Looking at the recent works by Berlinde De Bruyckere currently on display at Hauser & Wirth Somerset (until 1 January 2019) is something akin to looking at the cross-section of an archaeological trench. Every piece in her two new series, Courtyard Tales (2017–18) and Anderlecht (2018), is formed from the careful accretion of layered materials – aged blankets in the former; stacked animal hides in the latter – that makes literal something that has always been there in De Bruyckere’s work. Hers is an oeuvre in which layering – physical, personal, historical, and art-historical – is all-important. It is something that, even through the tatters of an old blanket, can give her work an almost vertiginous sense of depth.

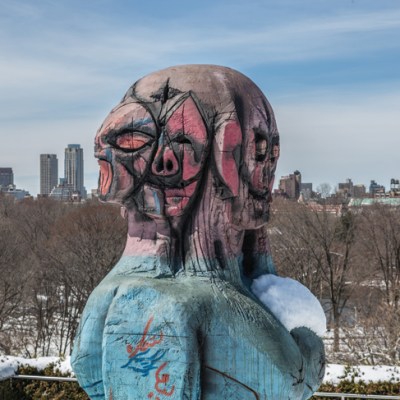

Anderlecht (2018), Berlinde de Bruyckere. Photo: Mirjam Devriendt, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Berlinde De Bruyckere

Born in 1964 in Ghent, De Bruyckere has built her career on work profoundly indebted to a long and local lineage of Old Master painters, to Christian iconography, and to classical mythology, translated through her personal history into a distinctively corporeal corpus. Working with animal skins and wax sculptures based on casts taken from human bodies, her work since the early 2000s has been concerned above all with the body and its flesh caught in a ‘moment of pain’ that reaches across and collapses the layers of history into a three-dimensional instant. As in myriad Renaissance martyrdoms, it is a moment that – in shows such as ‘Suture’ (Leopold Museum, Vienna, 2016) and ‘The Embalmer’ (Kunsthaus Bregenz and Kunstraum Dornbirn, 2015) back to ‘Schmerzensmann’ (Man of Sorrows, Hauser & Wirth, London, 2006) – De Bruyckere has explored as a locked interval of metamorphosis between total suffering and sensuous beauty. In a sculpture like The muffled cry of the unrealizable desire (2009–10), it is possible to trace the ghosts of both Marsyas and Saint Sebastian – tied to their trees and stripped bare for torture. While installing her monumental tree sculpture Kreupelhout (Cripplewood) in the Belgian pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale, she visited 37 different Saint Sebastians in three days, to pay homage to ‘the incarnation of male beauty’ that he represents in his agony.

In the new works at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, however, the body has disappeared, and the layers of history once cast or stitched into limbs and torsos have become more literal. Courtyard Tales and Anderlecht are, in appearance at least, minimalist works a world away from the figuration of the last two decades: the former a series of seven wall-hangings built up out of rotting and tattered blankets; the latter a trio of wax sculptures modelled on industrial pallet stacks of curing animal skins. When I meet De Bruyckere in the gallery’s library, housed in one of the old farm’s converted outbuildings, I ask if the absence of bodies marks a departure. She responds quickly: ‘It’s more a sort of evolution.’

In the case of Courtyard Tales, that evolution started with turning back in De Bruyckere’s own history, to her De Slaapzaal (Dormitory) series from the late 1990s. In those works, she layered blankets several mattress-thicknesses deep on simple single beds, the fabric often carefully pierced with apertures that allow the viewer to see right down to the mattress beneath. She needed, she said, ‘to translate this feeling again, this very intimate space of a bed’ but at the same time to approach it differently, as someone who, with all the work between then and now, ‘can’t imagine making that kind of a work’ again. ‘The layers,’ she says, ‘are like the layers that we all have in our mind, which work like memories. And with memories, very often you forget, and all of a sudden something happens, and it brings you back in your history.’ Once you take control of that, she continues, it becomes possible to say: ‘Okay, now I can jump into this layer and take it, and start from older experience, and add something new.’

