In late 1972, Bruce Nauman’s first museum survey opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The 31-year-old artist had graduated from the University of California, Davis just six years before yet had already earned himself a reputation as an experimentalist with an almost pathological aversion to being pinned down – zipping from sculpture and drawing to photography and video. Yet not everyone was convinced of his worth. ‘There is pathetically little here that meets the eye,’ Hilton Kramer wrote in the New York Times when the show travelled to the Whitney in New York in 1973. ‘It is pretty cold stuff, and pretty boring […] As an aesthetic enterprise, Mr. Nauman’s work bears about the same relation to visual art as crossword puzzles bear to literature.’

Untitled (Heads) (2005), Bruce Nauman. Photo: Jason Mandella. © 2018 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I heard Kramer’s words ringing in my ears as I slogged through the final rooms of MoMA’s gargantuan survey of Nauman’s career. One thing is for sure: few would describe him as ‘boring’ these days. His early performance videos – in which he makes extraordinarily repetitive motions, sometimes for periods of up to an hour – could hardly be described as ‘entertaining’; the artist himself is apparently bemused at the idea that anybody would bother to watch one from start to finish. Yet this meticulous, exhaustive and, it must be said, exhausting retrospective (which takes up not only a floor of the museum on 53rd Street, but also the entirety of its PS1 outpost in Queens) underlines the fact that Nauman is one of the most inventive and imaginative cultural figures of the past half century, an artist who not only changed our idea of what art could be, but did so again and again and again. Even Robert Hughes – another critic with an allergy to Nauman’s work – grudgingly described him as ‘the most influential American artist of his generation’.

