On 2 February, the CIMA (Centre of International Modern Art) awards ceremony in central Kolkata kicked off with Indian star musicians Bickram Ghosh and Ghatam Suresh beating out hectic rhythms on tabla drums and clay pots. During the ceremony, Nicholas Coleridge (chair of the V&A’s board of trustees) spoke about the importance of creative thinking and Deborah Swallow (director of the Courtauld Institute) received awards – both have long relationships with India. The state of Bihar was also honoured for its brave choice of the Pritzker Prize-winner Fumihiko Maki to design the government-funded Bihar Museum in the capital, Patna.

The night accurately reflected the unusual spirit of Kolkata – a complex city that continues to thrive on its historic bedrock of intellectual enquiry and political engagement – as well as the innovative template of the awards themselves. With seven artists on a nine-person jury panel, they aim to help young Indian artists gain visibility. Rakhi Sarkar, who opened CIMA in 1993, initiated the awards in 2015. This year is the third edition. She sees them as ‘a celebration of creativity, excellence and freedom of thought. It’s a way to unleash young talent, to remind us of eternal values. Our aim is to create a level playing field for all, including artists living far away from the cultural elite of cities.’ Competitors must be artists from India and under 45 years old. That’s about all in terms of requirements. Entry is free, and the first round of submissions are received online – India’s public Wi-Fi stretches solidly from the Himalayas to the fishing villages of Tamil Nadu; the vast majority of 1.3 billion citizens are connected. The identity of entrants is kept anonymous until the awards have been decided. At that time, this year’s entrants were found to have come from 21 out of India’s 29 states. Sarkar’s only disappointment was that just 20 per cent were women; ‘It’s essential we bring them to the forefront,’ she says.

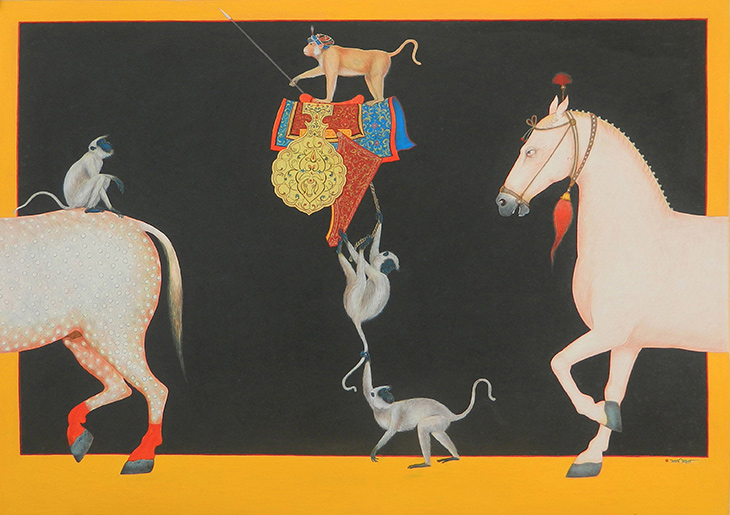

Dance of Democracy (2017), Partha Mondal

The CIMA Awards Show, curated by Rakhi Sarkar and her sister Pratiti Basu Sarkar, filled three venues: the centre’s string of white-walled galleries, the historic Gem Cinema, and the alternative art space Studio 21. In a country whose cultures vary widely and have art traditions going back more than 3,000 years, and whose people inhabit a lively democracy today, the 170 or so selected works varied hugely in inspiration and frequently contained social comment.

At CIMA, Partha Mondal’s small tempera painting on paper Dance of Democracy (2017) gives a political twist to the traditionally philosophical court paintings of north India, while Anil Nana Chouhan’s large watercolour Lost in Urbanisation (2017) draws on the dreamy landscapes of Rajasthan’s Mewar painting school to criticise the loss of India’s forests and the loneliness and pollution of urban life. More optimistically, Mahua Sikdar looks to India’s rich textile tradition for her untitled textile work made using the kantha and chikan stitches of eastern India. Global topics are also addressed, as in Navya Nataraja’s Buzzing Bees (2018), a hand-woven sculpture using copper wire, metal and glass beads. In contrast, Mumbai artist Rajesh Prakash Wankhade’s oil-on-canvas painting Imbalance (2018) takes its cues from the Western-influenced modernism of the Progressive Artists’ Group of Bombay, founded in 1947, which included M.F. Hussain and F.N. Souza.

