The Fontaine Stravinsky (1983) – an assemblage of whirring and spinning contraptions by Jean Tinguely and monumental, brashly colourful creatures by his then-wife, Niki de Saint Phalle – is, today, a beloved Parisian landmark. Yet few of the millions of tourists who pass through the Place Stravinsky en route to the Pompidou will be aware that the sculpture is connected with the experimental Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music (IRCAM), whose offices extend out beneath the basin of the fountain. Fewer still will know that this whimsical, carnivalesque group of sculptures were first suggested to the City of Paris by IRCAM’s founding director, the irascible composer and conductor Pierre Boulez.

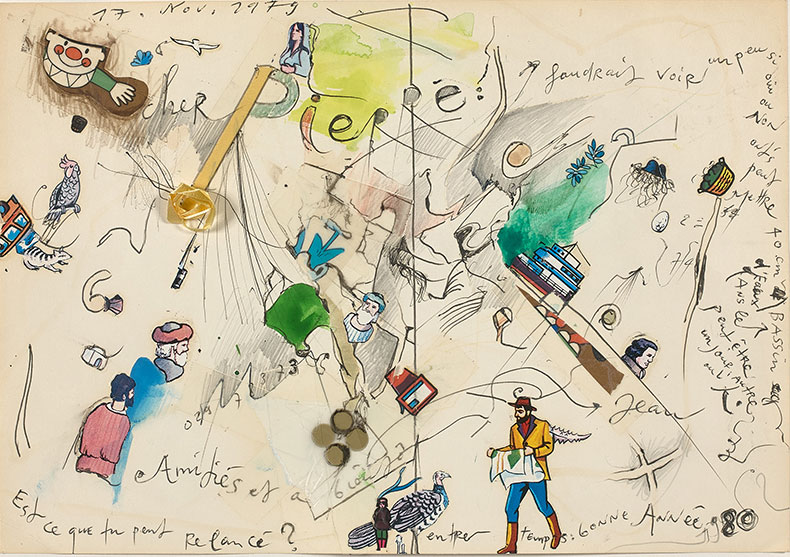

Untitled (c. 1979–83), Jean Tinguely. Set of 12 works on the 1983 Stravinsky Fountain in Paris. Artcurial (estimate €35,000 – 55,000)

At Artcurial in Paris, 12 remarkable sketches setting out Tinguely’s plans for the Fontaine Stravinsky – each addressed ‘cher Pierre’, with little suggestions and explanations in the sculptor’s spidery hand creeping round the margins – go on sale on 7 June. They’re part of a sale dedicated to the collection of Boulez – a fascinating window on the mind of a musician who has become, in the public imagination, an iconoclast par excellence. In the words of his early teacher at the Conservatoire de Paris, Olivier Messiaen, Boulez was ‘in revolt against everything’. He was militant against any music that smacked of reliance on the traditions of previous eras: ‘Do, act, and above all, don’t reproduce,’ he said. With masterpieces like Le Marteau sans maître (1955) or Pli selon pli (1960), Boulez sought to abjure tonal or rhythmic laws – or perhaps more specifically, invent his own in order then to break them.

