The South African artist William Kentridge works in many media and is in demand around the world as a director of plays and operas. But, as he explains to Apollo, everything begins with printmaking

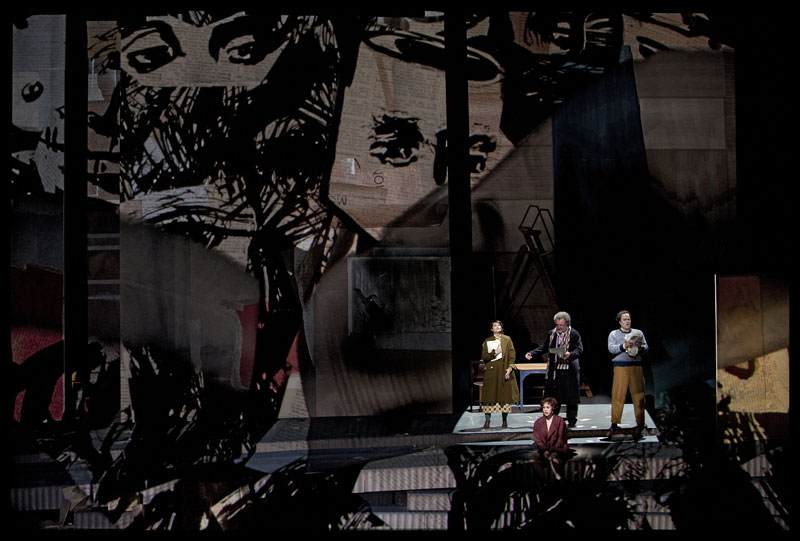

Today, I am in the dark, in the auditorium of The Muziektheater in Amsterdam, home of the Dutch National Opera. The South African artist William Kentridge is directing the first full dress rehearsal of Alban Berg’s opera, Lulu, a co-production with The Metropolitan Opera, New York and English National Opera, London. While Lulu behaves badly in a series of brightly lit sets denoting her various homes – running through husbands, borrowing their clothes, unable to fulfil her lovers’ obsessions or find in them what she is seeking – Kentridge’s team project on to the stage an evolving series of black drawings, lined with thick paint, and sequences of old and new film footage. Drawn portraits of Lulu or her husbands fall apart; sumptuous bunches of flowers disintegrate; text and buildings are projected and then disappear, and there is black-and-white movie footage, as if from the days of silent cinema, of Lulu in prison for the murder of her third husband, and then contracting cholera. These crude, unstable, insistent, monochrome images point beyond the stylish scenery and colour-coordinated costumes, to the fragilities and obsessions that drive the plot to its tragic conclusion. ‘One has to think of the black ink as blood,’ Kentridge explains to his team, ‘and the brush mark as a dagger stroke.’

Kentridge is an artist of black and white, a printmaker first, who uses drawing, animation, film, theatre, sculpture, opera, and even tapestry, to make compelling works that interrogate some of the darkest corners of history and the human psyche. Born in Johannesburg in 1955, the son of prominent anti-apartheid lawyers, Kentridge has, over the last 15 years, become one of the most highly regarded contemporary artists in the world. He has exhibited internationally, and is in as much demand as a director of theatre and opera as a maker of the immersive installations for which he is best known. His many prizes include the Oskar Kokoschka Award, Vienna (2008) and the Kyoto Prize for Art and Philosophy (2010), and this year he was made an Honorary Academician of the Royal Academy of Art.

Scene from ‘Lulu’ by Alban Berg (1885-1935), staged by William Kentridge and performed by the Dutch National Opera, for the Holland Festival in Amsterdam, June 2015. Courtesy Dutch National Opera: Photo © Clarchen and Matthias Baus

In a break between rehearsals, Kentridge comes to find me, dressed in what has become his uniform of a white, cuffed (but tieless) button-down shirt and black trousers. His wide domed forehead and grey hair, and gold pince nez, are immediately recognisable from his films, where he sometimes appears, either alone or interrogating himself, and other artworks. He explains that he is in the last 10 days of what has been a three-year project, when ‘everything comes together and speeds up’. At first, Kentridge turned down the job. ‘And then,’ he says, ‘several months later, looking at an exhibition of German expressionist woodcuts, I understood the language in which the opera could be thought of. Once I had that, then the opera became possible.’ He goes on to say, ‘In a way, there has to be a meeting of a formal language or material – knowing that it has to be ink and paper, or charcoal, or torn paper, or sculpture – with some thematic element of the project which is interesting. So that has to do with instability and desire, with the pictures shattering and reconvening – all of which is both in the music and the story. Out of the form has to come the meaning and the interpretation, not the other way around.’

