If you happened to be changing between the Northern and Jubilee lines at Waterloo station some time from 14 to 25 July, you may have noticed some unusual sounds rising above the usual ambient din of the London Underground: soft synths, a scatter of spoken voices, the hum of a choir in the distance, a series of whistling noises. This was Go Find Miracles (2025), a 10-minute work of sound art by the British artist Rory Pilgrim. It was commissioned by Art on the Underground, an organisation that almost all the roughly two million people who use the Tube each day will come into contact with at some point, in some way – even if most of them aren’t aware of it.

Art on the Underground is made up of a team of curators, managers and producers that sits within the wider scope of Transport for London (TfL) and is dedicated to making the Tube a more visually – or, in some cases, sonically – stimulating place. Pilgrim’s work is one of four major commissions taking place this year to mark the 25th anniversary of the project; all of this year’s programming is, as Eleanor Pinfield, director of Art on the Underground, tells me over Zoom, about creating ‘a moment of interaction for the public’ through which they become engaged with their environment – ‘the physical architecture of it; the psychology of the place’.

Because the body’s core funding comes from TfL, mixed in with some corporate sponsorship and various public grants, there is ‘a big onus on us’, Pinfield says, to make the case for the value of art in public space. Another of this year’s commissions, a piece by the Kurdish artist Ahmet Öğüt called Saved by a Whale’s Tail, provides a very literal interpretation of the usefulness of art. It takes the form of a public call for people to send in stories about how art has saved their life; the responses will form the basis of an artwork that will go on show at Stratford station in September. Öğüt’s starting point is the story about a train in Rotterdam that crashed through its barriers in November 2020 but was saved from falling into the water below by a fortuitously placed whale sculpture. ‘As a visual advert for what we’re talking about’, Pinfield says, ‘it’s quite hard to beat.’

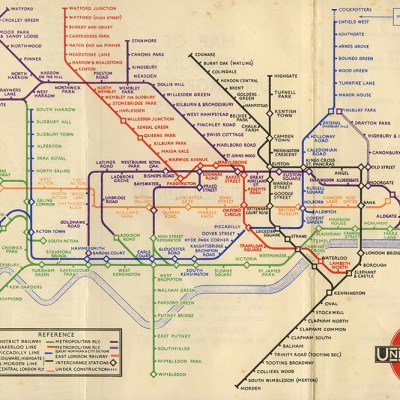

The London Underground has always had a strong line in design. Art on the Underground may be only 25 years old but its spiritual roots lie in the visual innovations of the 20th century, such as the sans serif font designed for the Underground by Edward Johnston in 1913, the sleek Tube map that Harry Beck developed throughout the 1930s and beyond – a version of which is still in use today – and the charming murals installed at every Victoria Line station when it opened in the late ’60s. In 2000, it was decided that a more official body was needed, so Platform for Art was established, a small-scale operation which commissioned temporary artworks to be displayed on Gloucester Road station’s disused Platform 4. In 2007 the programme was rebranded as Art on the Underground and Pinfield joined as director in 2014, coming from a job at the Tate, where she had worked on, among other things, developing and commissioning for the Tanks at Tate Modern – a role that, she says, prepared her well for working with art in ‘unexpected places’.

Some of these places are less unexpected than others: Underground users will probably all recognise the little mazes that you see on walls and platforms at various stations – 270 of them, all produced by the artist Mark Wallinger as part of his Labyrinth series in 2013. Travellers to and from Brixton station will know that a huge slab of wall above you as you enter the station has been given over to artists to display mostly figurative murals since 2018, including a domestic scene by Njideka Akunyili Crosby (2018–19), Denzil Forrester’s Brixton Blue (2019–21), which meditates on police brutality, and Claudette Johnson’s Three Women, which went up at the station last year. Gloucester Road’s disused platform is a little more out the way, but it has been the backbone of Art on the Underground’s commissions over the years. In 2003 Cindy Sherman lined the platform wall with 10 large-scale photographs of herself in various guises. Pinfield sees a more recent commission as one of her proudest moments: the cartoonish Heather Phillipson installation at Gloucester Road, my name is lettie eggsyrub (2018), which involved oversized eggs and other objects hung along the platform.

The limitations within which Art on the Underground must work can be incredibly difficult, Pinfield says. TfL’s overriding priority is, of course, to make sure it is running a ‘safe, reliable system’, so the artworks have to fit in around that. That means that the lead time for projects is often long – seven years on and off, for instance, for Alexandre da Cunha’s kinetic sculpture Sunset, Sunrise, Sunset, which was installed at the newly opened Tube station at Battersea Power Station in 2021. It also means that Pinfield and her team tend to approach artists with a specific space in mind. One exception to that was a commission from last year of a work by the duo Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings. ‘We went to them with some ideas and they brilliantly came back and said, “Actually, we’d really like to do something in a central London location, by a park.”’ This was a huge challenge, Pinfield says, since most of these central stations are cramped and have strict boundaries around what can be done with the space. That Pinfield and her team managed to negotiate a space at St James’s Park station – the only Grade I listed Tube station in London – and install a permanent mosaic by the artists she regards as a great coup.

There is another, more existential challenge in commissioning art for the Underground. TfL has a huge audience of potential viewers but, of course, the vast majority of people are not there to look at art. ‘You’re competing with so much visual noise,’ Pinfield says, but ‘we spend lots of time thinking about the site and the moment of interaction, so we can allow people that little bit of space.’ There are various strategies for this: artworks have been put up alongside escalators, for example, to give travellers something to look at in an idle moment. Pinfield is ‘very aware that some people will not engage’, but in some ways the incidental nature of the public’s interaction with these commissions is liberating, since, as she puts it, ‘You’re not being told to do anything; you can engage with it or you can not engage with it’. Art on the Underground is just one of the many things – Pinfield cites the busking scheme and the Poems on the Underground initiative too – that ‘give TfL its identity’, that lift travellers out of the drudgery of commuting and allow them to ‘engage with their space in a different way’ – even if it’s just for a fleeting moment.

For more information about Art on the Underground’s 25th anniversary programme, visit their website.