Imbalance (2018), Rajesh Prakash Wankhade

The celebration spread out from CIMA to the rest of the city. The 10-day Kolkata Arts Festival staged one-off performances, free and open to all, at some of the city’s landmarks – the legendary dancer Tanusree Shankar performed with her troupe at the Victoria Memorial beneath the statue of Lord Cornwallis; superstar playback singer Usha Uthup sang on a sunset cruise down the Hooghly River. The Chitpur Craft Collective created an art trail through the lanes, art studios and historic buildings of their neighbourhood.

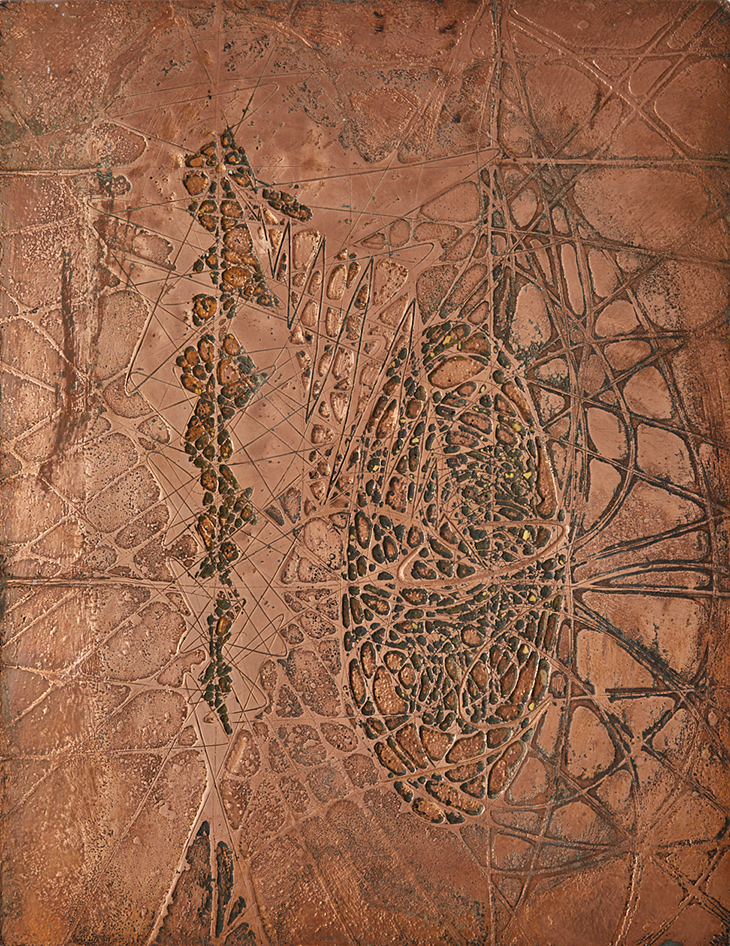

Elsewhere, Experimenter Gallery – one of India’s most respected champions of contemporary art – took a reflective moment with an exhibition dedicated to Krishna Reddy (until 31 March). Reddy trained at Santiniketan in rural West Bengal under Nandalal Bose, moved to London where he attended Henry Moore’s sculpture classes at the Slade, then joined Stanley William Hayter’s print studio Atelier 17 in Paris. There, he worked alongside visiting artists including Miró, Brancusi, Picasso and Giacometti while inventing simultaneous multicolour viscosity printing, a new form of intaglio printing. He later went to the US where he further developed his techniques; he died in New York last year aged 93. The show, ‘To a New Form’, exhibits for the first time some of Reddy’s early drawings exploring human and organic forms, and some of his multicolour prints together with their deeply engraved etching plates. Delhi collector Kiran Nadar has bought the entire show for her museum.

Two Forms in One (1954), Krishna Reddy. Courtesy the Estate of Krishna Reddy, and Experimenter