From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Giovanni Antonio Canal’s paintings are immediately recognisable but rarely set pulses racing. That changed this summer, when a ‘Canaletto’ from the 1730s, Venice, the Return of the Bucintoro on Ascension Day, sold at Christie’s London for a record £31.9m. It once belonged to Robert Walpole and hung in 10 Downing Street, and later Houghton Hall. One art advisor at the auction said it was ‘the perfect picture’ and added, ‘it shows that even when sentiment is down, if you bring a ten-out-of-ten picture, the market will respond’. But unusually for an Old Master, it had a diamond symbol on its online listing – indicating that the work carried a third-party guarantee.

Sometimes called an irrevocable bid, a guarantee means that someone – either a third-party buyer or the auction house itself – will buy a work for an agreed but secret price if there are no bids or the work doesn’t meet the reserve. It is a very contemporary financial arrangement for a traditional picture.

Guaranteed works are everywhere. Lindsay Dewar, head of analytics at ArtTactic, says that nearly 73 per cent of lots by hammer value were guaranteed at Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips’s post-war and contemporary evening sales in the first six months of the year. This is a record high – up 20 per cent on last year – and represents a $400m outlay. Guarantees appear in other categories too: 72 per cent of works by hammer value were guaranteed in the Impressionist and modern sales, 11.5 per cent more than last year. Eight other works were also guaranteed in the Christie’s London Old Master evening sale.

Phillips, meanwhile, is trying out a variation on the theme. It has announced that it will reduce its buyer’s premium – the fee buyers pay on top of the hammer price – if the winner has placed a bid on or above the low estimate at least 48 hours before the sale. Martin Wilson, Phillips’s chief executive, says this will provide ‘greater certainty for sellers’ and ‘reward buyers who commit early’, much like guarantees.

A guarantee is a bespoke deal between a seller and an auction house, which often then offloads the risk of having to buy a work to someone else. The guarantee can be set anywhere but is usually at the low estimate or a bit below. In exchange for this security, sellers make concessions. If bidding goes above the guaranteed price, they may have to give away some of this ‘upside’ to the guarantor, typically 15 to 20 per cent, according to insiders. The auction house also does deals on its sellers’ and buyers’ premiums, to come up with a package that the seller, the third party guarantor and the auction house can accept.

The reason auction houses go to all this trouble is because the competition to secure top works of art to sell is fierce. A guarantee is one way to attract a big consignment. But auction houses promise other things too. ‘The consignor, and increasingly third-party guarantors, look to squeeze every last bit of marketing from the auction house,’ a former Sotheby’s marketer says. ‘In the old days it was just the cover on the catalogue. Now it’s videos, digital, marketing and exhibition tours.’

How long guarantees have existed is a matter of debate. Philip Hook, former director of Impressionist and modern art at Sotheby’s, says it offered an in-house guarantee of £35,000 to secure the sale of Nicolas Poussin’s The Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1633–34) – in the face of stiff competition from London’s Old Master dealers – in 1956. But guarantees remained rare until the art market boom of the early 2000s.

The strategy has always been risky. Hook says that Sotheby’s lost £6,000 on the Poussin. Others have fared far worse. In 1999 the French billionaire Bernard Arnault bought Phillips and, according to art market expert Georgina Adam, offered millions in guarantees to secure consignments to compete with its larger rivals. The move backfired. One auction alone – the 2001 sale of the collection of Nathan and Marion Smooke – earned only $85m against a rumoured $170m house guarantee. By 2002 Arnault had sold a majority stake in the firm to the art dealer Simon de Pury, after amassing losses of $400m.

The financial crisis of 2008 was another low. Christie’s and Sotheby’s had gambled millions of dollars to secure consignments. In his book Art of the Deal, Noah Horowitz that says Sotheby’s laid out $902m in 2007 alone. Opinions vary on how much the two houses lost once the market crashed, but the Wall Street Journal reported that by the end of 2008 the two houses were holding an estimated $63m in art they had been obliged to buy.

