that was handed down to posterity.

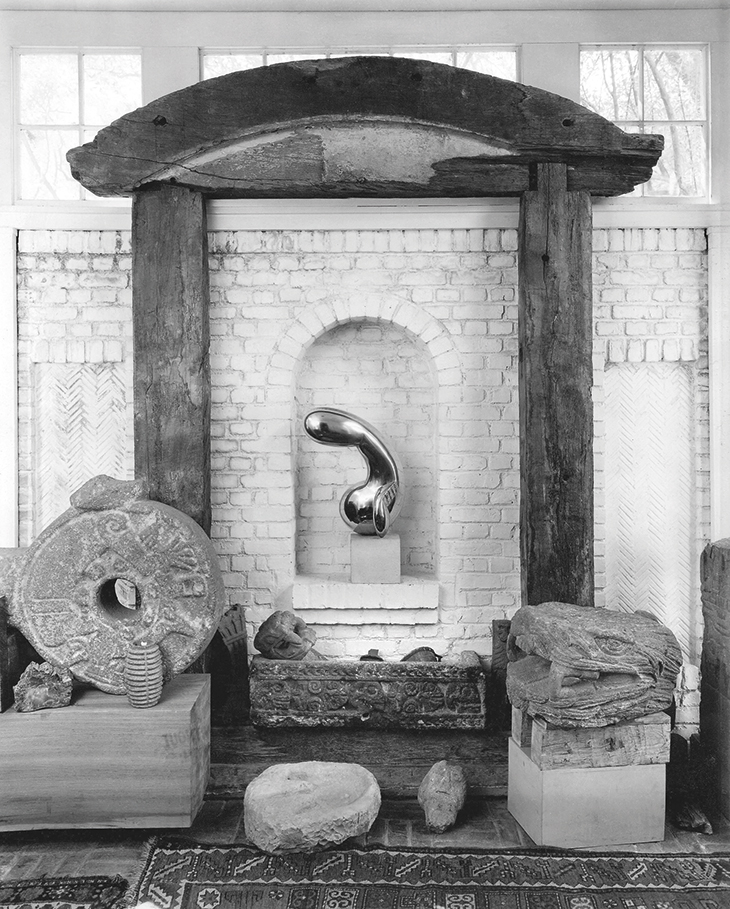

Such a survey runs the risk of fixing both objects and ensembles in space and time. When we have multiple pictures taken at different times, however, we can catch sight of a collection in motion, not only seeing individual pieces in different lights but better appreciating their changing relation to their surroundings. In revisiting the Arensbergs’ house, the natural starting point is the room where they welcomed their guests, the small, sun-filled foyer they commissioned from the architect Henry Palmer Sabin. Designed to hold two contrasting sculptures by Constantin Brancusi, the polished bronze Princess X and the large wooden Arch, it is among the first structures in the United States custom-built to hold specific pieces of modern art.

In the earliest surviving photograph of the foyer, taken in c. 1928 (quite possibly by the architect himself), we see only the two Brancusis displayed as planned. Photographs taken by Fred R. Dapprich and Floyd Faxon over the subsequent two decades show Princess X rotating within its niche and joined by an evolving tableau of pre-Columbian sculpture that included a Classic Veracruz palma, a Totonac head of a jaguar, and four striking Aztec works carved from volcanic granite – a basin, a ballcourt ring, a serpent’s head and a fragment of an upright slab showing the feet of a warrior or king. In the last-known image of the foyer, taken by Karl Bissinger in 1950 (for a never-published feature in Fleur Cowles’ Flair magazine), we can see that at some point the Arensbergs added two framed photographs into the mix. Picturing the archaeological sites of Tulum and Chichen Itza, these photos within a photo suggest that, much as we are doing today, the Arensbergs wrestled with contextualising the objects they owned and used photography to do so.

Photograph taken by Floyd Faxon in September or October 1948 of the foyer of Louise and Walter Arensberg’s house at 7065 Hillside Avenue, Los Angeles, designed by Henry Palmer Sabin to hold Arch (c. 1914–16) and Princess X (1915–16) by Constantin Brancusi. Photo: courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives; © Succession Brancusi – All rights reserved (ARS) 2020

