From the January 2024 of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

This year marks the centenary of Surrealism. In October 1924, first the Belgian poet Yvan Goll and then the French writer André Breton published their respective Surrealist manifestoes. It was Breton’s vision of the movement, with its insistence on the role of dreams and creative strategies that bypassed reason, that eventually won out. But Breton’s version of Surrealism was just one strand among several that spread throughout Europe and beyond in the 1920s.

Belgian Surrealism represented a distinct movement. The Surrealist magazine Correspondance published writing by Paul Nougé, Camille Goemans and Marcel Lecomte that frequently challenged the emphases and pronouncements of French adherents to the movement. Key to Belgian Surrealism was its rejection of automatism, its cerebral nature and its taste for the uncanny. Rather than seeing the potential for subversion in the unconscious, Belgian artists recognised the power of the surreal in everyday objects and situations. The star of the movement was René Magritte (1898–1967), who in 1925 began to make Surrealist works inspired by Max Ernst. He moved to Paris in 1927 but fell out with Breton and went back to Belgium in 1931. After seeing Magritte’s first exhibition after his return, Nougé said: ‘The world has been altered. There are no longer ordinary things.’

Magritte leads the market for Surrealism. In the last 10 years the movement has gained public attention and critical appreciation through significant exhibitions and publications; women Surrealist artists were a key focus of the Venice Biennale in 2022. But, as Thomas Bompard, co-head of modern and contemporary art at Sotheby’s Paris, comments: ‘Magritte’s art can define by itself the aesthetic of Surrealism – the dreams, the illusions, the imagination and the conceptual play.’ While the work of Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, Salvador Dalí and others is ‘very referential, with links to literature, poetry and psychoanalysis, the beauty of Magritte’s images is that they can be recognised instantly, without any background,’ Bompard suggests.

Sotheby’s holds the artist’s auction record for L’Empire des lumières (1961), sold for £59.4m at Sotheby’s London in March 2022, a price chivvied by an in-house guarantee. This painting is one of a series of 17 on the same theme. The earliest version, dated 1949 and once owned by Nelson Rockefeller, achieved a then-record of $20.5m (estimate $14m–$18m) at Christie’s New York in 2017. In November 2023 the same painting sold for $34.9m (estimate $25–$35m) at Christie’s New York. ‘The most recent development is that his most important work can be sold anywhere,’ Bompard says. In October, Sotheby’s Paris sold a fruit painting, La valse hésitation (1955), for €11.1m, again against a guarantee, though another work did not find a buyer. Olivier Camu, deputy chairman of Impressionist and modern art at Christie’s London, has been running the Art of the Surreal sale since 2001. ‘Magritte is the head of them all,’ he says. Camu has seen the market expand from Europe and the United States to encompass East Asia. ‘Japan has always understood Surrealism,’ he adds.

Les Mains (1941), Paul Delvaux. Christie’s New York, $6.6m

Another Belgian artist, long collected in the country of his birth, is Paul Delvaux (1897–1994). Although a wary admirer of Magritte, Delvaux associated with the Belgian Surrealists for only a brief time. He developed a personal iconography of classical architecture, mythological symbolism, trains, skeletons and naked women in dreamlike landscapes, combining a Surrealist flair for anachronistic juxtapositions with an academic style of painting. Though he was prolific for many years, Delvaux is considered to have been at his peak from 1936 to 1941. A then-record £2.9m achieved at Christie’s London (estimate £800,000–£1.2m) in 1998 for the large canvas La ville inquiète (1940–41) set off a period of unrealistic estimates and unsold paintings. Though Delvaux’s works have long been admired, they do not have Magritte’s universal appeal, Camu says. However, Camu is reintroducing them at sales, with good results. In 2011 Les Mains, also from 1941, sold at Christie’s New York for $6.6m (estimate $6m–$9m). In 2017 Le village des sirènes from 1942 sold for £3m at Christie’s London (estimate £1.7m–£2.5m), while in 2022 the characteristic late work, Le soir tombe (1970) fetched £1.9m (estimate £1m–£1.5m) at the same auction house. Beyond these two giants, Camu extends his definition of Belgian Surrealism to include the work of James Ensor, Léon Spilliaert and Gustave van de Woestyne, among others.

