Family histories are rarely straightforward. When it comes to Bernard Leach (1887–1979), often dubbed ‘the father of British studio pottery’, the relationship between the patriarch and his potting progeny is one of devotion and discontent, ruptures and reunions. At the pinnacle of his powers, Leach held more sway over ceramic culture in Britain than anyone else. Yet by the time of his death, some critics held him responsible for stunting the natural growth of a discipline: what once was groundbreaking had become dull and dogmatic.

This year marks a century since the Leach Pottery was founded in St Ives. To celebrate, a host of international exhibitions had been planned: from ‘Started it in England’ at the Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art in Japan to ‘Kai Althoff: with Bernard Leach’ at the Whitechapel Gallery in London (both were scheduled to open this month). But, with the Covid-19 pandemic leaving so many events in limbo, one of the few certainties left in the calendar is the anniversary itself. The opportunity to reflect on a figure whose reputation has evolved as Leach’s has done is an interesting one.

Ceramics aficionado or not, anyone who has held a chunky, earth-toned piece of tableware has witnessed the Leach legacy at work. The phrase ‘brown pots’ – uttered either fondly or with a roll of the eyes – is shorthand for the aesthetic tradition Leach established during the first half of the 20th century. Characterised by wheel-thrown pots, decorated with oriental-inspired glazes then fired in a reduction kiln, ‘Leachian’ has often been used to convey an absence of aesthetic ambition. Yet this says more about the failures of Leach’s followers – arguably as a result of his dogmatism – than it does about the pioneering potter himself.

The son of a high court justice, Leach was born in colonial Hong Kong and spent his early years in Japan. Aged ten he was sent to England, where an unhappy schooling was followed by an equally unhappy stint at a bank. Studying art offered a way towards a more exciting life – first at the Slade School of Art, then the London School of Art, where he learned etching under Frank Brangwyn. Enchanted by the popular author Lafcadio Hearn’s romantic tales of Japan and stirred by memories of his own early life, Leach returned to Japan in 1909. His self-confident intention was to introduce the Western art of etching to the East. Instead, he became bewitched by the country’s native culture: a romance that would last the rest of his life.

In 1911, at a party in Tokyo with members of the Shirakaba-ha (‘White Birch Society’), a group of young, Westernised intellectuals, Leach experienced pottery-making for the first time. Invited to decorate a piece that was fired before his eyes in a portable raku kiln, Leach was enthralled. He found himself a teacher who belonged to a once-illustrious dynasty: Kenzan VI, descendant of the renowned 17th-century potter Ogata Kenzan. Leach learnt the rudiments of how to throw on the wheel and decorate.

During this formative period he became close to the philosopher and art critic Soetsu Yanagi, founder of the Mingei (‘folk arts’) movement: a friendship that shaped much of his later thinking. It was here that Leach developed the ideas that remained solidly in place for the rest of his career as a potter, writer and advocate for his medium. Yanagi’s Arts & Crafts-inflected ideals were important; John Ruskin and William Morris were clear forebears, with their thinking on the meaning and value of craft in an age of mechanised industry. The notion of ‘truth to materials’ was key. Valorising the humble surface of fired clay was one of Leach’s most important gifts to Western pottery; to that end, he often left the feet of his pots unglazed. ‘The foot is a ringing symbol,’ he wrote, with characteristic poeticism; ‘here do I touch the earth, on this I stand, my Terminus.’

After only a year’s tuition, Kenzan VI gave Leach, together with fellow student Kenkichi Tomimoto, the right to assume the title Kenzan VII. This peculiar decision conferred a gravitas on the young art student – and formed a foundational part of his personal myth, as he went on to present himself as a unique bridge between West and East. Yanagi also promoted the idea that Leach held some quasi-mystical insight into his country, going so far as to write: ‘He probably got nearer to the heart of modern Japan than the ordinary Japanese ever did. It is doubtful whether any other visitor from the West ever shared our spiritual life so completely.’ In around 1916, Yanagi invited Leach to join the bohemian artistic community in Abiko, a village outside Tokyo – an invitation he accepted with alacrity. A small yunomi (cup) made in 1919 is rather sweetly decorated with the kiln and studio he established in this rural idyll. Here Leach’s interests turned increasingly to the folk craft traditions of Korea, China and Japan – and, for the first time, to Britain’s own rich history of pottery.

Yunomi (cup; 1919), Bernard Leach. © Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts

Discovered through illustrated books, slipware by the 17th-century Staffordshire potter Thomas Toft caught Leach’s eye: caramel-coloured earthenware densely decorated with mermaids, maidens and monarchs. The graphic qualities of the pots, enhanced by a sense of connection to a homegrown tradition, inspired the slipware Leach made for the rest of his life. His large plates are adorned with a motley array of motifs: Japanese wellheads and weeping willows sit alongside European heraldic beasts and Toft-like crosshatchings.

