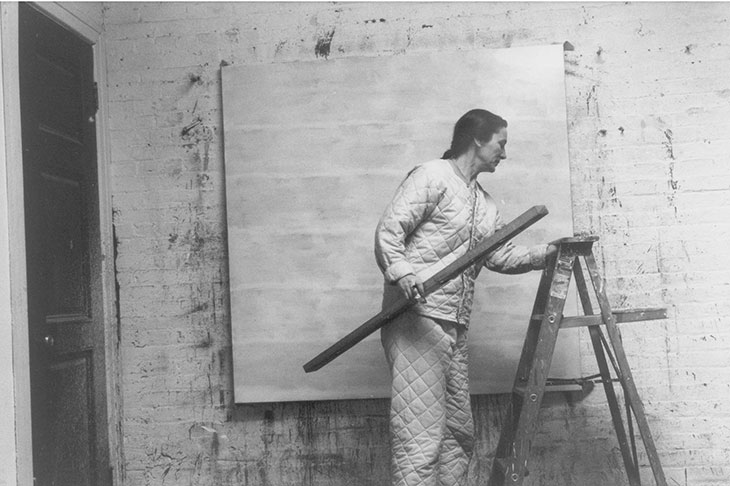

The decision this April by a New York court in favour of the Agnes Martin Catalogue Raisonné LLC (AMCR) in a lawsuit brought by the Mayor Gallery, based in London, is the latest outcome in a series of disputes over the practice of authenticating works of visual art. After an artist’s death, foundations are often created to oversee their work and be the arbiter of what the artist did, and did not, create. Such authentication decisions are often subjective; sometimes works can be proven inauthentic by forensic testing (as was the case in the Knoedler disputes, in which a number of supposedly Abstract Expressionist paintings were shown to be forgeries that used pigments not in existence when the work was alleged to have been created). As often as not, however, it is a question of connoisseurship and scholarship, not science. These decisions by artists’ foundations have, in recent years, become the focus of increasingly high-stakes litigation.

Authentication lawsuits have driven the Andy Warhol Foundation, the Keith Haring Foundation, and the Calder Foundation, for example, to cease rendering opinions about the authenticity of works. These foundations all prevailed in lawsuits, but at great cost – both in terms of legal defence fees, as well as the harder-to-calculate reputational harm from being embroiled in a lawsuit alleging misconduct – that drove them to decide it was not worth the trouble. An authenticator will have a disproportionate amount to lose in a dispute where one side is often expecting a seven-figure upside.

The AMCR began rendering authentication opinions only in 2012. Between 2009 and 2013, the Mayor Gallery sold certain paintings to individual collectors in the belief (and explicitly telling the buyers) that the works were by Agnes Martin. The prices ranged from $2.9 million for Day & Night in 2010, to $240,000 for an untitled work in 2009, to $180,000 for The Invisible in 2012. The gallery also sold 10 works to a single purchaser in 2013 for a total of about $3.6 million. The buyers subsequently submitted the works to the AMCR’s authentication committee after the sales. The dealer had apparently warranted their authenticity to its customers. When the committee declined to authenticate them, Mayor Gallery rescinded some of the sales, refunded the money, and submitted the works again in its own right. The AMCR again declined to authenticate them.

Mayor Gallery filed the lawsuit in 2016 accusing the AMCR of failing to follow its own procedure, and of various other legal theories involving interference and negligence, resulting in a loss to the gallery of more than $7 million. ‘Tortious interference’ is a claim in which a plaintiff argues that the defendant interfered in an existing or potential business relationship, not for legitimate business purposes or competition, but instead to harm the defendant maliciously. Negligence is fundamentally an allegation of carelessness, that the AMCR ignored what Mayor Gallery believed to be important facts.

In response to the lawsuit, the AMCR and its authentication committee made a request for the court to dismiss the case. The presiding judge analysed these various theories in turn, and was dismissive of them all. In particular, the court rejected the interference theories because it concluded there were no allegations that the AMCR had done anything illegitimate or for an improper reason in rendering its opinions. In other words, AMCR did exactly what it said it would do – give an opinion. There is nothing nefarious or purposeful about the effect that that opinion has on the subsequent sale of an artwork. Furthermore, the attempt to find the committee members individually liable fell on deaf ears with the court; there was nothing to suggest they had acted outside the scope of their roles. This dismissal of the individual defendants is one of the most significant aspects of the decision. Far more than on corporations or foundations, the effect that the fear of litigation has on individuals is severe, and the decision underscored clear guidance that where the organisation (the AMCR) is the one performing the service, absent an actual indication of a person’s wrongful conduct (of which there was none), the dispute (if any) lies with the organisation, not the human experts.

The other significant outcome of the case is similarly welcome for authentication committees confronting the possibility of litigation. In American courts, regardless of who prevails, the default rule is that each side pays its own attorneys’ fees. Critical to this case was the ‘examination agreement’ that must be signed to submit a work to the AMCR. That agreement provided for the award of attorneys’ fees if someone who submitted to the AMCR later brought a related lawsuit. Such contract provisions have been common for many years, though they are not universal, and they are enforceable. The court wasted little time in concluding that the AMCR and authentication committee were entitled to their fees in an amount that will be determined later.

Above all, the outcome is a testament to the importance of carefully crafting services agreements ahead of time to protect the ability of an authenticator to render its opinion in good faith. So many authentication disputes have had the collateral effect of putting an authenticator out of business even when it prevails in the lawsuit. While even a successful defendant is unlikely to describe litigation as a pleasant experience, here at least the attorneys’ fees provision will take the financial sting out of it. Likewise, the court was convinced that the AMCR and the authentication committee had done what they had agreed to do in the examination agreement, which clearly outlined the scope of their task. All too often disputes in the art world fester because the parties did not set their expectations clearly ahead of time. While the AMCR clearly did so, it is important to remember that clarifying rights and responsibilities does not require a complicated contract; it can be as simple as a letter agreement.

Such an approach should become standard in the effort to reduce lawsuits that attack professionals giving their opinion. This is further important because of the status of efforts at passing legislation in New York to protect authenticators. A bill proposed a handful of years ago would have required those pleading against authenticators to provide a higher level of detail to prove the plausibility of their claim, as well as a ‘clear and convincing evidence’ burden of proof during the trial, and a one-sided attorneys’ fees provision. That bill was opposed by the Trial Lawyers Association, and was resubmitted more recently in a version that did away with the clear and convincing evidence standard. The future of this new bill, which has passed the New York Senate multiple times, but has not been approved by the State Assembly, is uncertain. Until the law changes, therefore, the question remains what the parties’ expectations were. A little careful thinking ahead of time can really pay off later.

From the June 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.