Courtyard Tales V (2018), Berlinde de Bruyckere. Photo: Mirjam Devriendt, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Berlinde De Bruyckere

With Courtyard Tales, that something new is, simultaneously, something old: the body. The blankets, as well as calling up her personal history as an artist, are a proxy for the bodies that so dominated her work after De Slaapzaal. Blankets, De Bruyckere notes, ‘are the closest thing to your body, even closer than clothes. After a season, you throw clothes away, but the blanket on your bed stays there forever […] [The bed is] the place where you make love, where you give birth, where you have children, where you die, even where you have the material you use to give first aid when there is an accident in the street.’ It is important, therefore, that the blankets are objects that have absorbed such events. Sourced from charity and second-hand shops, all of De Bruyckere’s blankets have, as she sees it, lived. ‘Because of that,’ she says, ‘you feel the body even not seeing the body.’

That sense of the body’s absent presence inflects the entire process behind the Courtyard Tales. Having become, in some sense, bodies, De Bruyckere’s blankets also begin to age and suffer as bodies. The fabric that has made its way into the finished hangings has been systematically aged over the course of one to two years. Hung on frames in a courtyard of her studio in Ghent, sometimes partially buried, they have been bleached, rotted, and eaten away by sun, rain, and animals. Where in De Slaapzaal the blankets were pristine, and her inventions direct and controlled, the blankets in Courtyard Tales are altered by ‘nature and time’. ‘It’s a really beautiful thing that happens,’ she says, ‘to put them outside […] to create that feeling of a blanket that will fall apart, that will weaken’, aging in different ways with each season, but in the end retaining its integrity.

Once cleaned, the aged fabrics were pinned to the wall, and layered up in a process that she likens to ‘making a painting, much more than a sculpture’: choosing which blankets will go over which, just as a painter might build up washes of colour. In the process, De Bruyckere explains, they became portraits, and once again called back to the Old Masters and the old martyrs. ‘The moment I took the decision to nail the blankets on the wall, I immediately got the feeling of the nails in the cross, that you had nailed a body on the wall, even though it was just a rotten blanket.’ Finally, ‘the blanket became so vulnerable and fragile [that] it was showing the same weakness as a wounded body’ – and by extension, similar forms of beauty.

De Bruyckere admits – and relishes – a tension here. While bodies, even in their absence, remain a central source of weight in her work, she says that she has had to go beyond them. When I ask her if she has moved on from her more literal explorations of bodily suffering, she thinks carefully before saying: ‘Maybe. For the moment, I think so. The body at the moment is not big enough. […] It can’t translate the feelings or the ideas that I have in mind to talk about.’ Things, she notes, have changed a lot in the last decade, to the point that the body alone is no longer ‘the perfect tool to talk about pain’.

A crucial element of this is the current moment in modern politics. Faced with De Bruyckere’s blanket ‘portraits’, it is hard to escape the refugee crisis and its most prominent images. When looking at the blankets aging on frames in her courtyard she was conscious that ‘that was what I saw on television, of the camps in Calais, and all over the world’. While she resists the impulse to ‘be an illustrator’ of the crisis, as something direct and obvious, the camps form part of the motivation for her move beyond the body. Somatic suffering no longer covers the kinds of pain she sees the need to express: ‘the wounds and marks they will have’ as survivors are no longer physical, but a question of ‘being unrooted’, of having ‘to fill up your life again and start with nothing […] to leave your country.’

Les Deux (2001), Berlinde de Bruyckere. Photo: Richard Max-Tremblay; © DHC/ART Fondation pour l’art contemporain

It is something she has explored in more literal forms before – above all in the uprooted elm of Kreupelhout – and constitutes another layering within her own corpus. Here, however, there is a shift that gives De Bruyckere herself pause to think. Despite its fixation on suffering, De Bruyckere’s work through the early 2000s made clear its art-historical affiliations with a faith in change for the good. ‘All the years before,’ she says, ‘when I was talking about my work and about even the works dealing with pain and anger and fear, I was trying to use materials that were very fragile or beautiful, to put into them some hope or beauty. […] I wanted to raise the goal that people could hope, even when they look at a wounded body or a wounded tree, or hanging horse, that there was something beautiful inside.’ Looking at pieces like the horses of Les Deux (2001) or We are all flesh (2012), with this in mind people might ‘start a dialogue or discussion with the work or each other, talking about feelings we don’t have the words for’. Even within the bleakness of looking at death, De Bruyckere says, ‘To give hope was one of my major wishes.’

