Early on Easter Sunday, 1897, a group of racing cyclists set out from Porte Maillot on the north-west edge of Paris. Their destination was Roubaix, an industrial town on the Belgian border. The 280km route ran through grim coal-mining country, along tracks of uneven cobbles that rattled the handlebars so badly it gave the riders nosebleeds. The 58 entrants were a mix of hardbitten professionals and spirited amateurs. The latter group included an impoverished, 21-year-old violin teacher who was hoping to eke out his earnings with prize money from racing. But it was not to be that day: he dropped out long before the finish. The victor was Maurice Garin, who would become a national hero when he won the inaugural Tour de France six years later in 1903. Around that same time the young violinist would find himself edging towards celebrity, too. It was neither music nor cycling that would make him famous, however. The aspirant racing cyclist was Maurice de Vlaminck, the self-described ‘tender barbarian’ of French painting, co-founder of Fauvism.

The starting line at Porte Maillot for the Paris-Roubaix race in 1897

To the outside world bicycle racing and art might have seemed polar opposites, but to Vlaminck they were interrelated. Born in urban Paris, he credited the bicycle with giving him his ‘love of the open air, space and liberty’. It was in the saddle, pedalling hard through the countryside of the Île-de-France that he had first become ‘intoxicated with the light’.

Vlaminck was not alone in attributing his discovery of a wider world to his acquisition of a bike. Mobility is an essential condition of freedom, and until the invention of the modern bicycle in 1885 such freedom had been the province of those wealthy enough to buy and stable horses. The mass-produced bike was cheap. As the Victorian novelist Walter Besant wrote: ‘There are none so poor as not to afford a bi-cycle.’

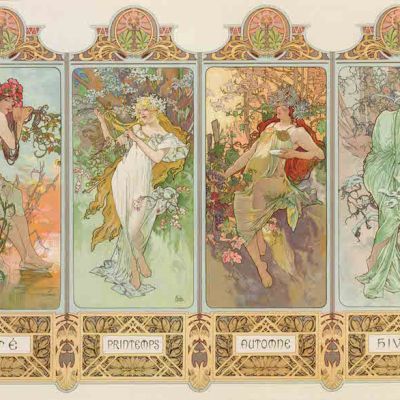

The new machine offered the chance of travel for people to whom the opportunity had previously been denied. This was particularly true for young women. The bicycle heralded a new age of female empowerment. Groups of women rode unchaperoned around the highways and byways of Europe, often meeting up with young men who were doing the same. Moralists spluttered that the bicycle was a dangerous facilitator of clandestine romance. This was, of course, part of its appeal, and bicycle manufacturers did not shy away from capitalising on it. Alphonse Mucha’s art-nouveau poster of 1898 for Cycles Perfecta, in which a bare-shouldered young woman drapes herself across the handlebars and fixes the viewer with a sleepy-eyed gaze, is representative of a style that emphasised the bicycle’s unlikely status as a symbol of sensual delight.

Mucha’s model is hardly dressed for a competitive bike ride (indeed she is barely dressed at all). The same was not true of the young woman who appeared in Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s poster of 1896 for Simpson bicycle chains. The European women’s champion Lisette Marton was one of the first female sports stars. In an era when women were forbidden from running in the Olympics for fear the exertion would kill them (such prejudice, in moderated form, would persist for many years – until 1972 women were not allowed to run any distance greater than 800m at the Games), the exploits of the Breton racer, who often rode against men and beat them, struck a blow for equality.

Toulouse-Lautrec was a great cycling fan. He was introduced to the sport by his friend Tristan Bernard, director of the celebrated Parisian cycle track Vélodrome Buffalo – home to the gruelling Bol d’Or race, which saw riders circling the track for 24 hours, often falling asleep at the handlebars and crashing into one another. In 1895 Toulouse-Lautrec would paint the rotund, bushy-bearded Bernard standing on the velodrome track surveying the empty stands. Paul Signac’s sunnier pointillist Le Vélodrome (1899) is also, in all likelihood, Vélodrome Buffalo, though Paris had many cycle tracks at that time – including the Vélodrome d’Hiver, which had a darker part to play in the later history of France.

