From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1949, the artist Robert Motherwell (1915–91) coined the phrase ‘New York School’. The term Abstract Expressionism seemed too narrow for the range of experimental painting emerging from his friends’ studios in Manhattan after the Second World War – a group of artists that included Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Lee Krasner, William Baziotes, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Richard Pousette-Dart, Clyfford Still and Philip Guston. It was also recognition that, steeped though these artists were in European Expressionist, cubist, Surrealist and abstract art, a movement radically new and distinctive was emerging. Peggy Guggenheim quickly saw the group’s significance after her arrival in New York in 1941, showing Pollock, Motherwell and Rothko in her gallery Art of the Century. Her pioneering shows of women artists – ‘Exhibition by 31 Women’ (1943) and ‘The Women’ (1945) – included Krasner, Perle Fine and Hedda Sterne, affiliates of the group.

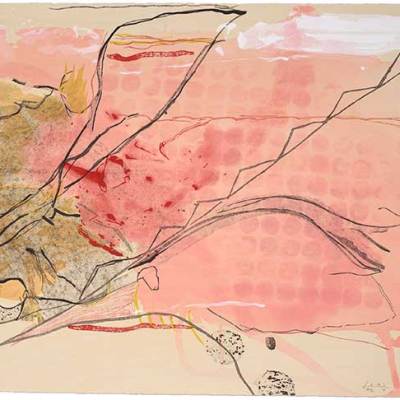

Initial shared interests in the subconscious and universal myth diversified in the 1950s into a focus on the idea of gesture in painting and the abstract colour field explorations of Rothko, Newman, Still, Ad Reinhardt and, later, Helen Frankenthaler. Huge scale added to the impact of these paintings. The group’s identity and cultural status were boosted by articles in Life magazine, by critics such as Clement Greenberg and by the momentous ‘9th Street Show’ in May and June 1951, curated by the Italian émigré Leo Castelli. Abstract Expressionism became a major force in the 1950s. Although 72 artists took part in that show – including 11 women, among them Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, Elaine de Kooning, Krasner and Frankenthaler – the school increasingly became identified with five or six names, the male AbEx superheroes: Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko, Newman, Kline and Still.

The Studio (1987), Robert Motherwell. Courtesy Bernard Jacobson Gallery

Prices for these artists rose with the art market, reaching stratospheric levels at auction in the 2010s. In 2011, Still’s 1949-A-No. 1 (1949), sold by his family to fund the Clyfford Still Museum, soared to $61.7m at Sotheby’s New York. In 2012 Rothko’s Orange, Red, Yellow (1961) achieved $86.9m at Christie’s New York. Six months later, Kline’s record leapt to $40.4m at Christie’s New York for a large untitled work from 1957. The sale at the same house in 2014 of Barnett Newman’s Black Fire I (1961) for $84.2m set another record. More recently, in November 2021, one of Pollock’s few canvases to come up for auction in recent years, Number 17 (1951), reached $61.2m (estimate $25–$35m) at Sotheby’s New York. The highest price has been achieved by Willem de Kooning, whose Interchange (1955) was sold by the David Geffen Foundation to Kenneth C. Griffin for a reported $300m in September 2015, making it the second most expensive work of art ever sold. Although prices largely have softened in the last five years, with much selling going on privately, Nicholas Maclean of New York and London dealership Eykyn Maclean remarks that a great example by any one of the big names ‘would hold its value’.

Elizabeth Webb, a specialist at Sotheby’s based in Manhattan, says, ‘Now more than ever, collectors take a broader view of this group, seeking opportunities among the best works of less well-known artists’ – that includes overlooked Black artists such as Harlem-born Norman Lewis, whose auction record rose to $2.8m at Sotheby’s New York in November 2019 for the intensely coloured Ritual, 1962 (estimate $700,000–$1m). But the big market story of the last few years has been the explosion of interest in women artists associated with the New York School. Museums led the way, with exhibitions such as ‘Women of Abstract Expressionism’ at the Denver Art Museum in 2016, the 2019 show ‘Lee Krasner: Living Colour’ at the Barbican in London, the Joan Mitchell retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2021, and the recent ‘Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940– 70’ at the Whitechapel in London, while the 2019 rehang of MoMA in New York exploded a dogmatic vision of what constituted the most significant art of any given year. Meanwhile, Mary Gabriel’s book Ninth Street Women (2018) offered sympathetic insight into the art and lives of Elaine de Kooning, Krasner, Mitchell, Frankenthaler and Hartigan.

