From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

How will you contain your excitement as you wait for the opening of the exhibition ‘Vanessa Bell & Duncan Grant’, recently announced for November 2026 at Tate Britain? With more than 250 works, the show promises to take in ‘vivid portraits, still lives, landscape paintings, decorative works on furniture, ceramics, textiles, and much more’. And it also includes what the press release calls an ‘unmissable highlight’: ‘a once in-a-lifetime restaging of Duncan Grant’s studio, relocated for the exhibition from their Sussex home, Charleston’.

One way to occupy yourself in the meantime would be to read Wendy Hitchmough’s Vanessa Bell: The Life and Art of a Bloomsbury Radical (2025), then go and see ‘Roger Fry’, which opens this month at Charleston – where of course you could see the painted furniture and Grant’s studio in its original location. While you’re there, you could order a reproduction of Bell and Grant’s Famous Women Dinner Service (50 plates for £12,000) and have them delivered in time for Christmas. Then you could cook your guests cucumber vichyssoise from The Bloomsbury Cookbook: Recipes for Life, Love and Art, and they could eat it off a tablecloth made from an Omega workshop fabric design (£85 per metre).

But perhaps you’ve had enough opportunities to look at paintings by Bell and Grant and their Bloomsbury associates? After all, there are hundreds of them in national collections, and the Tate exhibition will come hot on the heels of shows including ‘Vanessa Bell: A World of Form and Colour’ (2024), which opened at MK Gallery and transferred to Charleston, only closing in September; ‘Dora Carrington: Beyond Bloomsbury’ (2024) at Pallant House; ‘Gardening Bohemia: Bloomsbury Women Outdoors’ (2024) at the Garden Museum; and ‘Beyond Bloomsbury: Life, Love and Legacy’ (2021), which opened in Sheffield and then moved to York. And it doesn’t feel like much time has passed since the major retrospective ‘Vanessa Bell: 1879–1961’, which opened at Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2017, and the blockbuster ‘Virginia Woolf: art, life and vision’ (2014) at the National Portrait Gallery.

On the literary front, the tide is likewise unstoppable. There’s practically no aspect of Bloomsbury tastes and mores that hasn’t been mined for the trade non-fiction market. Was Virginia Woolf imaginatively drawn to water and swimming? Olivia Laing has it covered, in To the River. Did she spend a bit of time in the countryside? Here’s Harriet Baker with Rural Hours. Did she live in a square? Francesca Wade is on it, in Square Haunting. Did the Bloomsbury group wear clothes? Charlie Porter’s Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion is where we need to look for the answer. Doubtless an enterprising editor is somewhere commissioning the book on Bloomsbury and walking, the book about the pet cats, dogs and monkeys of Bloomsbury, the group biography about Bloomsbury polyamory, as we speak. Penelope Lively, already experiencing a surfeit of Bloomsbury when writing in the LRB in 1981, had a recommendation for publishers:

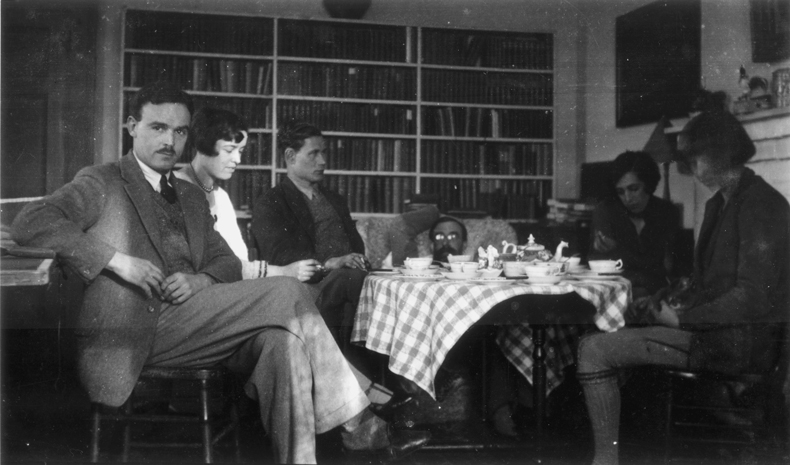

There is one possibly final Bloomsbury book that would be of value, not only to those besotted with the scene, but also to those who get inextricably mixed up about the members of the cast […]: a ‘Who’s Who’. I envisage it providing not only brief biographical details but visual aids: charts that would indicate the state of various relationships at any given point in time […] and for identification purposes a gallery of portraits extracted from the apparently inexhaustible supply of fuzzy photographs of Raymond and Saxon and Maynard and everyone having picnics or sitting in the garden in deckchairs.

It’s not that the art, writing and design of the Bloomsbury group isn’t often wonderful. The exhibitions and books that I mention above continue to show the richness and strangeness of some of the work that came out of this constellation of literary and artistic talents. On the day that I file this piece I’m teaching a seminar for first-year undergraduates on To the Lighthouse, Woolf ’s inexhaustibly brilliant novel of 1927, and it never misses or gets old. Even for students born in the late 2000s, even for students who have just left mainland China for the first time and have absolutely no preconceptions about modernism or English culture, if any work of difficult 20th-century literature is likely to click with them, to make them feel the wonder and delight of a challenging and sophisticated work of art, it’s this one. And the restoration of Vanessa Bell to the status of a major international figure in her own right, along with the recovery of Dora Carrington as a smaller but nonetheless important artist, has been an important critical project.

But doesn’t all this take up a disproportionate amount of cultural space? When I look at the latest unnecessary critical edition of a Woolf novel that has already been edited and annotated dozens of times – or the proliferation of gift-shop reproductions and imitations of Bloomsbury lampshades and curtains; or a broadsheet feature on ‘How to get the Charleston look in your own home’; or the Vogue photographs of Kate Moss lounging on a Charleston sofa, naked but for her cowboy boots and straw hat; or Cara Delevingne wearing Charleston-inspired Burberry on the runway – there’s a part of me that longs for a bracing dose of the hard-edged modernism of Ezra Pound or Wyndham Lewis. It was Lewis who railed ceaselessly against the ‘essential respectability’ of the Omega workshop (a ‘curtain and pincushion factory’) and of what he called ‘a small group of people which is of almost purely eminent Victorian origin, saturated with William Morris prettiness and fervour’. When I look at the interiors at Charleston, every panel and headboard and lampshade papered over or daubed with blowsy watercolours, every surface cluttered with stuff, I dream of white walls, modular bookshelves and tubular steel furniture. Whatever happened to ‘Chuck Out Your Chintz’?

The anti-Bloomsbury arguments are easy to assemble. When Pound abused his hated rivals as the ‘Bloomsbuggers’, or when the midcentury reviewer Keith Roberts famously called Vanessa Bell ‘essentially a lavender talent’, they might have expressed critical reactions stained by homophobia or sexism, but they put their finger on something important about the annoyingness of the Bloomsbury group. More fruitfully, this annoyance has been framed as a justified class-envy. For the Northumbrian modernist poet Basil Bunting, the annoying thing about Bloomsbury was that ‘they were all of that well-to-do middle class, bordering on country gentry who felt that if you couldn’t afford to live in Bloomsbury or Regent’s Park or some similar, desirable, but very expensive part of the world, well, poor devil, there wasn’t much to be expected from you.’

Bunting puts his finger on something crucial here: how the intensity and beauty of the Bloomsbury vision of life was underwritten by the desperate narrowness of its social outlook. Much of the most important recent critical thinking about Bloomsbury, galvanised by Alison Light’s superb Mrs Woolf and the Servants (2007), has been dedicated to confronting the class-obliviousness of the Bloomsbury group.