Kentridge became a printmaker almost by accident. Descended from Lithuanian Jews who had fled the pogroms of the 1880s, his parents were prominent anti-apartheid lawyers. His father, Sir Sydney Kentridge, defended Nelson Mandela in the Treason Trials of 1956–61, and represented the family of Steve Biko, founder of the Black Consciousness Movement, who died in police custody in 1977. Kentridge says, ‘There were always family friends who were artists, so the idea of working in an artist’s studio, as a real activity that people did, was not foreign.’ The family house in a leafy Johannesburg suburb, where Kentridge still lives, was full of art – mostly fine reproductions of masterpieces by Cézanne, Matisse, Miro and Modigliani. ‘Certainly,’ he says, ‘there are questions of ambiguity of mark and transformations of paint into the world…that I remember being intrigued by – not knowing whether the streak of paint is a person or a ditch.’

Kentridge read politics and African history – preoccupations that have continued to feed his work ever since – at Witwatersrand University, in Johannesburg. He then went to art school, where, he explains, ‘To be an artist was to paint with oil on canvas.’ Drawing was merely ancillary. ‘Cackhanded,’ as he puts it, ‘with colour,’ and demoralised, he took an evening class in etching. ‘It felt fantastic,’ Kentridge recalls. ‘It let me think, okay, there is a way of being an artist in which colour doesn’t have to be the starting point.’ Through etching he discovered the whole history of printmaking and the first, largely black and white, century of photography. ‘Series of drawings come out of prints and sometimes even theatre projects come out of prints,’ he explains. ‘As does this Lulu production, since what predates it are the linocuts, as a way of thinking before the production began.’ He adds, ‘There is also a way of thinking of an etching as an extraordinarily, ridiculously complicated form of animation, different states of the plate, when you know that you will rework them.’ For Kentridge these mediums are not value free: he reminds me, for instance, that linocut is the tool of the disenfranchised in Africa. Its lineage goes back to Swedish Lutheran missionaries in Rorke’s Drift, Natal, in the 1960s and 1970s, who taught printmaking under the influence of German expressionism, which in turn drew its inspiration from African masks. One chapter, as Kentridge describes it, in ‘the calamitous history of colonialism’.

Early on in his career, however, there was a hiatus, when Kentridge ceased to call himself an artist. In 1981 he went off to Paris to study theatre with Jacques Lecoq, whose emphasis, Kentridge says, ‘is on meaning before words, everything else that makes meaning’. This experience also set the pattern for collaborative making that has been Kentridge’s mode ever since – whether with printers, dancers, poets, composers, or his video production team. A brief stint in the film industry followed before Kentridge gradually found his way back into art, reusing all the skills he had learned. His intuitive approach to directing is a direct legacy of Lecoq. Kentridge describes, for instance, a breakthrough achieved just that morning in rehearsal: ‘We have had a character on stage and I have not known quite who he is or what he is for. He is an actor, not called for in the musical score. We have slowly found that his attribute when he is on stage is always to be connected to objects – bringing on a drinks trolley, having a newspaper in his hand. Well, there are a lot of deaths in this opera – and it suddenly struck me that among all the things this man is passing, he will now be passing to all the singers the weapons of their own death, which makes him like the figure of death, in the danses macabres.’

In the nearby EYE Film Institute in Amsterdam, Kentridge has an exhibition running until the end of August. It features another new work, which is also a kind of dance of death. More Sweetly Play the Dance (2015) is an imposing installation of large screens on to which a procession of silhouetted figures is projected; the background is the roughly charcoal-drawn bleak landscape around Johannesburg, with grey clouds sweeping overhead. A combination of drawn, cut-out figures and live actors, this pageant presents us with a band and church choir, prisoners carrying their own cages, figures carrying stencilled cut-outs of heroes or saints’ attributes, but also baths and typewriters, two floats of jiggling cartoon skeletons, floats pulled by labourers carrying local politicians and stenographers, and a troupe of Ebola victims trailing drips. They all process behind a figure who tears the pages from a book and are followed by a sole female dancer with a gun. ‘We are re-staging the procession of Plato’s figures in the cave,’ Kentridge notes in the catalogue. What we see is all humanity trudging behind worn-out creeds, bearing the costs of idealism, but also enduring, singing and dancing. As Kentridge says, ‘There is something utopian always about dance,’ even, terrifyingly, when the dancer carries a gun. While this work can clearly be read as an allegory of South Africa, it also resonates with Imperial parades, Saints’ Days and carnival processions across the world, political rallies and the despairing lines of refugees displaced by war, throughout the centuries.

