From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Are we living in ‘The Age of Influence’? This is the name of a recently released docuseries that looks at the dark side of influencer culture through the stories of six of the biggest social media scandals. The first episode features the art world’s own notorious influencer, Anna Delvey – real name Anna Sorokin – who pretended to be a German heiress to con Manhattan’s elite into funding her non-existent, members-only arts club. Through Instagram, Sorokin was able to perfectly project a lavish lifestyle that supported her fake persona.

This is a slightly different take on the usual understanding of ‘influencer’: a marketing term that officially entered the English dictionary in 2007 to describe ‘a person who has become well-known through use of the internet and social media, and uses celebrity to endorse, promote, or generate interest in specific products, brands, etc., often for payment.’

While the influence of celebrities and the power of their endorsements has existed for perhaps a century or more, social media influencers are a much more recent phenomenon that grew out of the stratospheric rise of social media platforms – such as Facebook, Instagram and Weibo in China – in the 2010s. Many influencers are famous not for a specific talent, but simply for sharing details of their everyday lives online. Brands send free products and host exclusive events for influencers in return for sharing social media posts to their dedicated followers. Brands are projected to spend $21.1bn on influencer marketing in 2023, more than triple the amount spent in 2019, according to the data firm Statista.

But do social media influencers exist in the art world? We can be certain that people are buying art directly from social media plat- forms. UBS and Arts Economics revealed in their Survey of Global Collecting in 2022 that 53 per cent of the 2,709 high-net-worth collectors responding had purchased works directly from an online or social media platform – 95 per cent had purchased works of art at some stage without viewing them in person first, with 51 per cent regularly doing so.

Leading galleries are alive to the importance of influencer culture: in 2018 David Zwirner hired Elena Soboleva, a social media expert with thousands of followers, to lead its online sales operation; and last year Pace took on Kimberly Drew, formerly the social media manager at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and who has 328,000 personal Instagram followers. But it seems unlikely that a blue-chip gallery would follow the traditional influencer route and send free works by leading artists to individuals on the direct promise of social media exposure (although it is hard to confirm this for certain – both Pace and David Zwirner did not respond to requests for comment).

‘I don’t think the art world considers itself in the same vein as fashion, beauty or other luxury products and therefore does not lean on influencers in the same way. So there hasn’t been such a slew of art world influencers,’ says Anna Seaman, the co-founder and curator of Morrow Collective, a curatorial platform for blockchain-based fine art. ‘The art world is much more closed than other spaces so the people who really have influence tend to go more under the radar.’

That being said, online platforms and art world players with large followings do hold sway on the market. ‘On anecdotal evidence, particularly from Asia, the role of social networks is extremely important,’ says art market journalist Georgina Adam. ‘The Chinese are so much on socials, they do everything with sites such as Weibo.’ Adam says that the popularity of the artists Giorgio Morandi and George Condo in China is because of the proliferation of their works on social media. ‘[The Chinese artist] Zeng Fanzhi bought Morandis and that certainly has had an influence [on Morandi’s popularity],’ Adam says.

‘The art market is the only major unregulated market where subjectivity reigns. It makes it prone to manipulation and influence,’ says creative director and brand strategist Vadim Grigoryan, who is currently writing a book on how luxury brands collaborate with artists. ‘When a famous collector, such as [billionaire French businessman] François-Henri Pinault buys several works by some artist, it automatically influences the quote for the artist.’

The people on social media, then, who have influence on the art market are in fact people who have what Grigoryan describes as ‘cultural capital’. Building on the work of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s book The Forms of Capital (1986), Grigoryan describes this as the amount of cultural goods and knowledge one has as compared to financial capital, which is the amount of money or liquefiable assets one has. He says that when these two forms of capital collide, the social clout reaches its peak (like in the cases of billionaires Pinault or Bernard Arnault, the owner of luxury conglomerate LVMH).

Since the art world is, as Seaman argues, more closed off than other industries, there are regular attempts to identify individuals of influence: ArtReview’s Power 100 does this annually, as does ArtNews’ Top 200 Collectors. These lists include individuals from all parts of the arts ecosystem: academics, curators, museum directors, gallery owners or sales directors, collectors, writers and, most importantly, artists. Another way of identifying influencers is just through the bald number of followers art world figures have on social platforms. The most-followed art world accounts on Instagram are those of artists. Street artists, who have mass appeal beyond the art world bubble, have the largest followings: Banksy has 12.1m, KAWS has 4.5m, and JR has 1.8m. Other popular artists on the platform include Takashi Murakami (2.5m), Damien Hirst (963,000), Ai Weiwei (683,000), Kehinde Wiley (602,000) and Jeff Koons (513,000). The blue chip galleries also have large followings: Gagosian has 1.5m, Pace has 1.1m, Hauser & Wirth has 834,000 and David Zwirner has 798,000. But as Grigoryan says: ‘There is always something inauthentic when an artist is highly praised by the gallerist that he or she is represented by.’

