In the office of Sabine Haag, director-general of the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna, there is a blown-up photograph that shows her manoeuvring Benvenuto Cellini’s Saliera (1540–43) into its display case in the museum’s Kunstkammer. It’s an eloquent image that – white gloves and all – tells of a museum director whose primary concern was for many years, as a leading art historian, with the research and care of historical objects. The Saliera is far more than an object, of course: it has become an emblem of this museum, perhaps the most flamboyant yet intimate manifestation of the princely culture that shaped its collections. Stolen in 2003 and recovered in a forest in Lower Austria three years later, it is now one of the highlights of the triumphantly restored Kunstkammer galleries, with their unparalleled cache of manmade and natural wonders. Haag, who took up the directorship in 2009, oversaw the reopening of those spaces in 2013 after more than a decade’s closure that had initially been provoked by conservation problems. In a sense, this is a photograph that shows the museum itself being set straight.

This year, the Kunsthistorisches Museum has been celebrating the 125th anniversary of its opening in 1891 – not as consequential a birthday, perhaps, as a centenary or bicentenary but, explains Haag, a good opportunity to take stock of how the museum has developed since it was founded and what it might need to keep pace with the expectations of its visitors and other stakeholders in the decades to come. The late 19th-century vision for the museum, driven by the Emperor Franz Joseph (1830–1916) as part of his broader ‘regulation and beautification of my residence and imperial capital’, had been to bring together the vast and geographically dispersed Habsburg collections and make them publically accessible. ‘The museum still contains the Habsburg collections presented in the best way,’ says Haag. ‘I would think in a better way than 125 years ago, because then the museum was packed with art, and now we’ve cleared it a little bit, and made it more public-friendly over the decades.’

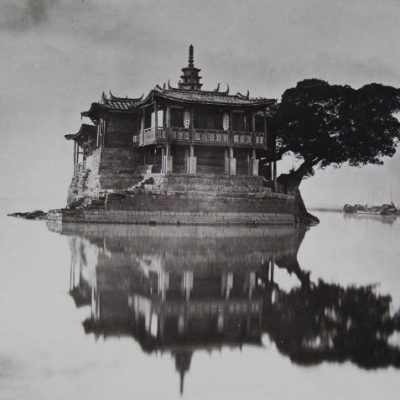

View of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, looking across Maria-Theresien-Platz to the main entrance

That founding mission, and its imperial flavour, are hard to mistake at the museum today. The historicist temperament of the building designed by Carl von Hasenauer and Gottfried Semper – with its four façades that corral statuary representative of different art-historical periods into a grand neoclassical framework, and a decorative programme that relates each suite of galleries to the specific collections housed in them – means that the visitor must engage as much with the moment of the museum’s making as with its array of paintings, antiquities, and Kunstkammer objects. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the architectural trajectory from the entrance on Maria-Theresien-Platz through a series of grand spaces that allude to empires of the past: through the cavernous vestibule (with its oculus recalling the Pantheon in Rome), up the broad staircase (based on the example of the Bourbon palace at Caserta) and into the monumental cupola hall, with its octagonal form that remembers the Carolingian octagon in Aachen Cathedral.

Had Semper’s vision been fully realised, the Kunsthistorisches Museum would have been but one architectural element in a vast ‘Kaiserforum’, incorporating this museum’s twin, the Naturhistorisches Museum, and stretching across the Ringstrasse to connect with a hugely expanded imperial palace. But even though that scheme was later abandoned as war broke out and the Habsburg dynasty folded, the museum itself makes for an extraordinary expression of imperial confidence just decades before the old order ended. ‘When you follow up the flight of stairs, it becomes obvious that it’s the pantheon of the Habsburg collection,’ says Haag. ‘It was Semper’s idea to bring this out in such a clear and monumental way.’

We live in a time that is, at best, deeply sceptical of empires. In The Great Museum (2014), Johannes Holzhausen’s engrossing behind-the-scenes film of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, museum staff discuss whether the institution today should celebrate the Habsburg rulers that shaped its collections, or approach them more objectively; and at one point, an employee expresses surprise that the Treasury (Schatzkammer) – housed in the Hofburg Palace but under the aegis of the Kunsthistorisches Museum – has been renamed the Imperial Treasury (Kaiserliche Schatzkammer) as part of a rebranding exercise to entice tourists. The relationship between the Kunsthistorisches Museum and the state, and the history of that state, is clearly a point of discussion at the museum.