These changing presentations of the foyer show the extent to which the Arensbergs (after their move to Los Angeles) gave pre-Columbian sculpture a place alongside their modern art: ‘Before our time,’ Walter claimed, ‘it was never recognized as art. Now it may outrank all other cultures.’ As a group, the sequence of pictures also begins to convey the special pleasure the Arensbergs took in reconfiguring their collection – even drawing their visitors into the action. One of their earliest and most frequent guests was Charis Wilson, an aspiring writer who would become Edward Weston’s second wife. In her memoir, Through Another Lens (1998), Wilson recalled a typical visit: ‘[Walter] would instantly consult me, perhaps about two pictures in the entryway. He’d thought of exchanging their positions. Would it be an improvement? Or were they better as they were?’ As they talked through the options, Walter dazzled her with explanations of the complex symbolism he found in the works: ‘My delight in his wordplay, puns, conundrums, and cryptic meanings behind cryptic meanings was so stimulating I felt buoyed up for days.’ Walter’s sway was understandable: he was after all, a professional poet who had hosted the salons where New York Dada was born, producing experimental poems between word games and chess matches with Marcel Duchamp; and he was an amateur scholar who had created the world’s largest private library about Sir Francis Bacon in his quest to prove that he was the secret author of Shakespeare’s plays.

Not everyone found Walter’s interpretations so convincing. Wilson’s future husband Weston engaged with the collector in a long-running debate about the presence of sexual symbols in his photos of natural forms. ‘For a long time,’ Wilson wrote, ‘I was secretly on Walter’s side of the argument […] My eyes would need a long re-education before I began to see Edward’s photographs as he saw them.’

Weston never photographed the Arensberg collection, but of those photographers who did it was Clarence John Laughlin who was most closely attuned to Walter’s symbolic mindset. Laughlin saw his images not as direct representations of reality but as poetic interpretations in their own right: he used every technique at his disposal to ‘give us a reality’ (as he put it in the prologue to his book Ghosts along the Mississippi [1948]) ‘where symbols have a life of their own’. Laughlin visited the Arensbergs in 1950 to make a ‘large group of experimental pictures’: focusing almost exclusively on the sculptures in the house, they involved dramatic lighting, extreme angles and even radical cutting of the finished prints. Not surprisingly, Brancusi featured prominently in the portfolio; and when the set was sent to the Arensbergs, the first item was the image Laughlin titled The Voracious Princess. As he explained in a characteristic caption,

This shows ‘The Princess’ installed in a special niche which the Arensbergs had built into the wall of their house. In this interpretation, the sculpture has eyes of shadow, and glittering teeth of light – while it has swallowed the whole room below.

He elaborated upon the effect in a separate description included with the shipping inventory:

The golden metal is like a congealed object of dark liquid, with the lower portion enclosing the room beyond (even the rug), while the curve in the top of the sculpture is echoed in the curve of the brick arch. To one side of the lower portion the light re-appears as though it had come to birth in the metal figure, and had been then re-born upon the wall.

Laughlin’s emphasis on Princess X as a symbol of rebirth may well mirror the intention of the owners: close examination of the sculpture’s reflective surface (through magnification of Laughlin’s print) reveals that the Arensbergs hung Brancusi’s Study for ‘The Newborn’ and Study for ‘The Princess’ on the opposite wall, flanking the door leading to the living room.

Crossing the threshold between Brancusi’s studies – perhaps the ‘two pictures in the entryway’ mentioned by Wilson – visitors faced the fireplace captured by Faxon, a view dominated by Duchamp’s The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (1912). Jostling for space with works by some of the 20th century’s most famous artists, Duchamp’s painting seemed (according to another contemporary visitor, the actress Helen Freeman Corle) ‘[to] overshadow and swallow them all up’.

Photograph taken by Karl Bissinger of the sunroom at 7065 Hillside Avenue on 16 March 1950, showing Marcel Duchamp’s first work on glass, Glider Containing a Water Mill in Neighboring Metals (1913–15). Photo: © Estate of Karl Bissinger; courtesy University of Delaware Library, Newark. Marcel Duchamp: © Association Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2020

