From the January 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

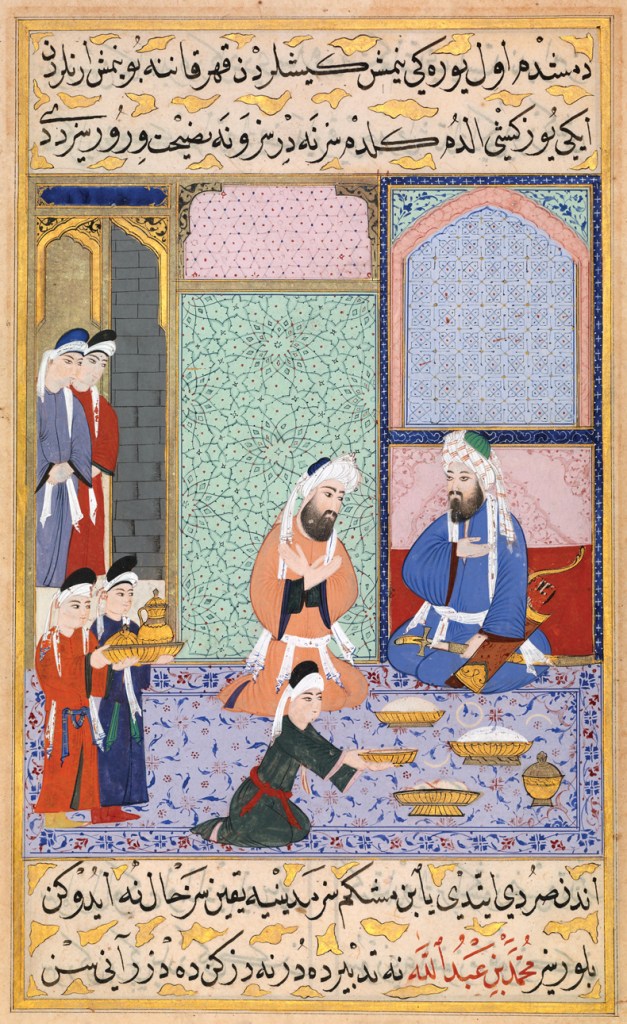

There are many manuscripts from the Mughal and Ottoman traditions with beautiful illustrations depicting people in domestic or military settings. A new exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, ‘Dining with the Sultan: The Fine Art of Feasting’, presents many exquisite folios that show scenes of feasting (until 4 August). A 16th-century Turkish watercolour from the Siyar-i Nabi (‘Life of the Prophet’) is a particularly fine testament to the hospitality of Muslims all around the world.

When it comes to my personal experience of such feasts, I still remember my first trip to Morocco some 50 years ago when a friend in Marrakesh invited me out for a meal. I didn’t know much about Moroccan food and expected a simple meal like one I would have in a London restaurant. Instead, I was treated to a proper diffa. The word means ‘reception’ in Arabic and is typically used for a lavish meal where practically the whole range of the Moroccan culinary repertoire is on offer. Charles Perry, the foremost expert on medieval Arab cookery, explains the word differently: ‘Despite the unexpected vowel i, rather than a, in the first syllable, it appears to be the literary word “daffa”, meaning a crowd or jam of people, specifically a throng crowding to get food or water. That has a slangy feel, so I suspect that it came into use as the word for a banquet in post-medieval times,’ he writes. Diffas are normally reserved for special occasions, both religious and secular, but they are also laid to honour special guests, especially those from abroad.

We started with pastilla, a dazzling sweetsavoury pigeon pie dusted with powdered sugar and cinnamon. It is made in three separate layers: ground toasted almonds mixed with sugar, eggs scrambled in the sauce in which the pigeons are cooked and tiny whole pigeons strategically placed under the top layer of pastry (nowadays everything is mixed and the pigeons are often replaced with boneless chicken). My host showed me how to eat with my hand, first by breaking through one edge of the crisp pastry to pull out a piece of the tiny bird and suck the meat off the bone before returning to pinch off more pastry with a little of the egg and almond fillings. Already on the table were dainty plates filled with delectable salads, cleverly placed near the guests, so that they can dip into them to refresh their palate between courses.

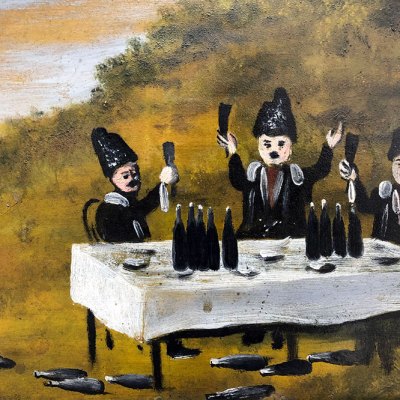

A scene of feasting from Sultan Murad III’s Siyar-i Nabi or ‘Life of the Prophet’ (c. 1594). Museum

of Fine Arts, Houston

The second course was mechoui (meaning ‘roast’ and used either for a whole lamb or in our case, a beautiful crisp, golden shoulder with some of the ribs still attached). Then came a couple of tagines. First a savoury chicken with preserved lemons and olives, then a sweet-savoury lamb with prunes finished with honey and orange blossom water and garnished with toasted almonds. The final course was a seven-vegetable couscous – to make sure no one was left hungry, my host explained. Dessert consisted of a selection of almond-filled pastries including cornes de gazelle, seasonal fruit and a very sweet mint tea that was ingeniously poured from high up into exquisitely decorated mini glass tumblers.

It was not until some 12 years ago, long after I started writing about food and I was co-presenting a TV series in the United Arab Emirates called Al Chef Yaktachef (‘The Chef Discovers’) that I started my pursuit of one of the most prized Islamic feasts. My copresenter was a poet called Tarek al-Mehyass whose role was to introduce me to traditional Emirati dishes which I would then adapt for modern times. One of the episodes centred around a camel feast that our host had planned to welcome his brother’s return from a long business trip – I was once told by a camel butcher in Aleppo that Muslims favoured camel meat because it is said to be the only faithful species in the animal kingdom; apart from this, centring feasts on whole camels is still the ultimate luxury, despite modern life and oil wealth encroaching on Bedouin lifestyles. When heads of state visit, royal cooks arrange whole baby camels in a seated position and lower them into huge pit ovens to roast before carefully lifting them to place them, still in the same position, on to huge platters already piled high with fluffy rice and bring the platters into the banqueting hall. However, my excitement at having my first taste of camel hump (considered to be the choice cut, mainly because under the fatty hump two tender filets are nestled between the ribs and back bone) died when I was shown to the women’s quarter.

This injustice set me off on a hunt for my very own camel hump. It took two years before I was finally able to realise my wish when a friend in Sharjah gave me a whole baby camel after hearing my sorry story. I limited myself to the hump, which I carried back to my brother’s kitchen in Dubai. There, I marinated it in rose water, saffron and a spice mix called b’zar before roasting it until crisp and golden all over. I served it with a fluffy saffron rice for our own camel feast in miniature; and, in keeping with the tradition of eating with our hands, we pulled at the tender filets beneath the fat with our fingers.

From the January 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.