Thirty years after his death, Delvaux will be the special guest of honour at BRAFA in Brussels this January. Exhibitors offering works by the painter include the gallerist and BRAFA chairman Harold t’Kint de Roodenbeke, who suggests that Delvaux’s best work comes after the death of his domineering mother in 1933 and before 1960. He will show the watercolour La danse macabre (1934) – ‘one of his first Surrealist works,’ t’Kint de Roodenbeke says. Eduard Eykelberg, of the Antwerp-based gallery Van Herck-Eykelberg, will bring two works on paper: an ink drawing from 1946 titled L’escalier (€22,000) and L’annonciation, a watercolour work from 1952 (estimate €20,000).

There is modest interest in some of the minor figures surrounding Magritte such as Marcel Mariën, says Augustin Nounckele of Monaco-based dealership Galerie Retelet. ‘Ninety per cent of Mariën’s market is in Belgium,’ Nounckele says. ‘Internationally, people do not look at his work because they see nothing from the classic Surrealist period – the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s – but he made his most significant contribution to Surrealism in the 1970s.’ In June 2023 his collage Pompéi, an 79 : grand coït de la dernière nuit (1984) sold at Bonhams Brussels for €19,840 (estimate €2,500–€3,500). Galerie Retelet is mounting a display of Belgian Surrealism for TEFAF Maastricht this year. Besides Magritte, Delvaux and Mariën, it will also show the work of two women: Jane Graverol and Rachel Baes.

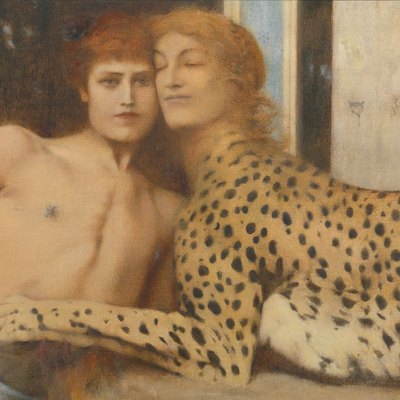

Personnage debout , 1959, Jane Graverol. Bonhams New York, $70,350

The rise in auction results for Graverol in 2023 was remarkable. In March 2022 at Sotheby’s Paris, La déesse raison (1959) leapt from an estimate of €2,600–€3,500 to €47,880. Eight months later, also at Sotheby’s in Paris, Le Chant du Cygne (1958) achieved €88,200. The artist’s most sought-after works are her silhouettes of naked women with landscapes filling Magrittean gaps where their bodies should be. At Sotheby’s London in March, a painting called L’Esprit Saint (1965) achieved £508,000; 19 days later, Le trait de lumière (1959) sold for €579,975 at Bonhams’s inaugural Surrealist sale in Paris. In June, La chute de Babylone (1967) reached €508,400 at Bonhams in Brussels. Sabine Mund, head of the Belgian and modern art department at Bonhams Brussels, says: ‘This market is international. It is not just Belgian collectors: they are from the USA, China, France. The question is, will it last?’ Two works with estimates of €70,000–€100,000 failed to sell at Sotheby’s Paris in October, though a painting with a more modest estimate featuring a man’s silhouette, Personnage debout (1959), sold for $70,350 at Bonhams New York in November. The work of Rachel Baes has yet to reach these heights, but her painting Oedipe et Le Sphinx (n.d.) sold for €16,575 at Bonhams in Paris in March. As new perspectives bring different artists to the fore, the market for Belgian Surrealism will undoubtedly evolve.

From the January 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.