Resenting posh people is practically a British national pastime, so perhaps one shouldn’t indulge in it too much. But the Bloomsbury group really do invite it. Consider the Dreadnought Hoax of 1910. This is the time when Duncan Grant, Virginia Woolf and others dressed up as the Abyssinian royal family, with robes and turbans, costume jewellery, stick-on beards and black face paint, and tricked their way into a tour of the HMS Dreadnought, convincing the naval officers they were African by saying ‘Bunga bunga!’ to show their admiration for the warship.

Or consider the wealth of evidence in Light’s book about Woolf and her circle’s treatment of and attitudes towards their domestic staff, which veered between fascination, fear, revulsion and co-dependency. For the Bloomsbury group, the ‘servant problem’ meant how to keep them on a short leash and stop them getting too uppity while still getting them to do all the cooking, cleaning and child-rearing for you. When Woolf ’s long-term servant Lottie asked for a pay rise in 1917, her first response was not to consider whether she was being a fair employer but to muse in her diary: ‘The poor have no chance; no manners or self-control to protect themselves with; we have a monopoly of all the generous feelings.’

Of course, it doesn’t matter whether they were snobs or casual racists or whether they treated their servants poorly. They’ve all been dead for decades, and making art and literature has nothing to do with being a morally admirable person. The more important questions are: first, did the self-confessed snobbism, the insularity, the attitude towards the poor, set a limit upon the artistic achievements of Bloomsbury? And second, what are the consequences today of giving such a central position to work that is bound up in so many ways with generational wealth and deference to the tastes and tacit assumptions of the upper-middle classes?

In answer to the first question, I would say that it probably did. Rebecca Birrell’s reading of Bell’s painting of The Kitchen at Charleston (c. 1943), in her book This Dark Country: Women Artists, Still Life and Intimacy in the Early Twentieth Century (2021), suggests how this might have worked:

Grace is in the kitchen, the table laid with vegetables she will go on to wash, chop and cook. Hours of work are ahead of her, but none of the difficulties of those impending tasks are evident, or even hinted at: the surfaces are clean, the crockery unused, her apron and dishcloth unsullied, her unmarked hands hovering over an apparently empty mixing bowl. […] Grace is one domestic object amongst a room of others, her body useful and orderly, her subjectivity entirely collapsed into her labour. […] Yet, for all the eerie disregard that attends the representation of Grace, the image remains one of absolute harmony – a smug kitchen pastoral.

In a study of Bell that is full of loving appreciation for her work and spirit, Birrell is still alert to the exclusions and limits of her imagination. ‘Vanessa was only able to live as she pleased through instrumentalising the labour of other women,’ she writes – and consequently the work itself, the understanding of people and the world that it expresses, is arguably limited by this disregard for the lives of most of the population.

In answer to the second question, I would say that today’s redoubled Bloomsburymania probably is a bit of a backward force in the culture. We had surely already reached peak Bloomsbury in the 2010s, when Sue Limb’s superb BBC Radio 4 sitcom Gloomsbury ran for five series, giving us the adventures of Ginny Fox and Vera SackclothVest in place of Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. By the time the anonymous satirical Twitter account ‘Bougie London Literary Woman’ was launched in 2018, with a detail from Vanessa Bell as its banner image, peak Bloomsbury had been surpassed (‘Giving myself the treat of a pilgrimage to Charleston. If my last visit is reliable indication, by the time I reach the bedrooms I expect to be so overcome with joie de livres that I shall be openly weeping.’). The strength of the parody (later revealed to be written by Imogen West-Knights and an unnamed friend) was that Bougie London Literary Woman was essentially a deadpan recitation of the sway that the soft-bohemianism and upper-middleclass style choices of Bloomsbury still hold in the London literary world. But in the 2020s, we are replaying this Charleston-worship having lost sight of the fact that it was ever a joke. We get new Bloomsbury retrospectives so that we can rediscover things that have never been out of sight for a moment. Can we not just do something else for a while?

From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.