From the July/August 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

According to the Cameroonian scholar Jean-Paul Notué, the late 19th century was a golden age for the kingdom of Bandjoun, in the Bamileke region of the Cameroon Grassfields – the mountainous region in the west and north-west of the country. There was huge population growth, economic expansion and territorial enlargement – all of which contributed to a great cultural efflorescence. In the earlier part of the 19th century, Fo (or Fon) Kamga I was an important patron of the arts, who began to grow and organise the royal treasury – it was under his reign that the tradition of wooden sculpture adorned with beads began to develop. But the golden age really began with his successor, Fo Fotso I, who reigned until the 1890s. Fotso took the title of Foteh Tengsum – ‘the king for whom territory has no limits’. He was one of the kingdom’s great conqueror-leaders – as was his son, Fotso II, at least until the arrival of the Germans in 1905.

We know that this kuo (prestige stool) now in Cleveland was definitely made no later than 1925, when it was photographed by the French Protestant missionary Frank Christol, alongside Fo Kamga II. But in this photograph, it’s clear that repairs have been made to the seat of the stool; looking at the style of the object and the materials used, I believe that it was most likely made during the second half of the 19th century, and, if so, would have been used by Fotso I or II.

Prestige stool (possibly 1800s), Bamileke makers. Cleveland Museum of Art

Kuo stools are essentially travel seats. That said, this stool is extremely heavy – it’s certainly not ultra-lightweight camping equipment. But then, the king wouldn’t have been expected to carry it around himself – and when you compare it to the stools that would have remained in the palace, often adorned with human-sized figures, it’s relatively petite and portable. As such, it would have been a kind of all-purpose ceremonial object, used for functions when the king left the palace, or in more intimate settings within the palace itself.

The leopard is the symbol par excellence of rulers in Bamileke and other cultures throughout the Cameroon Grassfields. It was believed that animals could function as spiritual doubles, symbolising a person and their characteristics. With strength, power, speed and cunning, the leopard was seen as an animal that could master its environment. For the king to be sitting on a leopard was the ultimate sign of his power. In the Grassfields, art was above all an expression of power, with artists working for the Fo very much in service to his prestige. Artists – always male – were highly trained and specialised in their craft, whether it was carving, beadwork, pottery or metalwork, with skills passed down through long lineages. There were some independent studios but, more commonly, art was produced in royal workshops. Certain rules – dictated by religious, political or symbolic meanings – governed artistic styles. But from the time of Fotso I, the court and its entourage were commissioning art at such a prodigious rate that artists began to have greater freedom for innovation and originality, even though they were fulfilling commissions to please their patron.

The stool certainly speaks to the individuality of its maker – or makers – in a variety of ways. The leopard possesses real vitality and tension, with its distinctive pose of feline alertness: legs tensed, eyes wide, ears pricked forward and alert. It’s clearly a cat who’s ready to pounce. We don’t know who made it – whether it was a carver collaborating with a bead artist, or a single artist trained in both specialisms. But the form is less elongated than many sculptures we know to have been created in the Bandjoun kingdom – the body is rounder, the limbs more tubular, the paws non-delineated. There’s also one remarkable detail: the raised tail of the leopard supports the seat of the stool, which is possibly unique to this object.

While it’s difficult to define a ‘Bandjoun style’ as such, these are little hints that this artist may have trained elsewhere, or looked to the styles of other kingdoms nearby. This speaks to the great blending of styles throughout the region at this time. Well-known artists were commissioned from afar, or sometimes took up residence in courts. Artworks were also given as diplomatic gifts or as tributes, or sometimes taken during disputes or wars. There are many ways this stool could have come to the kingdom of Bandjoun.