After this sobering experience guarantees largely disappeared. When they returned, the houses did everything they could to lay off the risk – to financiers and speculators who didn’t have anything to do with art collecting but mostly to collectors, art dealers and other insiders. These have included Peter Brant, Pierre Chen, David Geffen and dealer/collector families such as the Nahmads and the Mugrabis.

Despite their prevalence, guarantees are not liked by everyone. Harry Smith, managing director of art advisory firm Gurr Johns, told the Art Newspaper in 2018 that ‘guarantees have the potential to be the next big art market scandal’ – and there are periodic grumblings about a lack of transparency and boring sales.

The problem, some say, is that guarantees make the apparently transparent auction process opaque, including the real price paid. Felix Salmon, chief financial correspondent at Axios, has described heavily guaranteed auctions as ‘less like anonymised price-discovery mechanisms and more like gussied-up private sales’.

Whether this is true, they are certainly complicated. Auction house staff have to calculate likely results for each of the lots, the level of guarantee the client will accept to clinch the consignment, the likelihood of laying that off to the relatively small pool of guarantors and then work out the degree of risk the house is left with. If this sounds like financial macramé, that’s because it is.

‘Guarantees have certainly increased in “mindshare” over the past five years,’ says Ben Gore, chief operating officer at Christie’s and a former investment banker. ‘Ultimately the choice to take a guarantee is the consignor’s. But then we have to decide if we want to keep the guarantee in-house or reinsure it with a third party, which is part of a risk-management, portfolio approach. But we also reflect on what having a third-party guarantee signifies in the market.’

ArtTactic argues that guarantees can act as a barometer for the market – if you know how to read them. In 2022, when sales bounced back after the pandemic, $1.46bn of post-war and contemporary art carried guarantees. This fell to $858m last year. The $392m guaranteed in the first half of this year compares with £539m in the same period in 2024, ‘underscoring the overall softness in the current market’, as Dewar puts it.

The percentage guaranteed by value is another indicator: the higher the number, the less confident sellers are to put works into auction ‘naked’. By taking a guarantee, they are certain the work will sell – but they could give away a lot of money if it flies past its estimate. The fact that the proportion of guaranteed post-war and contemporary works reached a record 72 per cent suggests that most sellers want a safe bet.

