It was not just on the battlefield that France and Britain competed throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1671 the Hôtel des Invalides was established by Louis XIV to show not only his gratitude to the disabled and retired soldiers who had fought in his wars but also his wealth and power. In 1692 in Britain the Chelsea Hospital was created in imitation, but on a smaller scale. The British navy, however, was something the French could not match and it was decided to show how valued the sea force was by creating a similar institution for naval veterans in Greenwich. The first foundation stone of the Royal Hospital for Seamen was laid in 1696 but the complex, designed by Christopher Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor, was not completed until 1751. The elegant buildings were decorated by notable artists such as Sir James Thornhill, whose magnificent baroque decorations in what was initially used as the dining hall soon attracted admiring visitors. (The pensioners themselves thereafter ate in the undercroft.)

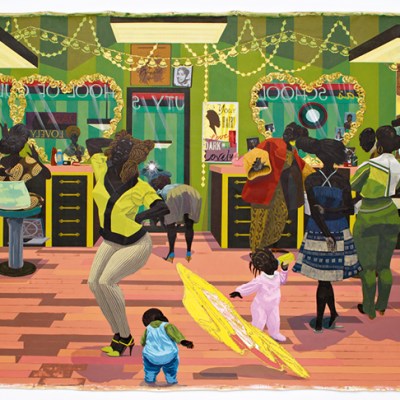

From 1705 pensioners who were too old, ill or disabled to cope were admitted to the Hospital. Others, especially those with wives and families, decided to live outside and received a pension; some of these out-pensioners moved in towards the end of their lives. Among the few thousands who benefitted from this institution were a number of Black sailors. Now an exhibition in the Visitor Centre, located in what was originally the Hospital, tells part of the life stories of some of those Black pensioners, whose presence in Greenwich can be traced in text, images and objects. A small selection of these materials is displayed in the exhibition alongside reproductions of other sources – such as a painting by Andrew Morton from 1845, which depicts a group of visitors to Thornhill’s Painted Hall and includes a Black Greenwich pensioner identified as John Deman from Nevis. There is also, in a space beneath the exhibition gallery, a recreation of the kind of bedrooms or ‘cabins’ that the pensioners would have occupied.

The United Service (1845), Andrew Morton. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

As the exhibition’s curator S.I. Martin notes, this is just the beginning of the journey to uncover the full contribution of Black sailors to naval history. The main problem is that in official documents sailors were usually identified only by their country of origin. Between 1839 and 1853 separate lists of ‘Negro Pensioners’ were kept but before then it is more difficult to identify Black sailors: such information often comes from external sources like parish records or newspaper items.

The sailors were not enslaved: the Navy set its face firmly against slaves on board ship. All the crew shared equally in the dangers and rewards, like prize money and medals, and were entitled to receive benefits from the Hospital. This made the British Navy a route to freedom for fugitives: the demand for sailors was so great that they would not be handed back. Among the sailors and pensioners who took advantage of this and who are mentioned in the exhibition are Briton Hammon, who in 1760 became the first Black North American to publish an autobiography; two others from North America; two from Jamaica; another from Barbados; and even one from the Dutch colony of Surinam (today’s Republic of Suriname).

An illustration published on 25 March 1865 in the Illustrated London News, depicting pensioners entering the West Dining Hall in the Undercroft of the King William Building at Greenwich Hospital. Photo (detail): Ardon Bar-Hama

As well as those whose careers are partially summarised here there are other fragmentary references, such as newspaper reports and inquests, that attest to the presence of out-pensioners and other Black people in Greenwich. A section titled ‘Greenwich and the Slave Trade’ looks at links to the slave trade, such as merchants and investors who profited from it, and lists Black people included in parish and other records. This regrettably perpetuates the belief that some Black people in Britain were enslaved. There was, before the 1772 Mansfield Judgement, some ambiguity about status and this should be admitted, especially in an exhibition of this nature.

There is still plenty to learn here, even if – with the exception of a group of possessions, including a pistol and a watercolour portrait, loaned from the descendants of the pensioner John Simmonds – the paucity of original portraits, documents and artefacts means this is inevitably a ‘book on a wall’: a display of texts and copies of documents and images. The stories that it contains mean this modest exhibition should not be missed by those visiting Greenwich. It is a reminder that, as we pass through the grounds and the buildings of the Old Royal Naval College, we are following in the footsteps of Deman, Hammon, Simmons and other, yet-to-be-discovered, Black pensioners.

‘Black Greenwich Pensioners: Uncovering the History of Black British Mariners’ is at the Old Royal Naval College, Greenwich, until 21 February 2021.