First, the frieze. Triumphal France is not the kind of work you expect to see in a new museum. A circular marouflaged canvas painted for the Exposition Universelle of 1889 and celebrating colonialism, it shadows the entire Bourse de Commerce, a new museum helmed by French luxury-goods billionaire François Pinault. It shades the galleries on the third floor and interrupts the collection with glimpses of a worldview now considered exploitative: naked Native Americans greet a crisply dressed European, a Black woman holds up a parasol for a white woman.

The Bourse wasn’t Pinault’s first choice to show off his collection. The original plan was a museum designed by Japanese architect Tadao Ando on an island close to Paris. But that years-long project never got off the ground. ‘I don’t want to put anyone on trial here,’ Pinault wrote in 2005 in a Le Monde editorial, yet the reasons were clear. Bureaucratic hurdles had made the project impossible. Instead, he opened two museums in Venice and hatched a new plan: to take over the Bourse, a former grain-trading floor and stock exchange, and commission a redesign by Ando. After delays due to construction (expected) and coronavirus (unexpected), the museum opened this May. I smiled when I received the invitation to the press launch: 18 May, the day before Paris – museums included – was legally allowed to reopen. Evidently there was no time to waste.

Central to Ando’s renovation of the Bourse is a concrete orb lining the building’s central rotunda, effectively closing off the open floor to create a contemplative space. In the middle of the room twists a replica of Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine Women by Urs Fischer; around it sit replicas of chairs, including several from the Musée du Quai Branly. Unlike the originals, these figures, which build on a display at the 2011 Venice Biennale, are made of wax and filled with wicks. They’ll burn away over the course of the six-month exhibition, ‘Opening’ (until 31 December). During my first visit, the waxen figures were striving towards the building’s impressive cast-iron roof. By the time I returned a week later, the wax had already begun to drip in long stalactites; one of the chairs had wrinkled in half. The effect is as creepy as it is frightening; who knew you could tame fire that way?

Untitled (2011) by Urs Fischer installed min the rotunda of the Bourse de Commerce, Paris. Photo: Stefan Altenburger; courtesy Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich; © Urs Fischer

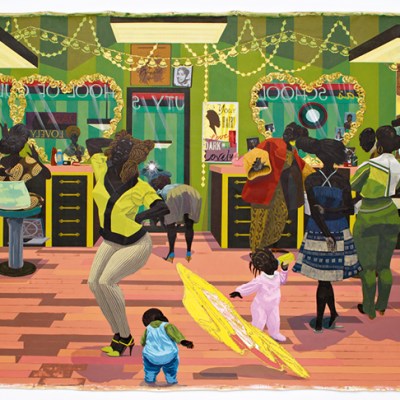

But back to the frieze. ‘This exhibition has been conceived as a manifesto of the values I have always championed – the thirst for freedom, the rebuttal of injustice, the acceptance of diversity,’ writes Pinault in the introduction to the catalogue. Curator Caroline Bourgeois’s gambit is a bold one: to contrast the history displayed on the frieze – which was renovated for the reopening – with art made by artists of colour. A gallery on the ground floor is filled with the work of David Hammons, who uses found objects – street signs, bike parts, taxidermised cats, sometimes his own body – to comment on cities, music and African-American life in the United States. The second floor features work by Kerry James Marshall that, museum text explains, seeks to rethink the place of the Black body in portrait painting. (While undoubtedly true, reducing the work of one of today’s best living painters to a commentary on race alone strikes me as a narrow reading.)

Responding to French history with American artists may be a missed opportunity. Where are the French artists whose art responds to colonialism, or the West African artists such as Julien Sinzogan, with his monumental panoramas of slave ships, or Romuald Hazoumè, whose sculptures, made from petrol cans and glass bottles, respond to the specific French-African history of exploitation?

(From left) Untitled (Franz West) (2011), Untitled (Paula) (2012) and Untitled (Ernst Ludwig Kirchner) (2010) by Rudolf Stingel installed at the Bourse de Commerce, Paris. Photo: Aurélien Mole; courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York; © Rudolf Stingel

Another focal point is cultural appropriation. Seeking insights into a collector from his art is a risky exercise, but it doesn’t surprise me that appropriation would be of critical interest to a leader in an industry whose success is contingent on distinguishing luxury from knockoffs. The Italian artist Rudolf Stingel repaints photographs, blowing up images and their imperfections to an exaggerated scale. His portrait of Austrian artist Franz West takes up an entire wall; paint lines show the damage to the paper. A gallery on the first floor devotes a section to Sherrie Levine, who shocked the art world in the 1980s by claiming photographs by Walker Evans as her own. Here, we see her reworkings of photographs by August Sander and Russell Lee. (Is it a play on cultural appropriation to tell the same joke more than once?) I prefer Louise Lawler’s work a few walls down in the same gallery. Helms Amendment (1989) takes on that legislation, which outlawed the use of funds from the Centers for Disease Control for AIDS education or prevention. On the wall are photographs of cups belonging to senators who voted in favour of the bill. One belongs to then-senator Joseph R. Biden.

The displays are frugal on explanations; labels with names and titles are often hidden in nooks. Figuring out what you are looking at sometimes requires lengthy gallery crossings, which perhaps opens the work to interpretation but also renders concrete fact rather difficult to obtain. All the same, the strongest parts of the Bourse are the lightest: the animatronic mouse that comes out of the wall by the elevators, quiet enough to be ignored by visitors; the Maurizio Cattelan pigeons that hover right below the roof, as if they had snuck through broken glass. Throughout the galleries are black chairs covered with pillows or books. They are part of The Guardians, a work by the Paris-based artist Tatiana Trouvé that comments on the invisible presence of museum guards. An impish move, to fill a museum with chairs one cannot sit in. But I wasn’t sure if you were meant to laugh.

For more information on the Bourse de Commerce, visit the Pinault Collection website.

From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.