Le Vélodrome (1899), Paul Signac. Private collection. Photo: Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo

It was through Bernard that Toulouse-Lautrec secured a contract to design an advertisement for Simpson. He travelled to Catford Velodrome in east London to make the preliminary sketches. The Frenchman produced two posters for Simpson. One, which the company rejected, featured the tiny Welsh world champion Jimmy Michael (possibly the first, though by no means the last, cyclist to be accused of using performance-enhancing drugs). The other focused on French endurance star Constant Huret – a four-time winner of the Bol d’Or – who is seen riding in pursuit of a tandem, the rear rider of which is Marton.

By the start of the 1900s, bike racing was the most popular spectator sport in France, Italy and Belgium. The Bordeaux-Paris race was first run in 1891, Liège-Bastogne-Liège a year later, Paris-Brussels in 1893. The Tour de France came in 1903, and two years later Italy got her first one-day classic with the commencement of the Giro di Lombardia. The Giro d’Italia was first raced four years after that.

Tens of thousands of cheering fans stood by the side of the road for the big races, or flooded into the velodromes for six-day events characterised by heavy betting, wild drinking and the sort of raucous merriment more akin to that at the Moulin Rouge than to the restrained atmosphere of athletics, tennis or golf. Most of the top riders were working-class (Garin had been a chimney sweep, Marton was the daughter of a carpenter). Artists from the Parisian avant-garde were drawn to them and the egalitarian future they epitomised.

The Paris-Roubaix race that Vlaminck had failed to complete quickly became a fixture of the cycling calendar. It was a race so infamously tough it was nicknamed the ‘Hell of the North’. In 1912 the painter Jean Metzinger travelled up to the Roubaix velodrome to make sketches of the finish. Metzinger was a bike-race fan and amateur rider who’d once won a bet by cycling 100km non-stop around the track in Vélodrome d’Hiver (one of the witnesses to this feat was his pal, Vlaminck). In Roubaix Metzinger watched transfixed as a clutch of seven riders – four French, three Belgian – who had broken away from the rest of the field whirled around the concrete track until one of the Frenchmen, Charles ‘The Bull of the North’ Crupelandt, burst to the front and sprinted across the finish line.

Just as travelling on railways had radically altered the approach of painters such as Paul Cézanne, so bicycle racing would help shape Metzinger’s work. Artists had previously looked at objects from a fixed point. In the velodrome this was impossible, the views of the rider constantly shifting as he looped around the track. Metzinger had begun as a Fauvist, but in 1908 began the experimental faceting of forms that would become Cubism. Au Vélodrome (1912), his painting of Crupelandt’s triumph in Roubaix, with its multiple perspectives and chronological shifts, is a timeline of victory compressed into a single vigorous image, one of the first and undoubtedly greatest modernist depictions of a sporting event. Metzinger would become one of the most influential artists of the first part of the 20th century. Crupelandt’s fate was less happy. After winning Paris-Roubaix a second time in 1914 and serving with great gallantry in the First World War, he was briefly jailed for selling car batteries on the black market and emerged from prison to find the French Cycling Federation had revoked his professional licence. Unable to race, the Bull of the North ended his days penniless and destitute, so sick with diabetes that both his legs had to be amputated. Today a cobbled section towards the end of the Paris-Roubaix race is named after him.

The appearance of Metzinger’s painting of Crupelandt’s triumph irked a recently formed group of young artists in northern Italy. For F.T. Marinetti and his fellow Futurists the bicycle, with its speed and turbine-like wheels, the rider hunched over his handlebars, legs pumping like pistons until he seemed to fuse with his machine, was the embodiment of the modern machine age they exalted. Rejecting the decadence of Paris, they determined to claim the bicycle for Italian art and for themselves.

Cycle racing had come to Italy only slightly later than it had to France and if anything had been embraced with even greater fervour by the public. Riders such as Luigi Ganna, Carlo Galetti and Costante Girardengo were among the first national celebrities in a country that was barely four decades old. At first, as in France, Italian artists had emphasised the romance of the bicycle, linking it to ancient mythology. Plinio Codognato’s poster for Atala cycles featured a centaur, while Orlando Orlandi’s for Cellina depicted Vulcan and Venus, the god of fire apparently engaged in forging his faithless lover a new set of wheels – a more original gift than the usual diamonds.