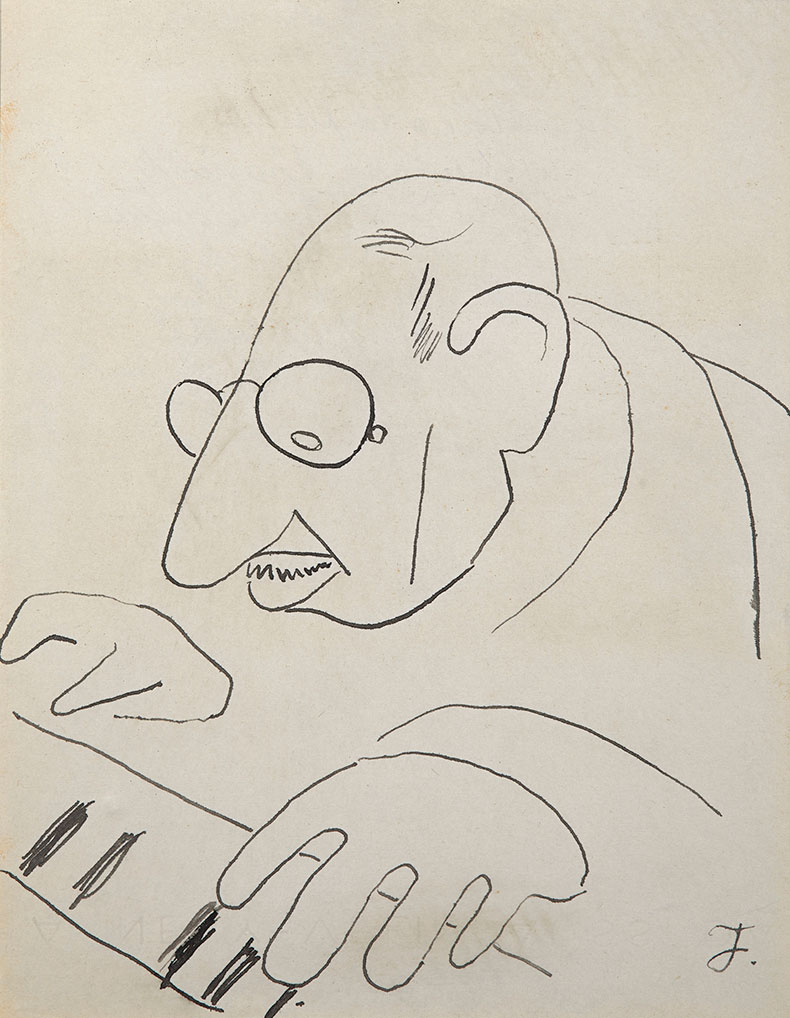

All of this has led some to think of Boulez as a dogmatist. And yet, the works of art he hung on his walls reveal, instead, the composer’s fanciful, searching side. This is encapsulated by a David Hockney postcard depicting Richard Wagner, his face refracted through a glass of water set on top of his visage in an MC Escher-like piece of trompe l’oeil – the po-faced composer, disarmed by a bit of levity and silliness. Not dissimilar is Jean Cocteau’s little ink on paper sketch of Stravinsky playing The Rite of Spring – more quietly amused tinkerer than composer inflamed with the passion of creation. It’s up for €4,000–€5,000; a more sombre pencil on paper portrait of Stravinsky, by Alberto Giacometti, is estimated at €30,000–€40,000, but you can’t help feeling that, perhaps unsurprisingly, there’s a lot more here of Giacometti than there is of Stravinsky.

Igor Stravinsky au piano, Jean Cocteau. Artcurial (estimate €4,000–5,000)

Boulez owned a charming watercolour, Tête créatrice (1917) by Paul Klee, whose paintings Boulez described as a ‘lesson in composition’, and prints by Klee, Kandinsky and Miró – painters whom he credited, alongside Schoenberg or Debussy, as being ‘at the root of all modernity’. But he also took an interest in the visual artists of his own era – many of whom also understood themselves as living in the shadow of the Second World War, and under the spell of existentialist philosophy. (‘History is what one makes it,’ Boulez once said, in words which could just as easily have been Jean-Paul Sartre’s.) Francis Bacon became an important touchstone – he met the artist in London in the 1970s, and acquired signed and dated lithographs of his famous Second Version of Triptych (1944), and of one of his studies of Pope Innocent X, after Velázquez. Boulez owned two early drawings by Philip Guston, and a wide range of works by Nouvelle École de Paris artists – including the original ink-and-watercolour (1958) produced by Zao Wou-Ki for the cover of Les Concerts du Domaine Musical, an album of works performed by one of the many societies Boulez founded (€20,000–€30,000).

Hiver (1983), Maria Héléna Vieira da Silva. Artcurial (estimate €80,000–120,000)

This sale is a world away from the offerings in New York earlier this month. There, the collection of Boston real-estate developer Gerald Fineberg could take in $124.7m at Christie’s and be described by one critic as ‘a shockingly low result’ – part of a broader story of lacklustre sales that have led to suggestions that the market in New York might be cooling at last. Here, the top lot is Vieira da Silva’s oil-on-canvas Hiver (1983), a beautiful rendition of trees shivering in the frosty air, bearing an estimate of €80 000–€120,000; there are works on sale for as little as €100. But as an insight into the way that the composer thought, it’s akin to the experience described by soprano Barbara Hannigan of working with Boulez on Pli selon Pli – ‘every performance was the uncovering of a jewel.’

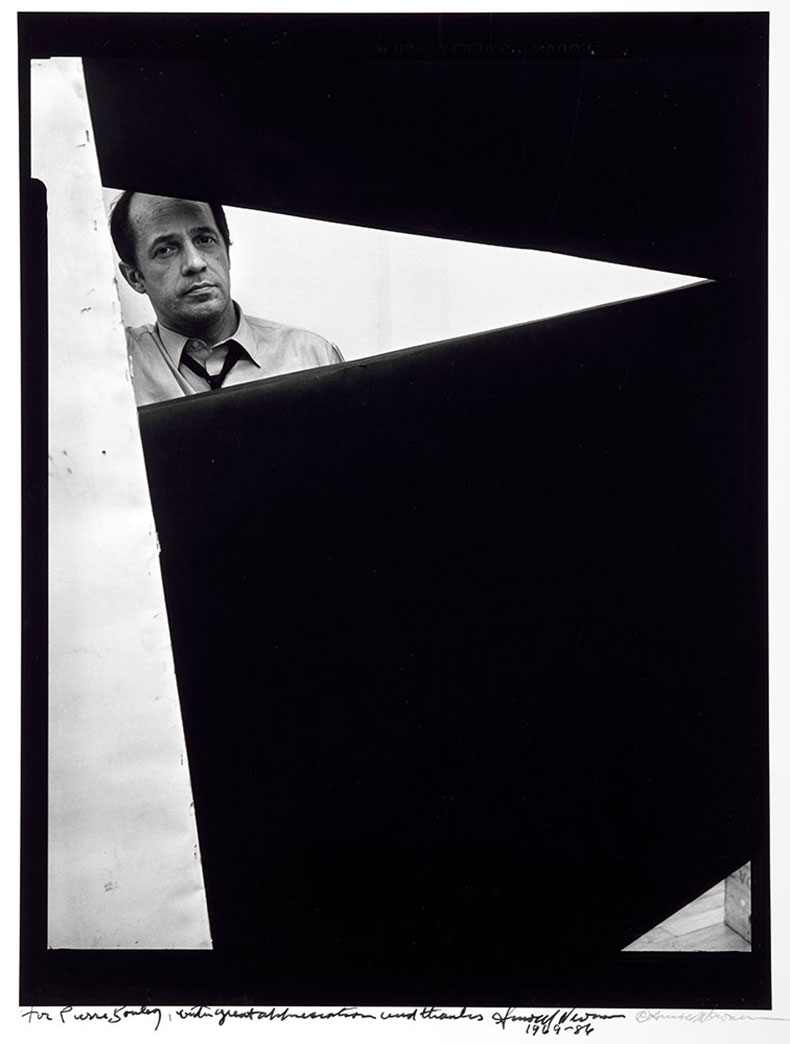

Pierre Boulez (c. 1967), Arnold Newman. Set of 2 silver prints. Artcurial (estimate €20,000–30,000)