Charger (1929), Bernard Leach. Courtesy Maak Contemporary Ceramics; © The Bernard Leach Family. All rights reserved, DACS 2020

The other key influence was the Chinese ceramic tradition of the Song dynasty (960–1279): elegant stoneware in simple forms, with asymmetric, spare decoration. In England, these archaeological finds were rapidly displacing porcelain as the desirable ceramics du jour. Leach would coin the phrase the ‘Sung [Song] standard’: a level of unpretentious, authentic artistry to which he believed all contemporary potters should aspire. To this end he created vases, bowls, lidded caddies and more Song-like stoneware decorated with oriental glazes such as tenmoku, celadon and the soft grey-greens of wood ash glazes. A romanticised East met an equally partial West, creating an eccentric hybrid the ceramics scholar Julian Stair as described as ‘a new modernist phase of orientalism’.

Pilgrim bottle (c. 1960), Bernard Leach. Courtesy Maak Contemporary Ceramics; © The Bernard Leach Family. All rights reserved, DACS 2020

In 1920, confident in his abilities, Leach returned to England to set up a pottery in St Ives. With assistance from his friend Shoji Hamada, who helped fill the many gaps in Leach’s technical knowledge, he constructed a wood-burning climbing kiln – the first noborigama to be built in the West. What followed were a series of practical problems: Cornwall lacked the necessary quantities of wood for firing, while local clay was poor quality. At the time, there were no ceramics how-to books: the British studio potter was necessarily an autodidact. Added to this Leach was not, and did not pretend to be, an excellent thrower, viewing himself rather as the ‘composer-conductor’ of the small orchestra that was his pottery. Alongside an uneven and experimental production of pots, Leach began publicly pushing the positions he would come so forcibly to represent.

‘What have the artist potters been doing all this while?’ he wrote in A Potter’s Outlook (1928). ‘Working by hand to please ourselves as artists first […] we have been supported by collectors, purists, cranks or “arty” people, rather than by the normal man or woman […] Consequently most of our pots have been still-born: they have not had the breath of reality in them: it has been a game.’ As for Morris before him, the economic conundrum of how to hand-make beautiful objects – while not ministering solely to the ‘swinish luxury of the rich’ – was tricky.

Leach’s solution was to split his output in two: time-intensive exhibition pieces on one hand; affordable tableware on the other. However, his lack of commercial nous led towards financial ruin, as did the post-war collapse of the collector’s market. It took his son David learning workshop management in the potteries of Stoke-on-Trent (much to his father’s snobbish disgust) to save the Leach Pottery. This was done in part by establishing a range of ‘standard ware’: solid, rustic-looking tableware combining Westernised forms with stock oriental glazes. These pots could be thrown in their thousands by the artisans Leach relied upon – a mixture of what he called ‘local lads’ whose ‘horse-sense’ was invaluable, alongside middle-class art students in search of a poetic vocation.

Vase with ‘leaping fish’ design (late 1960s), Bernard Leach. Courtesy Sotheby’s; © The Bernard Leach Family. All rights reserved, DACS 2020

One area in which economic expedience and artistry combined happily was in that of two-dimensional decoration. Vases designed with a single view in mind, such as those with his favourite leaping fish or tree of life motifs, are satisfying – but only from the correct angle. Leach’s most successful pieces are tile panels such as Wellhead and Mountains (1926–29), which speak to his finely honed graphic skills. His draughtsmanship brings a human touch to work that might otherwise verge on austere. ‘The pot is the man,’ he was fond of saying; ‘his virtues and his vices are shown therein – no disguise is possible.’ Likewise, he described the vessel in bodily language – lip, neck, shoulder, belly, foot – and in terms of human qualities, with quietness or strength being favoured characteristics. It’s not hard to draw parallels between Leach – a reserved, dignified figure, throwing clay in a spotless white shirt, tie and tweeds – and the solemn propriety of his pots. Michael Cardew, his first apprentice, described Leach as ‘a perfectly preserved Edwardian’. His was a deeply romantic vision, with throwing viewed as a spiritual, cosmic act. Mysticism became increasingly important throughout Leach’s life; in 1940, he adopted the Baha’i faith.

Wellhead and Mountains (1926–29), Bernard Leach

Despite the idiosyncrasy of Leach’s East-meets-West output and ideas, he expressed these so often and with such solemn conviction in numerous books, talks and tours that by the 1950s they had become doctrine. A Potter’s Book (1940) had the greatest impact: even today, its mixture of poetry, philosophy and practical instruction earns it the soubriquet ‘the potter’s bible’. For decades, Leach’s reputation was unparalleled. His accolades ranged from a CBE to the Order of the Sacred Treasure in Japan; in 1987, the Royal Mail even chose a Leach vase to adorn a postage stamp.