Dynamism of a Cyclist (1913), Umberto Boccioni. Gianni Mattioli Collection

The Futurists had no interest in such backwards-looking flummery. To them, sport and industrial society were inextricably linked. The rider’s interminable pursuit of victory, pedalling fast in order to pedal ever faster, literally and metaphorically carried him away from the antiquated Europe they despised. The Futurist manifesto exalted the bicycle: ‘Everything moves, everything turns quickly, a figure is never stable in front of us, but appears and disappears incessantly.’ In 1915 Marinetti, Mario Sironi and Umberto Boccioni signalled their commitment by joining the Lombard Voluntary Cyclist and Automobile Driver Battalion of the Italian army.

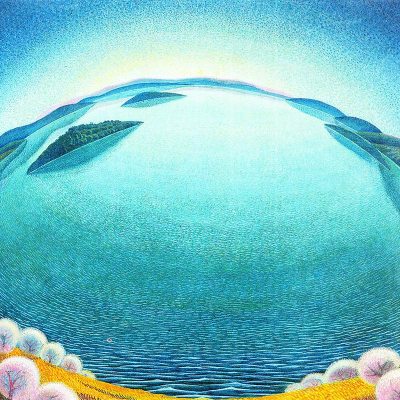

As a young artist Boccioni had produced posters for Frera’s bicicletta a motore, generic art-nouveau-inflected works not unlike, though nowhere near as gorgeously stylish, those of Mucha. Now he threw aside romantic tropes, and in works such as Dynamism of a Cyclist (1913) depicted the bicycle as a blurring explosion of modern power. Other Futurists followed his lead. The rider in Fillia’s Bicycle, Fusion of Landscape. Mechanic Idol (1924) is the focal point in a prism of northern Italian landscapes – rows of poplar trees, a church tower – as if he is sucking them into the churning vortex of his wheels. In Gerardo Dottori’s Cyclist, a watercolour of 1916, the rider moves so fast he fragments into the Lombardy countryside.

Like Boccioni, Fortunato Depero designed posters for an Italian bicycle manufacturer – Bianchi, the Ferrari of racing cycles. There is no glance to fin de siècle Paris in his work, however. It is strikingly aggressive, the rider and his wheels emitting the spiky angularity of a bomb blast. In the artist’s Multiplied Cyclist (1922), the dark-clad rider travels at such velocity he leaves images of himself behind like sloughed skin. Vittorio Corona’s Study for Dynamism (1926), meanwhile, seems almost prophetic, his thundering cyclist resembling the aerodynamically helmeted skinsuit-wearing Olympians of the 21st century. Only Mario Sironi adopts a more sombre, less frenetic tone. The Cyclist (1916) shows a lone, pale-limbed rider in a striped woollen jersey struggling towards a forbidding city beneath a glowering sky, like some suffering penitent. It is a counterpoint to the work of Metzinger, Boccioni and the rest – a depiction of the draining effort of racing. Sironi’s rider has, in cycling parlance, ‘hit the wall’ – burned every last gram of energy, exhausted his second wind. A bicycle is, after all, a machine with a human engine of muscle, lungs and heart. It is fuelled by food, oxygen and, ultimately, pain.

By the 1930s the bicycle had lost its novelty and been surpassed by automobile, motorcycle and aeroplane when it came to speed and power. The Futurists quite literally moved on. Bike racing remained – and remains – massively popular, but images of races by contemporary artists gradually disappeared and the bicycle came to be seen less as a symbol of progressive modernity than of bourgeoisie cosiness (exemplified by Fernand Léger’s picnicking middle-class cycling families and the assemblage of roly-poly characters in Peter Blake’s poster for the London to Brighton run in 1985), or of a particular kind of studied eccentricity (Bas Jan Ader falling off his bike into an Amsterdam canal, or an acid-tripping Rodney Graham circling Berlin’s Tiergarten on a Fischer Original).

For Maurice de Vlaminck the tingling thrill of racing would last forever. ‘Never, anywhere,’ the artist wrote in his memoirs, ‘have I felt such utter and complete satisfaction as I did […] when I was nothing more than the winner of a simple bicycle race.’ Roads would be an enduring feature of his paintings, a legacy of those first days of freedom beneath wide skies, the highway (sometimes cobbled like the route to Roubaix) stretching across the canvas and over the horizon, heading, perhaps, towards a distant finish line and the acclamation of an excited crowd.

From the October 2020 issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here