Pietà (2007–08), Berlinde de Bruyckere. hoto: Mirjam Devriendt, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Berlinde De Bruyckere

Now, by contrast, in light of a political situation that seems, on many fronts, quite starkly desperate, she does not know if her work continues to offer such hope. It is, she says ‘very confronting’, to look at her own work and see for the first time, ‘very little hope’. This is perhaps clearest in the Anderlecht trio. Moulded from stacks of hides, cured in salt at a tannery near her studio, the subtly coloured wax of the sculptures is all at once deathly grey, fleshly, and icily marmoreal. When I ask if the ‘hides’ form a contrast to the blankets in being caught in the middle of a process that tends towards usage, and even resurrection of a kind, she shakes her head. ‘For me, they are arrested at that point. They look like they are frozen, or stitched on to each other, like they can’t be removed.’ The same fixity, De Bruyckere suggests, goes for all of us in the current political moment.

Crucial, too, is the journey that the skins have made in order to be arrested at this moment of stacking and curing: from living individuals to a single mass. ‘The mass,’ she says, ‘is so heavy to carry, and to carry mentally. It’s not just one death, it’s an enormous amount of death.’ This is something we are accustomed to accepting not just with animals, but with humans too. ‘When you die in a war, you become an anonymous person, because so many people die during a war, but for your family, for your wife, you are still who you are. And now, putting all these layers on top of each other, for me, it becomes a metaphor for death and anonymity.’

She is surprised by the bleak fixity of the new works. ‘Now when all these works are finished, and when they are hanging, it’s the first time that I see it, so I also have to deal with it and to feel what will be the next stop.’ Lack of hope, though, is not the same thing as lack of inspiration. Looking forward to her exhibition ‘It almost seemed a lily’ (Museum Hof van Busleyden, Mechelen, 15 December–12 May 2019), it is clear that the last two years have been a creatively productive time for her. The works for Mechelen return to the medieval and early modern Christian inspirations that ran through her figurative work, drawing on newly restored horti conclusi (‘enclosed gardens’), a form of devotional sculpture that she first encountered in Leuven in 2016. The horti, made in Mechelen, are astonishingly detailed objects of private worship from the early 16th century: sculptures of the Virgin Mary enclosed in cabinets overrun with miniature handmade flora and fauna, above all lilies. De Bruyckere says that their impact on her was instantaneous, ‘so big that you immediately have the idea to translate it, and to create new work, and a new topic around that experience’. It was ‘a whole world opening’.

It almost seemed a lily IV (2017), Berlinde de Bruyckere. Photo: Mirjam Devriendt, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Berlinde De Bruyckere

Inspiration from the horti conclusi gave her, she says, ‘the courage’ to work with the lily and with its symbolism in Christianity for the first time, and in doing so to experiment with enlargements of scale – something she has always previously avoided in her work. She is quick to note, though, that as she worked on the Mechelen sculptures concurrently with the Courtyard Tales and Anderlecht pieces, they partake of the same worry over the future, and the same sense of hopelessness. Where the horti conclusi hold out their miniature lilies as tokens of a more perfect world, hers, enlarged, cast in wax like the Anderlecht works, and hung limply over aging wallpaper in wooden frames, are ‘the lily in decay’, lilies ‘at the moment when they’re gone’, and when there is ‘no possibility of new life’.

Yet De Bruyckere herself is not without hope; there remains a core of possibility in her work. Recalling being sent to boarding school at five years old – an experience still visible in her interest in dormitories, blankets, and comfort – she says that loneliness is something she is always aware of, but not afraid of. ‘I learned to deal with that. The loneliness was always there […] I was there on my own, and the way to escape from that loneliness was to make your own drawings and create your own world.’ Not everyone can do that, but perhaps enough of those who are uprooted in the current crisis do, so that something positive will come of it. ‘We have now this mix with all these cultures, and I’m sure that it will reach us and feed us. And that’s the future, so we don’t have to be afraid of that.’

‘Berlinde de Bruyckere: Stages and Tales’ is at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Bruton, until 1 January 2019. ‘It almost seemed a lily’ is at Museum Hof van Busleyden, Mechelen, from 15 December–12 May 2019.

From the November 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.