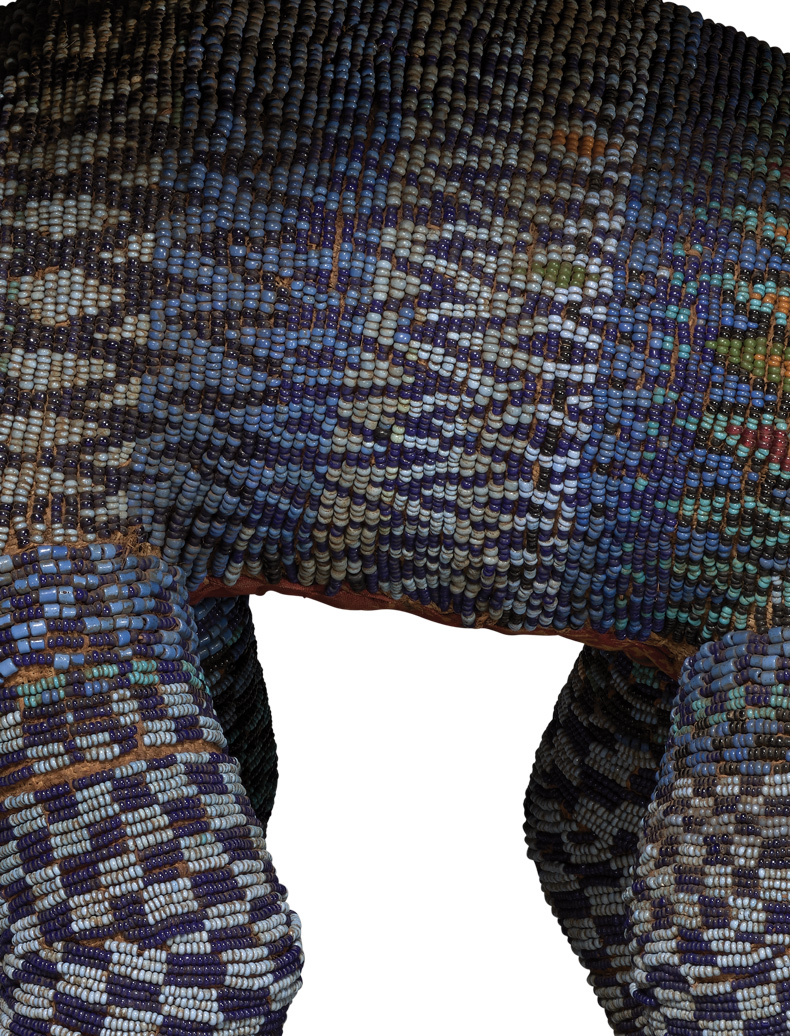

Changes in the patterning in the glass beadwork emphasise the form of the leopard

The artist’s delineation of volume with the beadwork patterns is extraordinary. We have not yet scanned it to understand how fully carved it is beneath – for example, to see how well realised the facial features are. But what is apparent is the huge variety of ways in which the artist uses the beadwork to emphasise the form. Where the joints of the limbs attach to the body, for instance, you see changes in colour, direction and patterning of the beading. There’s an expert knowledge both of design sense and material technique – for instance, in the skill required to minimise the rows of beads in order to have them turn the curve of, say, the inner arm joints. As for the patterns themselves, this is classic Bamileke geometric symbolism. You can think of both the checkerboards and the zigzag-and-diamond motif as distilled elements, each symbolising the power of the leopard.

Beadwork is a very prestigious art form, still practised across the Grassfields. Its origins aren’t entirely clear; in Igbo-Olokun in present-day Nigeria, there is evidence of glass beadmaking taking place between the 12th and 16th centuries, but it wasn’t particularly widespread. Before the importation of glass beads, various cultures across Africa used beads made of natural materials – snake vertebrae, shells, stones, seeds and, especially, coral. The Benin kingdom is also noted for its stunning ensembles of coral beads. And in the earlier moments of the cultures that are today the Grassfields kingdoms, coral beads in red and blue were particularly prized.

