Does anyone get to witness a crisis on this scale through their own eyes? Giovanni Boccaccio witnessed the epidemic of bubonic plague that came to Florence in 1348 – his father and stepmother were among the ‘multitude of corpses’ he described in the introduction to The Decameron, ‘stowed tier on tier like ship’s cargo’ in vast trenches. He described things he ‘would scarcely dare to believe, let alone write’ if he had not seen them himself. But he also seems to have plucked several of his details from a book written half a millennium before, about an epidemic two centuries before that. The exodus of those who thought they could outrun the scourge; the emptiness of houses once filled with nobles and retainers; the abandonment of sick children by terrified parents… according to Paulus Diaconus, these all happened in the plague’s first sally on Europe, in the age of Justinian.

Perhaps history was repeating itself; perhaps Boccaccio was repeating history. Scholars could argue it both ways, but having watched the world scramble to find precedents for Covid-19, I can see why Boccaccio might have wanted Paulus’s History of the Langobards to hand, just to check he was not going crazy. None of the precedents exhumed this spring – Aids, Spanish Flu, the Black Death itself – quite fits, but they have all left their mark on news coverage, on conversations with friends, and on our actions.

I have had the sense, often, that the media, like the rest of us, has been trying to tick off an epidemic checklist by reference to old sources. Boccaccio and the Black Death have been doing the rounds, of course. Here in London, when lockdown became inevitable, plenty of those who could left, like Boccaccio’s ten storytellers in The Decameron, who retreat from Florence, for quiet places in the country. The BBC, meanwhile, reported local authorities in Wales, Scotland and Cornwall begging city-dwellers not to spread the virus by fleeing their way. Hart Island, New York, a still-functioning potter’s field for the state’s poor, has appeared in various outlets as a ‘mass grave site’ – complete with drone footage of coffins being stacked like cargo crates in carved fosses.

Decameron (1837), Franz Xaver Winterhalter. The Princely Collections, Liechtenstein, Vaduz-Vienna Photo: Artefact/Alamy Stock Photo

Boccaccio’s illustrators do not dwell much on the horror that frames The Decameron. Nor, for that matter, does Boccaccio himself: once he has gathered his brigata in the church of Santa Maria Novella, he swiftly gets them out of the city to a series of secluded loci amoeni. In each they are safe and sound, waited on hand and foot. Perhaps the most famous picture of them all, Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s Decameron (1837) shows nine youths intently listening to that day’s storyteller, lounging by a fountain, every one smiling demurely. After ten days of stories they slip back into normality. The ladies ‘returned to their homes’; the young men ‘went off in search of other diversions’. It is an interlude.

The thought of the brigata in their country manor, their walled garden, and the paradisiacal valley of the ladies does not speak much to me. What comes to mind instead is what hovers for the most part outside the text and its illustrations: the thought of the city they leave behind. Before they decide to depart, the youths’ main complaint – more than the risk of death – is the indecorousness of it all. The natural leader of the group, Pampinea, complains about criminal exiles returning and ‘careering wildly about the streets’, and ‘the scum of the city […] prancing and bustling all over the place, singing bawdy songs’, while others shout ‘“So-and-so’s dead” and “So-and-so’s dying”’. She wants to go where she can hear ‘the birds singing’.

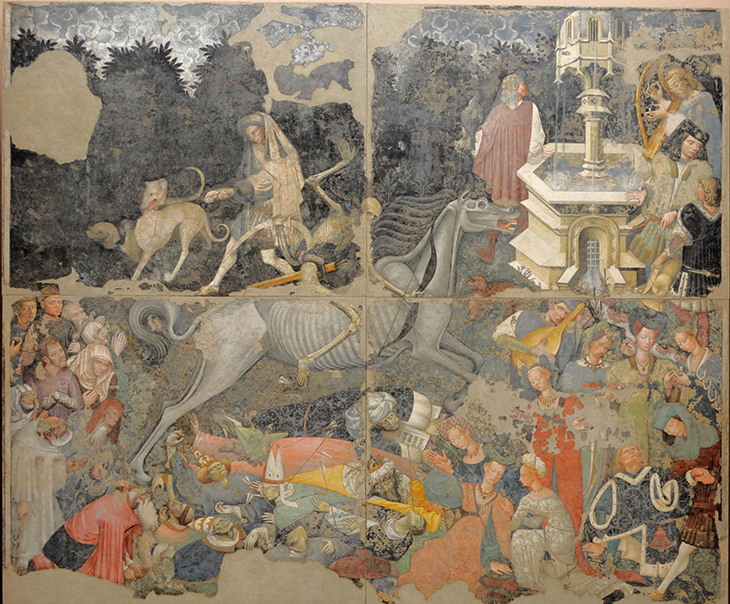

The Triumph of Death (c. 1446), artist unknown. Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo. Photo: Abbus Acastra/Alamy Stock Photo

You can see the noise of plague in its paintings. In the mid 15th-century Triumph of Death, now in Palermo’s Palazzo Abatellis, Death gallops his skeletal horse across a society in tumult, trampling its inhabitants, firing plague arrows into everyone he sees. Down in the bottom-right corner, directly in Death’s firing line, is a group that could even be Boccaccio’s brigata: seven young women and three young men, nobly dressed, huddled together, heads turned away, attempting to wait it all out. Several of them have already been peppered with Death’s darts. The fresco’s composition and decomposition both lend weight to the sense that the world is shattering around the white rider. With its praying masses, musicians, and growling dogs, the whole thing is mutely cacophonous. So too is Poussin’s Plague of Ashdod – painted in 1630, when the plague was once again stalking Europe – in which the built environment maintains its calm perspective, while its inhabitants dash to and fro, weeping, moaning, dying.

That, though, is a difference between Boccaccio and Paulus. Paulus’s plague brought emptiness and silence: where it travelled, he wrote, ‘You might see the world brought back to its ancient silence.’ London might not be empty or silent, but it is emptier, quieter. The background hum has gone. From the development going up half a mile from my flat in Bermondsey, every sound echoes out singly from workmen who, obeying the two-metre rule, are picked out against the sky like statues of the evangelists on Italian churches. Walk through the centre of the city on a weekday, and it looks not like The Plague at Ashdod but the eerie 16th-century Florentine view of the Ideal City in the Walters Art Museum: a few stragglers picking their way through an environment impervious to human frailty. And, as everyone keeps saying, you can hear the birds singing.

From the June 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.