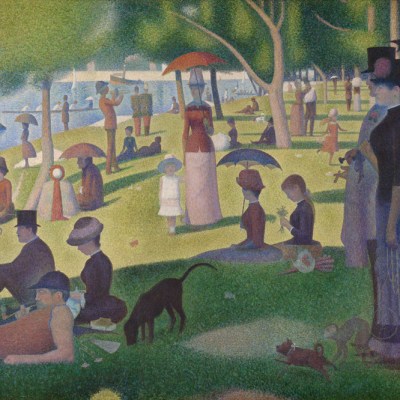

Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – 1884 (1884–86) is one of the most recognisable works of art there is. It has made appearances in The Simpsons, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and even in topiary at Topiary Park in Columbus, Ohio. So when Rakewell saw its most recent co-optation by pop culture it was less a case of shock than of curiosity. Photographed at the Art Institute of Chicago, fresh from their triumph in the Wicked franchise, were Ariana Grande and Jonathan Bailey, sitting in front of Seurat’s painting. The pair posted the photo on Instagram with the caption, ‘All it has to be is good’.

As every lover of musicals will know, the title of the second Wicked film is Wicked: For Good. Could this, Rakewell wondered, be yet another stage of the Wicked press tour – perhaps the closest a press tour has come to performance art? (Who can forget Grande and Cynthia Erivo’s themed clothing or the way they transformed our language with such phrases as ‘holding space’?)

But no: Rakewell was quietly relieved to see that the Instagram post was in honour of a very different musical – Stephen Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George. Apollo has discussed this play before, but now Rakewell is fascinated not so much by the meaning of the painting (or indeed the musical) as by what might happen when such cultural behemoths as Ari and J-Bay take it on. Bailey is no stranger to Sondheim: he appeared in the most recent West End production of Company, during which he very elegantly managed to sing from within both a kitchen cabinet and a refrigerator.

The production they are promoting is to take place at the Barbican in London, a marginally more European setting for Seurat’s Parisian scene than its current Chicagoan berth. Rakewell likes the idea that these two superstars took the time to go and look at the original, though the nature of their research does raise some questions. For example, there is an obvious formality to the figures in the work, heightened by the fact that they are all facing in the same direction. Sadly, Bailey and Grande are turned in their chairs to face each other, showing a remarkable disregard for the composition before them.

But Rakewell commends their research nonetheless, and hopes that in the intervening year and a half before the play arrives in London, we might see many more moments of dedication. Perhaps they could visit the banks of the Seine and try to recreate the painting, having changed their dress to suit a more 19th-century style. Rakewell would particularly like to see Bailey and Grande applying Seurat’s experiments with colour theory to their costumes – they could become human renditions of pointillism. And by next summer, Bailey might have had time to grow the masses of facial hair that Seurat was photographed sporting. In which case, Rakewell will be, as Grande almost sang, so into them we can barely breathe.