But it would be churlish to dismiss those Habsburg collectors whose tastes and obsessions suffuse the holdings of the Kunsthistorisches Museum with their distinctive strengths and qualities. As Haag says, ‘Franz Joseph was definitely aware that, everywhere in Europe, museums were on the rise, and he sensed that the imperial collections were the greatest collections that were possible at the time, and that they had to be shared with the public.’ Not only do these artworks and artefacts reflect what would have awed the public in the late 19th century, but also what had been most highly esteemed at different junctures in the preceding centuries, not least by the succession of princely collectors who acquired or commissioned them. There is, for instance, that exceptional collection of lapidary work in the Kunstkammer holdings, including the Gasparo Miseroni pieces once owned by Rudolph II (1552–1612) and the works produced by Ottavio Miseroni, many with mounts by Jan Vermeyen, after the establishment of a dedicated workshop at Rudolph’s court in Prague in 1588. So too does the picture collection – with its great strengths in portraiture, in the Venetian Renaissance, early German painting, and the Flemish high baroque – tell of phases of princely taste, and indeed of the new hierarchy between the arts that saw painting become so dominant at European courts during the 17th century. Archduke Leopold Wilhelm (1614–62), regent of the Netherlands in the mid 17th century, brought together some 1,400 paintings; almost all of the 51 works that were pictured by David Teniers the Younger in c. 1651 in the archduke’s gallery in Brussels are in the Kunsthistorisches Museum collection today.

Lapis Lazuli Dragon Cup (c. 1565/70), Gasparo Miseroni. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

But as much as the Habsburg legacy bears evaluation in an anniversary year, at least as pressing is the question of the museum’s relationship to the state today – and not least because, this year, Austria has been forced to confront its national and cultural identity during a presidential election saga that remains unresolved and that may yet see the country become the first EU state to elect a far-right head of state. That this summer’s anniversary exhibition took the theme of ‘Celebration!’, examining the form and function of festivities through history, has perhaps been a welcome diversion; as Haag writes in the catalogue preface, the subject should ‘inspire us to think about the art of celebration in a time decidedly short on lightness and levity’.

The Kunsthistorisches Museum is a national museum, which used to be fully managed by the state but which, since 1999, has been granted Vollrechtsfähigkeit (‘full legal capacity’), allowing it to operate at arm’s length from government and have independence over its direction and programming. It currently receives about 60 per cent of its revenue from the federal government, which is significantly less than it used to, but still far more than comparable institutions in the UK (the British Museum received around 37 per cent in 2014–15 as grant-in-aid). Haag is open about how current political attitudes to culture – and the fact that culture budgets look increasingly dispensable to many European politicians – heighten the need to justify public funding and shift the balance of income in favour of self-generated revenue and fundraising. Of the museum’s temporary exhibition programme, she says that: ‘You really have to find the balance between a blockbuster name and integrating the scholarly component. […] I wish we could afford to integrate the scholarly component much more, but of course the state is withdrawing funding more and more, so we have to look for revenue which comes from large visitor numbers. I think this is a fundamental change that museums are undergoing.’

‘The museum used to be for a very limited range of people, and the display was for connoisseurs, which created a very specialised, very intellectual dialogue between the artworks and the visitor,’ Haag continues. ‘Today, the majority of visitors don’t bring specialist knowledge with them. They need some kind of red thread to lead them through the museum to find out why this or that object is so important. It’s now part of our mission – our responsibility – to get people connected with the arts.’ Still, the evidence of the new Kunstkammer galleries is that this museum is successfully striking a balance between catering to the demands of an increasingly broad audience and meeting the expectations of more seasoned visitors. The explanatory texts and touchscreens in these rooms are accessible yet unobtrusive, meaning that the objects, many of which are displayed in discrete vitrines, are given leave to command the visitor’s attention. ‘We really wanted the art to be in the foreground, very solitary,’ says Haag, ‘so that the visitor wouldn’t be overwhelmed by so much information that they would get tired looking at the art. […] These are such unusual and uncommon objects, in forms and materials that most people are unfamiliar with.’ There is a clear and convincing personal investment here, given Haag’s prior expertise in sculpture and the decorative arts, with a particular focus on the Habsburg ivories: ‘I still look at the ivories as my children, but I’ve handed them over to my colleagues in the Kunstkammer.’