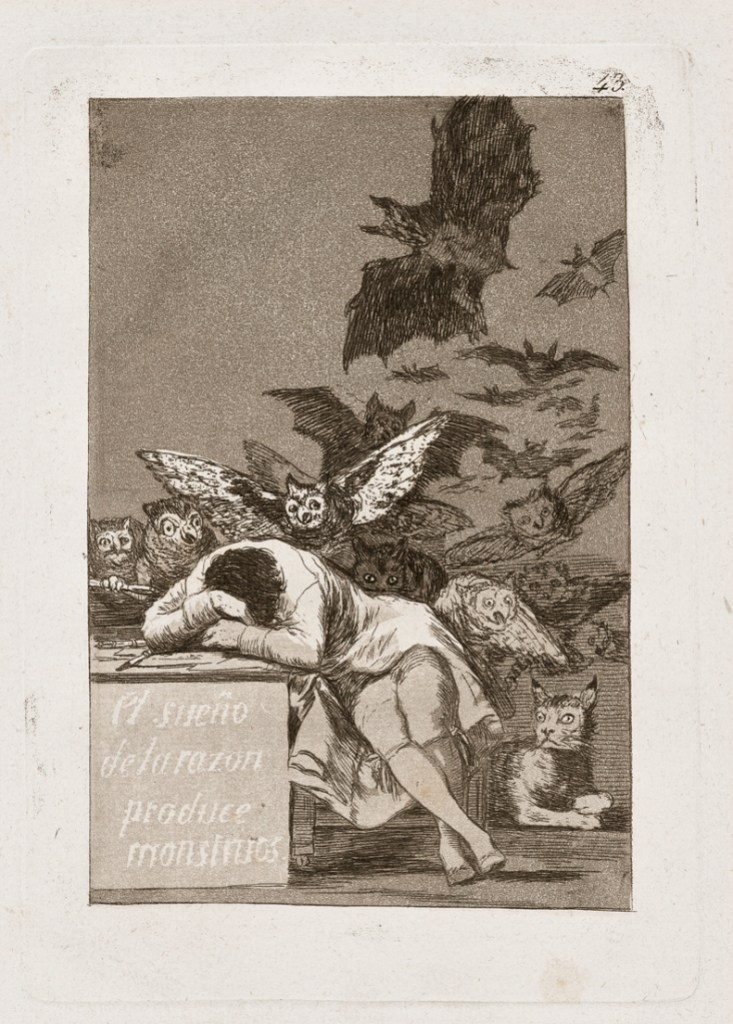

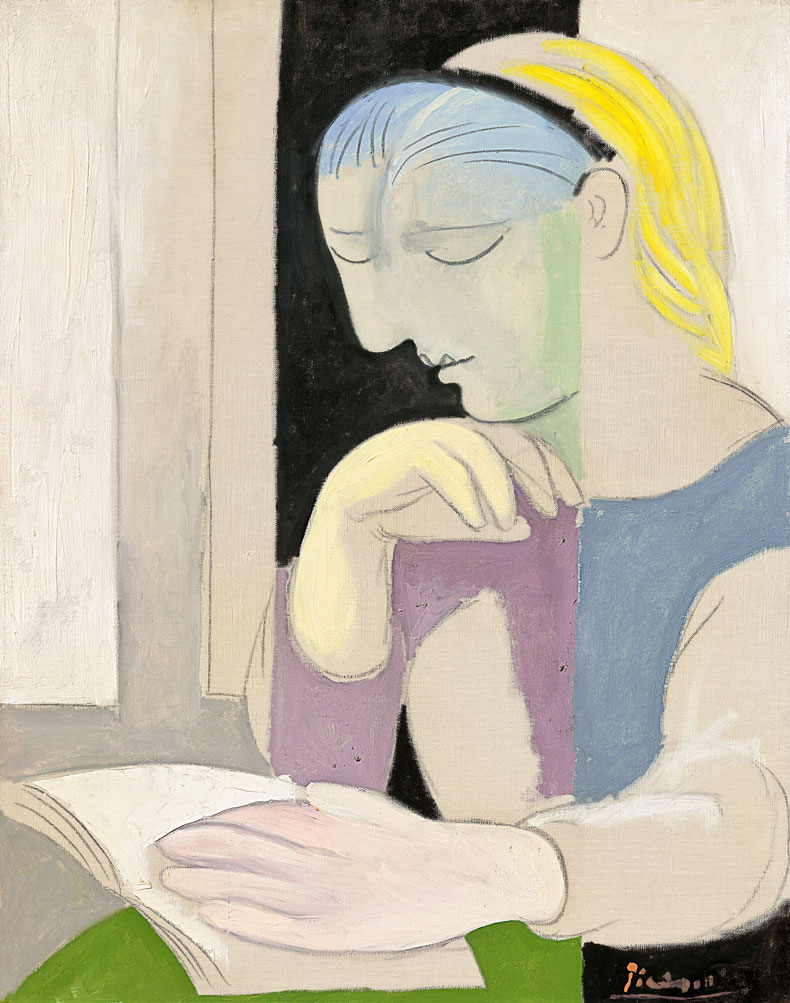

Safety, of course, tends to reduce the excitement around a sale. In November 2023 Sotheby’s sold the collection of Emily Fisher Landau, a patron who had a private museum in Long Island City, New York. The stakes were high: the sale had an estimate of between $344.5m and $430.1m. All 31 lots in its evening sale were guaranteed, including the star lot, a portrait of Picasso’s muse Marie-Thérèse Walter from 1932. While it attracted competitive bidding, many other lots did not, and 13 sold below or at the low estimate, very likely to the guarantors.

