From the June 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In April the National Gallery in London announced the acquisition of its first painting by the Impressionist Eva Gonzalès – La Psyché (The Full-Length Mirror) (c. 1869–70), bought from a private UK collection for a tax-advantageous £1.5m. The purchase of this early work by the artist, a compelling painting of a woman looking at herself in a mirror, is a timely sequel to the gallery’s focus last year on Manet’s portrait of Gonzalès, who was his only pupil. It brings the number of paintings by women in the gallery to just 21, including two by Gonzalès’s contemporary Berthe Morisot, but allows the National Gallery in its 200th anniversary year to represent more fully the character and impact of Impressionism, this year celebrating its 150th birthday.

Morisot, who married Manet’s brother Eugène in 1874, was a founding member of the Impressionists. She hosted meetings of the group, including Monet, Renoir, Degas, Pissarro and Sisley, in her family home before their first exhibition in 1874, and exhibited in seven of the eight Impressionist shows. Gonzalès, by contrast, stayed aloof from the renegades, exhibiting only at the official Salon. Nevertheless, both were contributors to the radical transformations in subject matter, method and style that marked this moment in European art. Alongside the American Mary Cassatt, a close friend of Degas, and Marie Bracquemond, these women were acknowledged by their male peers as professional equals. Cassatt and Morisot in particular were promoted by the great dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, alongside Monet, Sisley, Pissarro and Renoir. Cassatt, as a socially well-connected art adviser, was instrumental in enabling American collectors and museums to buy the work of pioneering artists – including herself – while it was still new.

La Psyché (The Full-Length Mirror) (c. 1869–70, Eva Gonzalès. National Gallery, London. Sold for £1.5m

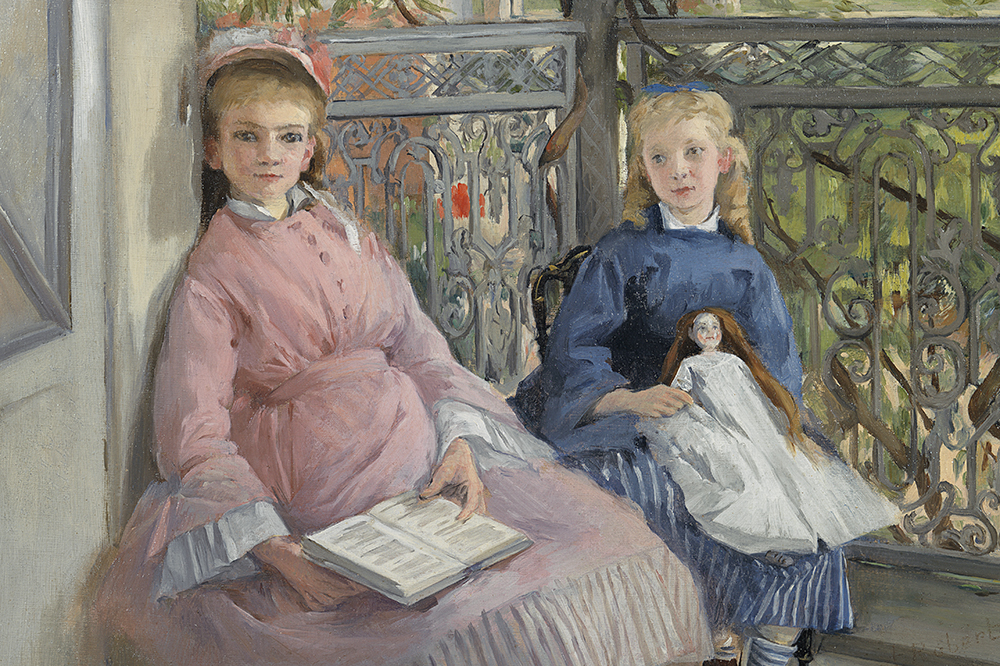

These women artists secured their place in the canon early on and have never been entirely lost to view – they were sought after in the 1980s and ’90s, at the height of the Impressionist market. But in the last decade, as institutional attention has turned to previously marginalised artists, their status and prices have begun to rise. Jonathan Green of London-based gallery Richard Green – Fine Paintings recognises this impetus in, for instance, Denver Art Museum’s purchase from them in 2017 of Gonzalès’s charming double portrait The Window (La Fenêtre) (c. 1865–70).

He suggests that the market has been stimulated by exhibitions such as ‘Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist’, which toured Quebec, Dallas and the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia before landing at the Musée d’Orsay in 2019; ‘Mary Cassatt: An American Impressionist in Paris’, which showed at the Musée Jacquemart-André, in 2018, and Dulwich Picture Gallery’s ‘Berthe Morisot: Shaping Impressionism’, which opened last year in London, and recently closed at the Musée Marmottan Monet. ‘They got consciousness going and brought things out of the woodwork,’ Green says. This month, ‘Women Impressionists’ opens at the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, after showing at Ordrupgaard in Denmark, while ‘Mary Cassatt at Work’ opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in May. Green notes that Cassatt’s market may recently have softened, but Morisot’s is strong. The chief problem, he thinks, is lack of supply.

Jeune fille étendue (1893), Berthe Morisot. Private collection. Richard Green, London

Thomas Boyd-Bowman, head of Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sales, Sotheby’s London, agrees. ‘While there has been a lot of talk about more interest in these artists, there has not been a flood on the market. Many of the best pictures are in institutions.’ Gonzalès died young, in childbirth; Bracquemond gave up in 1890, demoralised by the disparagement of her painter husband Félix; and Morisot died at the relatively early age of 54, of pneumonia caught while nursing her daughter. It was to avoid such obstructions that Cassatt never married – which, ironically, freed her to focus with enormous sensitivity on the subject of mother and child, constantly developing her technique in oils, pastels and etching.