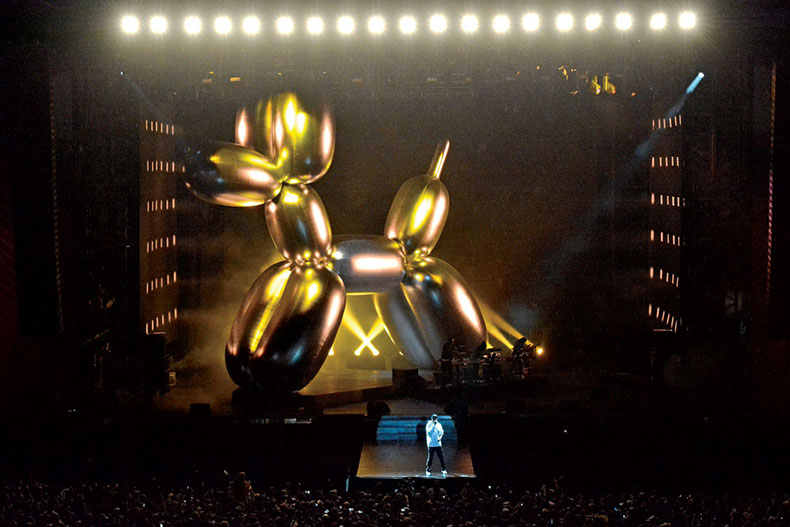

Jay-Z performs live on stage against a backdrop of a Jeff Koons sculpture at the V Festival at Hylands Park, Chelmsford, England on 20 August 2017. Photo: Jim Dyson/Getty Images

As in other industries, celebrities play a role in the art world: celebrity art collectors are often captured with their works; photographs of their homes reveal their tastes; and people eagerly discuss which famous faces bought what at art fairs and auctions. Recently, the story of a bidding war between socialite Kim Kardashian and American football star Tom Brady for a Condo work at a charity auction caught the art world’s imagination. (Brady won the picture but Condo, who was at the event, promised a commission worth $2m to Kardashian as a consolation prize.)

Do such associations have an effect on the art market? Adam believes their importance is huge. In early 2013, Jay-Z wrote the song Picasso Baby, in which he rapped about his longing to own a billion balloon sculptures by Jeff Koons. In November of that year, Koons’ Balloon Dog (Orange) sold at Christie’s in New York City for a record price of $58.4m. The two paired up in 2017 when Koons created a 40ft inflatable balloon dog for Jay-Z’s performance at England’s V Festival. ‘It must have had an influence, you see those balloon dog editions everywhere now,’ Adam says. The popularity of the balloon dog means you also see lots of rip offs of Koons’ design. This popular awareness of the work, which has now become iconic, may well feed into collectors’ desire to own the real work and thereby drives up prices.

The list of Jay-Z’s collaborations and references to artists is long and includes Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol, Damien Hirst and Mark Rothko. In 2021, Beyoncé and Jay-Z posed in front of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Equals Pi (1982) for a Tiffany & Co. advert that went viral online. That same year, Basquiat’s works sold for a record high of $439.6m, according to data gathered by Art Market Research for the Art Newspaper. In the same light, Kendrick Lamar’s current tour features several paintings by the Los Angeles-based artist Henry Taylor for the musician’s stage backdrops – could it be that by next year his market will have rocketed from this exposure?

A sculpture by Yayoi Kusama looms over Louis Vuitton’s Champs-Élysées store in Paris in January 2023. Photo: Frédéric Reglain/Alamy Stock Photo

Sotheby’s seems to be overtly aware of the power of celebrity influence: the auction house has had countless famous people ‘curate’ sales in recent years including musician Kelly Rowland, actor Robert Pattinson, the rapper Skepta, and the television host Oprah Winfrey. The most recent example saw the basketball player Kevin Love choose works for a sale in New York. While the celebrity curators may not necessarily lead to higher prices for objects in the sale, their star power increases awareness of the Sotheby’s brand and aims to bring in new audiences and collectors. The recent record-breaking Freddie Mercury sale at the auction house has shown how mere ownership of art by someone famous can add thousands of pounds to its value.

As is often the case in the art world, the cause and effect of trends is hard to pin down, but there seems to be a connection between people of influence, social media and art’s value. And we should expect to see a more traditional influencer dynamic growing in the industry as we witness increasing numbers of collaborations between artists and luxury brands, particularly in fashion. Yayoi Kusama partnered with Louis Vuitton earlier this year to create more than 400 polka dot-covered clothes and accessories and the marketing push was huge – the LV stores were covered inside and out with multi-coloured polka dots and animatronic Kusamas could be found in the shop windows. Many items were gifted to influencers and the resulting posts could be found all over social media. The world – and not just the art world – experienced a moment of Kusama mania. Though as Grigroyan says, ‘Kusama or KAWS become household names thanks to the brands with which they collaborate.’ So just who is influencing whom?

From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.