‘Basically, there was so much at risk that they left no risk,’ New York-based adviser Wendy Cromwell commented at the time. But the theatre of major sales was already diminishing. High-quality live streams and publicity-shy collectors mean that many more people now log in to watch and bid from home.

Then there is the objection that guarantors have an unfair advantage. They know the reserve: the lowest price a seller will accept. They probably know the auction staff as well because most are also clients. And thanks to the deals on the upside and fees, if there is competition and they win, they have effectively secured the work at a discount.

‘Christie’s pioneered the idea that if you were the guarantor you would always get a discount, whether you had taken a flat-fee deal or a share of the upside. If you continued bidding, you would still get your percentage,’ says Mari-Claudia Jiménez, co-head of art law practice at Withers and former Sotheby’s chair. ‘For some time at Sotheby’s that wasn’t the case. That changed eventually of course, because we were having a hard time attracting guarantors, as they weren’t incentivised to buy a work they guaranteed.’

On the flip side, the presence of guarantors gives other bidders confidence – especially in uncertain times. ‘A guarantee says, “this is a good piece, the estimate is OK and someone else is interested enough to buy it”,’ one art advisor told me. Perhaps more serious is the risk of what could happen if a big, ‘global’ guarantee deal on a major collection goes badly wrong. Margins at the top end of the market are already thin – as low as two per cent, say insiders.

On a $100m collection, an auction house will have waived its seller’s fees and given the seller three quarters of its 20-per-cent buyer’s fees – which leaves little behind for marketing expenses such as international exhibitions, let alone a run of unsold works. ‘When you factor all that in, it is not hard to see how guarantees often end up in the red,’ Jiménez says.

Guarantees are here to stay as long as consignors fear failure at a public auction. In May, Sotheby’s offered a bronze bust, Grande tête mince (Grande tête de Diego) (1955) by Giacometti, with an estimate of $70m but no guarantee. Bidding reached $64m, then stalled. In his recent takedown of Sotheby’s owner Patrick Drahi in the New Yorker, journalist Sam Knight describes the agony of auctioneer Oliver Barker offering the work at $64m 28 times to no avail.

‘At the top end, the number of bidders can be limited and so the risk of failure can be higher than many perceive. You can’t just put a [failed work] back into an auction in six months’ time,’ says Willem-Joost de Gier, co-founding director of art advisory Cadell. And there is a big financial impact. ‘Works that pass at auction lose 32 per cent of their value on average when they finally resell,’ he adds. Meanwhile, most risk ‘giving away’ far less than this as part of the guaranteeing process. As a result, expect all this autumn’s big sales in London and New York – so far the collections of Ole Faarup, Leonard Lauder, Elaine Wynn, and Robert and Patricia Weis have been announced – to be guaranteed.

In a possibly surprising turn, Marc Spiegler, former director of Art Basel, the world’s most important art fair, took aim at guarantees as part of a wider criticism of the ‘financialisation of the art market’ in his column for theBusiness of Fashion website. Partly this is because they have attracted a new class of investors – Wall Street bankers, tech entrepreneurs – who see them as a novel way to make a profit. Their ranks have, unfortunately for the image of the art market, included the likes of fraudster Inigo Philbrick, the subject of a recent BBC documentary.

‘In the past quarter century we have seen various attempts, from investment funds and fractional ownership to NFTs, to treat art as an asset class similar to stocks and real estate,’ Spiegler says. ‘During that period, the art market has actually shrunk.’ He believes that all the talk of financial returns puts off the collectors of the future. ‘There is an argument that speculation has turned off people who might have been great patrons, because they thought it was all about loving art and artists,’ he says. The irony is that guarantees only affect the very top of the market. According to Gore, only 1.5 per cent of lots at Christie’s carry guarantees – although because of the high price of each work, that represents much more by value.

Maybe the tension arises because of the image auction houses have cultivated, more Joseph Duveen than Del Boy. They trade on their own antiquity, their aristocratic connections and their expertise in all kinds of art. Guarantees come from a world of quasi-financial institutions. Look too closely and they remind us that our major auction houses are not so much temples to art but to Mammon.

From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.