The imagery of More Sweetly Play the Dance is linked with other Kentridge projects currently underway in Rome and Beijing. And this sense of the universal arising out of makeshift improvisations in a studio in Johannesburg is at the core of Kentridge’s achievement. The Refusal of Time (2012), a five-channel video and sculpture installation for Documenta 13 that premiered in a grimy railway shed in Kassel, was a hectic meditation on the measurement of time and relativity and the imposition of Western science and regulatory systems in non-Western cultures. It has been shown all over the world and is now owned jointly by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Kentridge says that his theatre production, Ubu and the Truth Commission (1996/97), which he co-directed with the writer Jane Taylor, was created specifically in response to the post-apartheid process of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: ‘Wherever we have taken it people have said, well I don’t know how people in the rest of Europe will understand it. But in Germany it is perfect, because it is about the Stasi in East Berlin, and then we did it in Columbia in Bogota and they said, well I don’t know if it makes sense anywhere else, but for us it is all about our negotiations with the FARC rebels…so in that sense, it has not a universalism but an ongoing specifically local reference, that echoes with very particular, but similar circumstances.’

Perhaps one clue to Kentridge’s appeal today is that, as suggested by his triptych of large-scale screen prints entitled Art in a State of Grace, Art in a State of Hope and Art in a State of Siege (1988), he makes work for our besieged times. ‘I never thought of them as setting an agenda for the next 30 years of work. But in some ways they have and they did.’ He continues, ‘Art in the State of Hope referred to the political art of the constructivists, of the early Soviet era, where art and utopian thinking would sit comfortably together. Art in a State of Grace was art retiring from the world into a condition of beauty, if you think of the Matisse cut-outs, and those gorgeous paintings done during the Second World War. That was another kind of thing, which I longed for, but which was impossible.’ Instead, born into the last violent phase of colonial power in South Africa, he has devised an Art of the State of Siege, ‘where all the ambiguities and uncertainties are present, but it is not a retreat from the world nor a triumphalist confidence in the way the world will unfold.’ Certainty, as he sometimes remarks, leads only to the Killing Fields of Pol Pot.

His new project for the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Notes Towards a Model Opera, part of a retrospective which runs until 30 August, was inspired by the footage of the propagandising Model Operas Madame Mao created during the Cultural Revolution. For Kentridge, this episode provoked comparisons with other upheavals – student riots in Paris in 1968, the Paris Commune in 1871 – and with his regret in 1968 ‘that I had been born five years too late in the wrong country. If I had been five years older, I could have been part of the student protests in America or Paris, that’s where real life was and somehow life had passed me by – which is a sense of being stuck in the colonies, on the periphery, in Johannesburg.’

Yet it is in his studio, in Johannesburg, that all the influences he has absorbed, from Dürer and Rembrandt to Goya, to Gogol to Alfred Jarry to Picasso and Dada and Mayakovsky, from philosophy and politics to art history, find their way through drawing and back out into the world. This is where, as Kentridge puts it, ‘The theme and the image come together, where the world meets the act of drawing halfway.’ This is also where the characters who people his projects – the greedy capitalist Soho Eckstein, his lovesick alter ego Felix Teitelbaum, Ubu the absurd potentate, the old-fashioned typewriter, the giant megaphone, the nose from Gogol – have their birth. Invented for one-off use in specific works, these characters, human and inanimate, ‘now function like Commedia dell’arte – they can be pulled out of the cupboard and perform whatever role, they can inhabit whatever film I want to make.’ Kentridge adds, ‘They are a vector through which the world can be looked at.’

Plato’s allegory of the prisoners in the cave is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the text that continues to inspire all of Kentridge’s work. As he said in the first of his 2011–12 Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, Six Drawing Lessons, ‘The questions it provokes, its metaphors, are the pivotal axes of questions both political and aesthetic.’ After all, it is largely in the dark that his works unfold – in theatres and blacked-out galleries – with films and animations flickering urgently on the wall. Plato sees the fools in the cave, watching the shadows cast by people passing above, as deluded and in need of the enlightenment that can only be provided by philosophy. Kentridge, however, trusts his monochrome images, and our imaginative capacity to piece together the truth from them. And once in front of them, it is hard to move away, to go back into the light, so compelling are the truths half-glimpsed in those shadows and communicated with such invention, wit and compassion.

‘William Kentridge – If We Ever Get to Heaven’, is at the EYE Filmmuseum, Amsterdam until 30 August 2015.