Ritual (1962), Norman Lewis. Private collection. Courtesy Sotheby’s New York, $2.8m

Last November, two paintings by Mitchell achieved record prices. The early Untitled, painted in 1959, the year Mitchell moved permanently from New York to France, fetched $29.2m at Christie’s New York (estimate $25m–$35m), while a late colourful work, Sunflowers (1990–91), achieved $27.9m at Sotheby’s (estimate $20m–$30m). The international dealer David Zwirner, who works with the Joan Mitchell Foundation, emphasises that these works span her career. Rather than focusing narrowly on the classic New York School period – the ’50s and early ’60s – collectors are looking appreciatively at work by artists who continued to develop. Zwirner notes a turning point in May 2018 when Blueberry, a seven-foot-high canvas painted by Mitchell in France in 1969, fetched $16.6m at Christie’s New York, more than twice the $7m top estimate: ‘There is a new curiosity about this period. In the case of Mitchell it raises a lot of interesting questions about how an artist can innovate over decades.’

Gazelli Art House in London has also been catering to this sense of curiosity; its ‘9th St. Club’ exhibition in 2020 featured work by Elaine de Kooning, Frankenthaler, Hartigan, Krasner, Mitchell, Mercedes Matter and Perle Fine. From May to July this year, the gallery put on ‘Montage’, a show of collage by many of these artists. In 2022 it organised a retrospective of Fine, working with her estate. Sales director George Barker notes, ‘Throughout the decades she had different styles, though the 1950s Abstract Expressionist works, mostly in private hands, represent the peak of her market – £150,000 to £200,000.’

The New York dealer Edward Tyler Nahem points to ‘an uptick of interest’ in Hartigan, almost entirely for her 1950s work. In 2022, her Early November (1959) sold for $1.4m at Christie’s New York (estimate $800,000–$1.2m). Phillips will be offering the large, bold Montauk Highway (1957) in New York in May (estimate $800,000–$1.2m). The house has also seen climbing prices for Lynne Drexler, especially her breakthrough works from the late 1950s.

Montauk Highway (1957), Grace Hartigan. Courtesy Phillips, $800,000–$1.2m

The story is more complex for two other significant male artists, Philip Guston and Robert Motherwell. Guston’s turn from abstraction in the late 1960s confused collectors. Webb reports, however, that while ‘the top prices have been for the [abstract] early ’50s work, of which very little remains in private hands’, the last ten years ‘have seen recognition of different bodies of work,’ boosted by exhibitions at Hauser & Wirth and institutional shows in America and at the Royal Academy and Tate Modern in London. As for Motherwell, Bernard Jacobson, longterm dealer in his work and author of the book Robert Motherwell: The Making of an American Giant (2015), says he is ‘possibly the greatest American artist so far… He is a slow burn. You have to meet him halfway.’ With deep interests in European art and philosophy, Motherwell was a leading inspiration for Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s and ’50s. During the 2000s, Jacobson built his market in collaboration with the artist’s Dedalus Foundation. A peak was reached in 2018 with the sale at Phillips New York of At Five in the Afternoon (1971). A late recreation of the first in Motherwell’s sought-after ‘Elegy to the Spanish Republic’ series, it sold on estimate for $12.7m. Jacobson confirms that the ‘Elegies’ remain in demand, alongside his Open series (1967–69), and notes the importance of Motherwell’s collages. But he admits that today, with the focus on women artists, the market for Motherwell is pretty flat: ‘I am even thinking of becoming a buyer again!’

From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.