Installation view of Fury (1610/20), by the Master of the Furies (Salzburg?). Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

That displays can be taken seriously while proving popular is a principle that articulates much of the museum’s programme. One good example is ‘Pieter Bruegel the Elder: The Master’s Hand’, an exhibition scheduled to open in October 2018 on the eve of the 450th anniversary of the artist’s death in 2019. The Kunsthistorisches Museum collection contains 12 of around 40 panels attributed to Bruegel, including The Tower of Babel and three of five of the surviving ‘Seasons’ paintings (among them The Hunters in the Snow): it is the largest and most important grouping of his work in the world (the exhibition ‘couldn’t happen elsewhere’, says Haag). From 2012–14, the panels were subject to comprehensive technical analysis as part of the Getty Panel Paintings Initiative, the results of which will feed into the exhibition and its focus on Bruegel’s artistic process and technique. ‘We really will show the process of creative work,’ says Haag. ‘It gives so much more to the public and then they understand why we need the experts, and why they need so much time.’

Hunters in the Snow (1656), Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The ambition of creating a programme that is unique to the Kunsthistorisches Museum and its collections, and that steers clear from the homogenous exhibition-making so prominent elsewhere, is essential to how Haag envisages the growth of the museum’s visitor numbers and the continuing loyalty of its current audience. (Elsewhere in Vienna, the Albertina now resembles something more akin to an international Kunsthalle than the guardian of one of the world’s most important collections of drawings and works on paper.) This imperative has informed the shrewd programme of modern and contemporary exhibitions and events that, under the guidance of adjunct curator Jasper Sharp since 2012, have brought recent work into the ambit of the pre-modern or antique in ways that have been consistently instructive (or as Haag has it, the programme has upheld ‘the vision that this would help us understand the Old Masters in a better way, and what their function is for modern and contemporary art production’). This has involved three approaches to incorporating post-war art in the museum: working with artist-curators (formerly Ed Ruscha, and this autumn, Edmund de Waal), biennial monographic exhibitions of so-called ‘modern masters’ (including, in 2013–14, the first exhibition of Lucian Freud’s paintings in Vienna, the city his grandfather Sigmund fled in 1938), and the annual installation of a single work in the Theseus Temple in the Volksgarten, a structure built in 1819–23 to house Antonio Canova’s Theseus Slaying the Centaur. This summer, the installation was Ron Mueck’s Man in a Boat, created during the artist’s residency at the National Gallery in 2000–02, but here the figure seeming all the more vulnerable, in its nude, shrunken state, for its investiture in a neoclassical temple built for the worship of art.

Installation view of Ron Mueck’s Man in a Boat (2002) in the Temple of Theseus, Volksgarten, Vienna

Another aspect of the 125th anniversary celebrations has been a series of lectures throughout the year by the directors of some of the world’s leading museums. Wim Pijbes, Max Hollein, and Thomas Campbell have all spoken, and Eike Schmidt and Gabriele Finaldi, the new incumbents at the Galleria degli Uffizi and the National Gallery, will speak on 7 November and 12 December respectively. For Haag, it has clearly been a year for reflecting on leadership, and what the museum will need in that regard for the projects ahead. Her second five-year term as director-general draws to a close at the end of 2018, with the possibility that she will be invited to serve a third term by the culture minister. But before that, next autumn, a major project to restore the Weltmuseum, the ethnographic collections that also fall within the director-general’s remit, will be completed; and a feasibility study is underway to explore how the different collections, spread across various buildings with variable facilities, might be rationalised and better connected from the perspective of the visitor by the time the 150th anniversary of the museum rolls around in 2041.

For all that Haag misses curating, it is audiences – and specifically, knowing that the museum’s collections can always be open to them, and that they rely on expertise to be so – that are her chief concern. ‘I’ve really asked our curators and academic staff to develop a feeling for the importance of everything that relates to our audiences – because if they don’t, we’ll really be heading towards some serious problems. As an academic in the museum, you can still do your research, but you need to remember that you’re talking to people who don’t speak your language.’ Franz Joseph would, I think, have found the Habsburg collections and their public in secure hands.

From the October 2016 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.