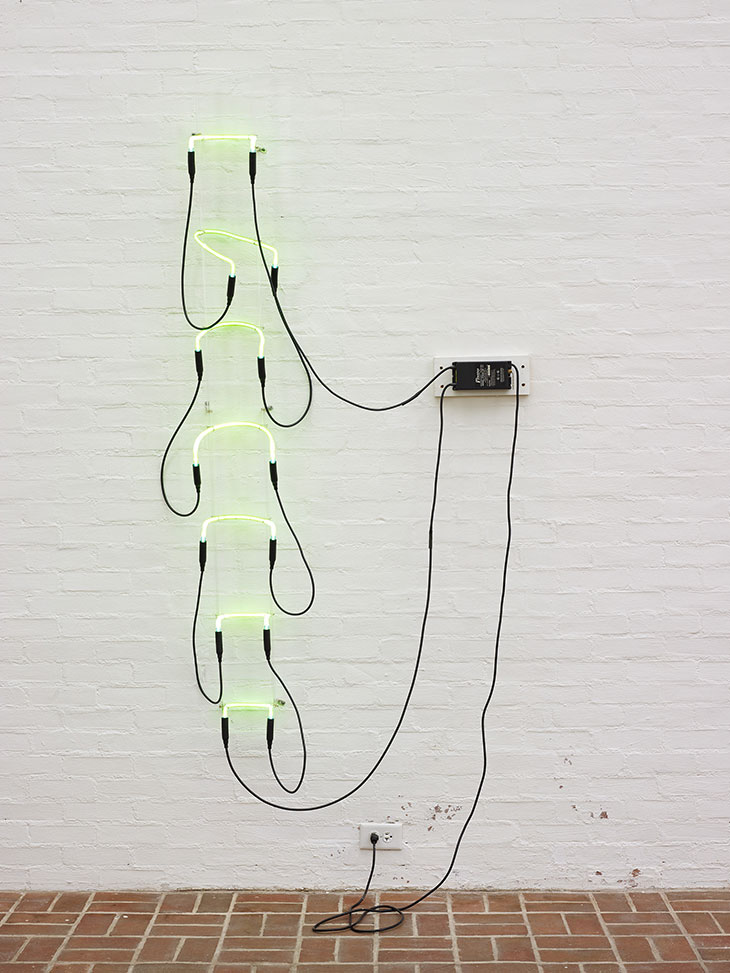

Nauman has turned his hand to forms including sculpture, performance, video, speculative architecture, installation and hard-edged conceptualism and is also, as we learn through a wonderful selection of plans on view throughout the exhibition, a supremely gifted draughtsman. But all this was secondary to the core principle of his Duchampian modus operandi: the idea that anything he did in his studio – including, in one project from the 1980s, a multichannel video of the (empty) studio itself – could be art if he deemed it thus. It’s remarkable how effortlessly he appears to pick up an idea and explore it before moving on to the next one. The early years are particularly illuminating: one moment, he is exploring the limitations of language with neon text pieces; the next he is casting the void under his chair and thereby giving material expression to the concept of ‘negative space’ taken up by Rachel Whiteread in the 1990s. In Going Around the Corner Piece (1970), another prescient work featuring a huge, white structure equipped with its own CCTV system, he anticipates the rise of surveillance culture and by extension, the wave of contemporary art that has responded to it. The visitor rounds the corner of the building only to see themselves vanishing out of shot on a television monitor.

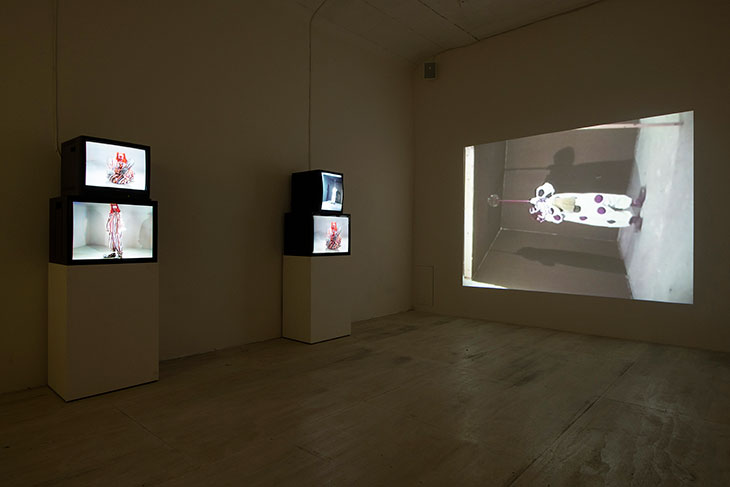

Installation view of Clown Torture (1987) in ‘Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts’ at MoMA PS1, New York, 2018. Photo: Martin Seck. © 2018 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art, New York

You can pick out the odd recurring theme in this survey. Throughout his career, Nauman has returned to the kind of performance art in which the performer suffers. The video installation Clown Torture (1987), one of his few truly emblematic works, gives us a costumed and face-painted figure being forced to repeat a series of phrases and actions to the point when physical pain sets in. Sometimes, we’re the ones made to suffer: Learned Helplessness in Rats (Rock and Roll Drummer) (1988), an installation featuring concurrently playing videos of a rat in a plexiglass maze and an amateur rock drummer joylessly hammering out a beat, is something of an endurance test. The crazed, repetitious drumming echoes through PS1’s galleries, inducing a pronounced sensation of anxiety. The joke, if it can be described as such, is that Nauman lifted the work’s title from a scientific paper entitled ‘Stressed Out: Learned Helplessness in Rats Sheds Light on Human Depression’.

Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body Taken at Ten-Inch Intervals (1966), Bruce Nauman. Philip Johnson Glass House Collection, National Trust for Historic Preservation. Photo: Andy Romer Photography. © 2018 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I had spent a full eight hours beholden to Nauman’s vision by the time I reached Learned Helplessness in Rats and I was starting to identify with the hapless rat as it scurried through the passages of its prison, like a test subject under some bizarre form of clinical examination. Throughout this trial, Nauman himself remains elusive, despite the fact that much of his output is built on his physical presence – he appears in videos, casts parts of his own body, at one point provides a comprehensive breakdown of his vital statistics. Yet, uniting his varied bodies of work is a chilly sense of impersonality, in which the artist surrenders as much autonomy as possible to whatever technology he has to hand, privileging accident over design. To return to Kramer’s words, it is ‘pretty cold stuff’ indeed. In so many ways, this is an awe-inspiring feat of exhibition-making, with more than 150 artworks reminding us of Nauman’s groundbreaking genius – but it’s utterly draining, too.

‘Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts’ is at MoMA until 18 Febuary and at MoMA PS1 until 25 February.