Boyd-Bowman says that the best pictures have always been valued highly, pointing out that the painting that holds the current auction record for a Morisot – the bold, dynamic oil Après le déjeuner (1881), which in 2013 fetched £7m at Christie’s London (against a £1.5m–£2.5m estimate) – also broke records when it sold for $3.2m at Christie’s New York in 1997. ‘It has everything you want – scale, colour, dramatic brushwork, appealing subject matter,’ Boyd-Bowman says. He also notes that as the focus of collectors’ interest in the Impressionists has shifted to more experimental, less conventional late works by Monet and Pissarro, so earlier, more generic scenes have lost favour; that has given an advantage to Morisot, whose work developed significantly over time. He acknowledges that as understanding has grown of the women artists’ perspective on their female-centric subject matter, collectors recognise that ‘if you want a complete picture of Impressionism, you need these works.’ The quality bar, he observes, is higher for women artists than for their male peers – a name is not enough – and collectors lean towards highly characteristic works featuring women in interiors or gardens, or women and children.

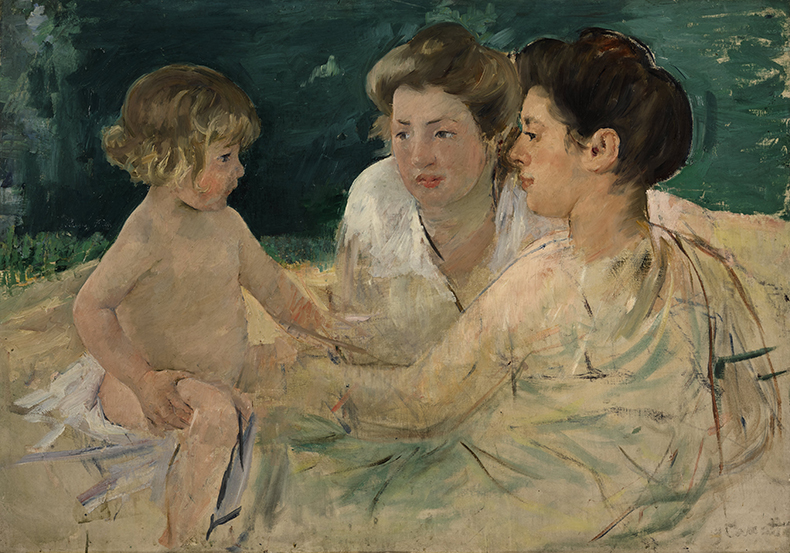

The Sun Bath, with Three Figures (1898–99), Mary Cassatt. Sotheby’s New York, $4.4m

Michelle McMullan, a senior specialist at Christie’s London, confirms this view, noting that the second-highest price for a Morisot was achieved for her quintessentially colourful, half-length figure painting Girl Carrying a Basket (1888), which sold at Christie’s New York in 2021 for $5.3m (estimate $2m–$3m). An exception might be the striking Cassatt Young Lady in a Loge Gazing to Right (1878–79), which sold at Christie’s New York in October 2022 for the auction record $7.5m (estimate $3m–$5m). Her best-known pictures are of women with children – such as The Sun-Bath, with Three Figures (1898–99), which sold at Sotheby’s New York in October 2020 for $4.4m (estimate $2.5m–$3.5m) – but this is one of a pivotal series of nine works focused on the audience in a theatre. Using pastel, gouache, watercolour and charcoal with metallic paint on paper, Cassatt creates a highly decorative, definitively modern image exploring the interior experience of a young woman in a public space. From the Ann and Gordon Getty Collection, it was bought by the Pola Museum of Art in Hakone, emphasising the global nature of her market today and renewed Japanese interest in this area. ‘Ten years ago, a work on paper by Cassatt would not have made this much,’ McMullan says. A light, sensitive pastel by Gonzalès from 1879, La Mariée (Jeanne Gonzalès), sold in New York in May 2020 for $100,000, four times the low estimate.

Emma Ward of the London dealership Ward Moretti reports that on the private market ‘Generally collectors are looking for fully resolved paintings or pastels, rather than the sketchier studies. A pretty, charming and engaging subject is preferred.’ She notes that while there is still a big discrepancy in price between male and female Impressionists, there has been ‘a marked uptick in demand for Morisot and Gonzalès’. It is hard to measure Bracquemond’s market, since the art market database Artprice lists only 52 lots at auction since the late 1980s, but a rare sale of works by Marie and her husband from their heirs at Artcurial on 30 April fetched prices well in excess of estimates.

The Window (La Fenêtre) (c. 1865–70), Eva Gonzalès. Denver Art Museum. Courtesy Richard Green, London

In its anniversary exhibition ‘Celebrating 150 years of Impressionism’ (until 29 June), the London-based Stern Pissarro Gallery will offer a graceful watercolour by Morisot, Jeune fille au repos (1894). It has recently sold an atmospheric oil painting by Blanche Hoschedé Monet, Paysage de neige (1910), to the Normandy museum renamed this year in her honour. She was both the step-daughter and daughter-in-law of Claude Monet. The gallery’s co-owner David Stern says, ‘We do now recognise these artists as part of the story. There are private collectors and museums wanting to fill this particular gap.’

From the June 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.