Indeed, Duchamp had long commanded the attention of the Arensbergs and their guests. By the 1940s the living room held no fewer than seven works by the artist; and the adjacent sunroom (built on to the back of the house by Richard Neutra in 1933) added six more to the tally, including the glass piece Glider Containing a Water Mill in Neighboring Metals. Yet one of the earliest photographs of the Arensbergs’ house, taken by Beatrice Wood, presents a view strangely devoid of Duchamp. A close friend of both the artist and the Arensbergs, Wood followed the collectors to California in 1928 and likely took this picture of the living room’s south-west corner not long after Sabin had installed the foyer. Taken with a shallow depth of field that puts more emphasis on the furniture than the paintings, the photograph is nonetheless clear enough to show Georges Braque’s Still Life (1918) in an unremarkable wood frame, mounted flush against the bare walls of the recently purchased house. Comparing Wood’s photograph to one picturing the same wall taken in c. 1944 by Fred R. Dapprich, we can be forgiven for thinking the Arensbergs simply switched this painting for The Table (1918) by Braque as their collection exploded in breadth and scope. However, when we look closely at the top of the frame that holds this painting, we can catch another glimpse of the collection in motion: the couple had installed a swivelling metal bracket so that either side of what is in fact a double-sided canvas – with Still Life on the recto and The Table on the verso – could be shown easily. Though this display technique was not original to the Arensbergs – Gustave Moreau, for example, had commissioned stylised swivelling frames for his studio-museum in Paris at the turn of the 20th century – such a contraption would nonetheless have been highly unusual in a domestic setting. The photographer Dick Seyffert found it novel enough to include a close-up view among the nine pictures he took of the collection during a visit in 1945 or 1946.

Duchamp had built a similar swinging frame into his Glider, and may have been inspired by the way these two adjustable frames interacted with the Arensbergs’ home when constructing his Box in a Valise – which features miniature versions of his artworks hanging on hinged, collapsible walls. With the idea of making an ‘album’ that would contain ‘approximately all the things I have ever produced’, the artist travelled to Los Angeles in 1936 to reacquaint himself with both his patrons and his own works, neither of which he had seen in more than a decade. Over the course of a 16-day visit, the Arensbergs commissioned a local photographer, Sam Little, to take new images for Duchamp, and they allowed the artist to move freely around the house, taking notes on the colours and other details of his pieces. Though initiated through photographic research, the result was a box, as Duchamp later explained, in which ‘reproductions of those paintings that I loved so much […] would be mounted like in a small museum, a portable museum, so to speak’.

Photograph of the south-west corner of the living room at 7065 Hillside Avenue by Fred R. Dapprich in c. 1944. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives. Pictured: Giorgio de Chirico, The Soothsayer’s Recompense (1913): © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Marcel Duchamp, The King and Queen Traversed by Swift Nudes at High Speed (1912): © Association Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2020. Jean Metzinger, Landscape with Roofs (1914): © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Pablo Picasso, Female Nude (1910): © 2020 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

It is ironic, then, that an artist so frequently associated with the idea that the spectator completes a work of art had become the spectator of his own life’s work as presented by his collector-curators. And Duchamp’s Box may well have inspired the Arensbergs to become more interested in preserving and presenting their collection as a whole. It is perhaps no coincidence that the earliest systematic pictures of the house were taken around the time the Arensbergs received their copy of the Box in a Valise.

Duchamp’s ‘portable museum’ probably influenced, in turn, the ultimate disposition of the Arensbergs’ collection. Having seen, in miniature, how he could isolate his works from those of other artists, his boldest move may have been to project this effect at the largest scale in the galleries of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA). While most of the rooms designed for the display of the Arensbergs’ collection in 1954 continued to feature juxtapositions between different artists, periods and media, Duchamp saw to it that he and Brancusi would get their own galleries in the Museum. This monographic approach to permanent display, with its emphasis on the development of an individual artist, was at this time a relatively new phenomenon in the history of museums, and there were very few precedents when Duchamp set about showcasing his own work in Philadelphia. He may have been aware of the Museo Canova in Possagno, Italy, or the Thorvaldsen Museum in Copenhagen (both created in the 19th century); and he had undoubtedly visited the Musée National Gustave Moreau and Musée Rodin in Paris (both open by 1920).

Early photographs of the Arensberg galleries in Philadelphia show the ultimate effects of Duchamp’s auteurial endgame. Comparing Brancusi’s Arch and Princess X in what was then gallery 1685 of the PMA to their place in the Arensbergs’ home in Hollywood puts into stark contrast the different curatorial protocols and visual regimes of domestic and institutional displays; and setting this picture from 1954 alongside the earlier images brings into sharp focus the dimension of time that Roland Barthes helped us to see in even the stillest of photos. In Camera Lucida’s most enduring argument, the so-called punctum that gives some images their arresting power presents us with intimations of change, with forefigurings of the oblivion that awaits all things. In the book’s most famous passage, he sees in a picture of his mother as a girl a vision of ‘death in the future’: photographs, for Barthes, always show us something that ‘will have been’. But if photography of art collections can show us displays before they have died, it can also be used to bring them back to life.

Hollywood Arensberg: Avant-Garde Collecting in Midcentury L.A. by William H. Sherman, Mark Nelson and Ellen Hoobler is published by the Getty Research Institute.

From the October issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.