Leach’s reputation shifted across the century, however, and for a range of reasons. The charge of hypocrisy – of making collectors’ trophies while preaching about peasant pottery – was an issue of which Leach was well aware, and one he struggled to counter. Another problem was the question of critical mass. Once you have influenced a large school of potters who, to varying degrees, emulate your own work, there inevitably comes saturation and ensuing fatigue. This first emerged in the ’50s, as a handful of potters such as William Newland and Margaret Hine took colourful Mediterranean tin-glazed wares and Picasso’s playful pots as their cue; Leach scornfully dubbed this group ‘the Picassettes’. Work by Lucie Rie and Hans Coper represented another, more sleekly urbane alternative to the rusticism of Leach’s pieces. (Rie was crushed by his judgement of her early work, yet in 2020 those vessels Leach damned too thin-walled and thickly glazed, and devoid of human expression easily outprice his own at auction.) Another stylistic shift occurred in the ’70s as a new generation emerged from the Royal College of Art; ceramic artists such as Carol McNicoll, Alison Britton and Richard Slee sculpted witty postmodern pots that owed nothing to the Anglo-Japanese tradition, which was left looking over-earnest and dowdy.

In 1998, Edmund de Waal’s revisionist monograph Bernard Leach sent shockwaves through the pottery world. It lifted the curtain on the great man’s careful cultivation of his own myth; his limited knowledge of Japan, outside of that shown to him by a rarefied intellectual circle; his inability to read or write the language of the culture he claimed to represent in the West. (Leach did learn to speak Japanese to a conversational standard.) Leach’s unapologetic orientalism is particularly uncomfortable. Written by a man who trained in the Leach tradition before making a radical break, it reads like an Oedipal cri de cœur: the writer Tanya Harrod has described De Waal’s book as ‘patricidal’.

Leach’s approach to national character is apparent in his reassertions of ‘thankfulness that I had been born in an old culture […] The sap still flows from a tap-root deep in the soil of the past, giving the sense of form, pattern and colour below the level of intellectualisation.’ For nations younger than England or Japan, this posed a problem. ‘Americans have the disadvantage of having many roots, but no tap-root, which is almost the equivalent of no root at all.’ This fails, of course, to consider the long traditions of indigenous peoples. The failure to value variety appears repeatedly. Despite his own mish-mash of influences, this lack of cultural flexibility led to Leach’s approach becoming associated with an insular academicism, wrought by both Leach himself and his less inspired followers. As his biographer Emmanuel Cooper lamented: ‘Bernard, what crimes are committed in thy name.’

Decades after Leach’s death, the debates about his achievements are yet to be resolved. But the ideas that coalesce around him – of national identity, of the role of art and craft in everyday life, of the value of satisfying work – are no less pressing today than they were in 1920. In a world where the digital-weary yearn for tactility and ‘authenticity’, and urban potteries and evening classes proliferate, Leach’s vision still has its part to play. His is an ambivalent legacy, one that irritates and inspires in equal measure.

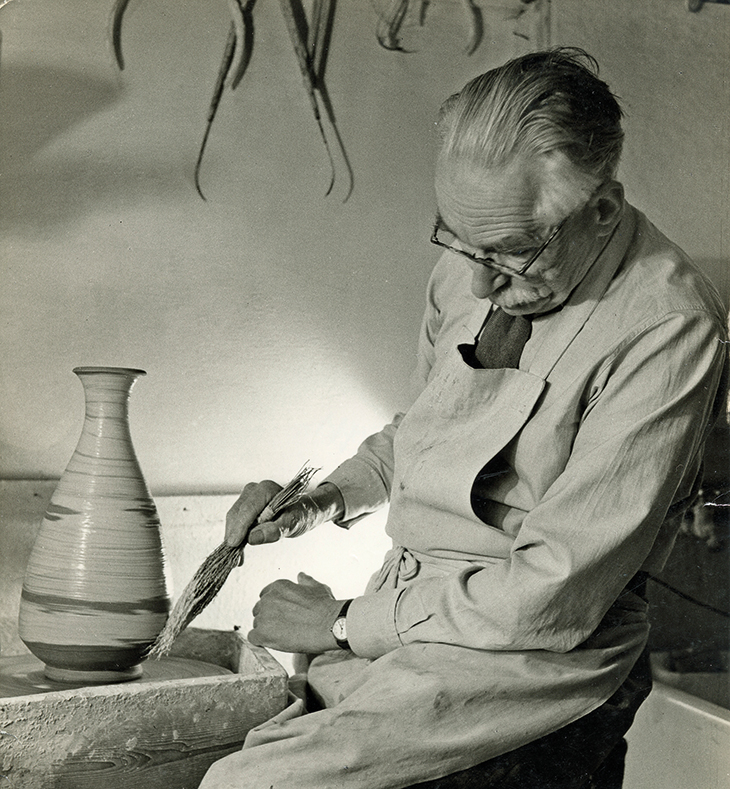

Bernard Leach working at the wheel, applying decoration to a stoneware pot with a hakeme twig brush at the Leach Pottery, St Ives, in 1963. Courtesy the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts; © The Bernard Leach Family. All rights reserved, DACS 2020

From the June 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

This article originally followed Edmund de Waal’s Bernard Leach (1997) in stating that Leach did not speak Japanese. In fact, Leach did learn to speak Japanese and several recordings survive of him doing so, including those held by the Mingei Film Archive and the Crafts Study Centre, Farnham. The article was amended on 5 August to reflect this information.