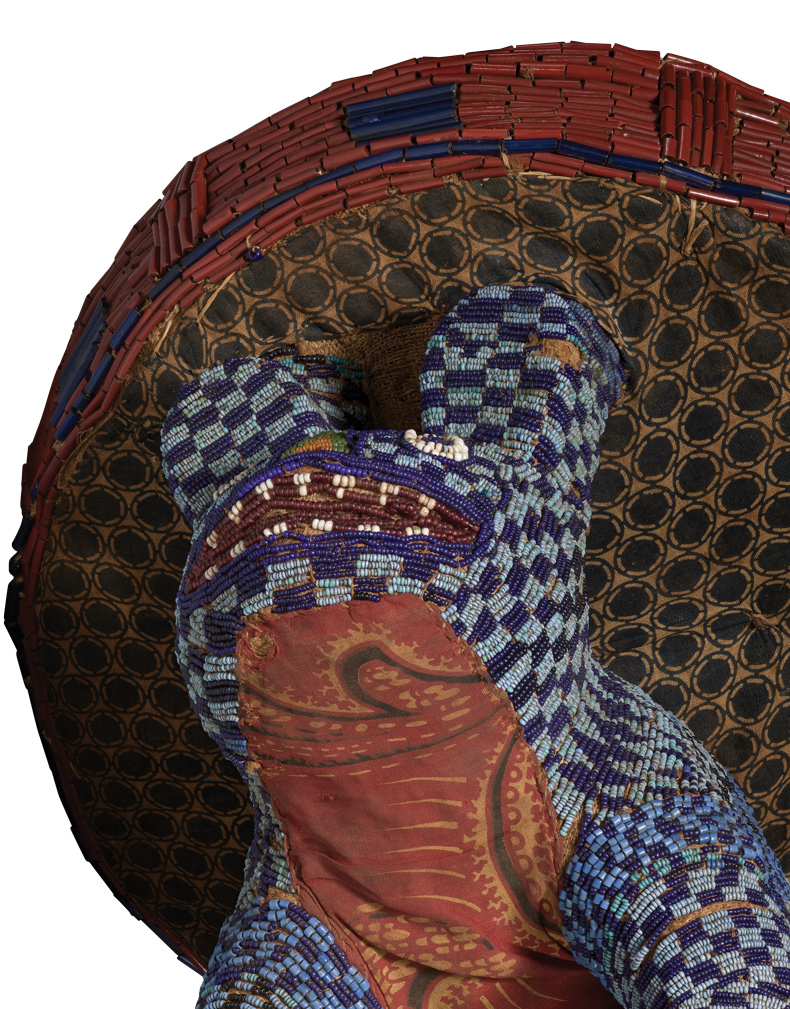

The story is often told – and there is some truth to it – that it was with the arrival of Europeans, bringing beads from Bohemia, Venice or India, that beadwork really took off. But there’s a common misapprehension about the way these beads were traded, with the assumption being that Europeans would show up with boxes of beads and dump them at the port, departing with whatever they needed in exchange, with Africans just taking the beads and innovating. In fact, there was a great deal of African agency in the ways that European beads came into the supply chain. Cameroonians in the Grassfields would acquire them from middlemen on the coast of Cameroon or present-day Nigeria, trading them for animal pelts, salts or enslaved individuals. So the beads arrived in the 19th century as part of a network of prestige materials – one which was highly selective. There are accounts of Europeans arriving with beads, only to be flummoxed when African populations refused to take them – they preferred the ones they had already. In the case of the stool in Cleveland, the tubular beads of red and blue on the seat and the socle are imitations, created by Europeans to mimic the coral beads that were so prestigious in the Grassfields.

The Turkey red printed fabric on the belly of the leopard was imported from abroad

On the underside of the seat, and the underbelly of the leopard, the artist has also incorporated textiles. Again, these cloths are imports – and again, they speak to African agency in material trade. There were local markets, local tastes – and there were many disappointed European textile merchants who arrived on the west coast of Africa only to find that their wares had gone out of fashion. Here, the blue-and-white printed fabric on the underside of the seat meshes beautifully with the geometry of the beadwork. The fabric on the belly of the leopard is of a type called ‘Turkey red’ – created by Indian or Turkish artists and brought to Europe in the 1740s. In a story similar to that of the more famous Dutch wax prints, which were based on Indonesian batik, English and Scottish factories became major producers and exporters of this style – with its distinctive palette of red and yellow – adapting it to the tastes of African consumers such that, as here, you have Turkey red fabric with a Paisley-type pattern. While there were Turkey red textiles with figurative or animal motifs, I have yet to see an African artwork incorporate them, suggesting that they were not imported, because African consumers didn’t like them. The fabric has been sewn beautifully, with as much care as has gone into the beadwork. The king wasn’t just sitting on a symbol of power in the form of the leopard – the stool was also a symbol of his access to foreign goods, his international might and reach.

I’ve been researching this stool closely for several years – and like every African work in Western collections, the stool has a unique provenance. I compare curators conducting provenance research to scientists doing experiments. We make hypotheses based on the best information that’s available to us and then we refine these ideas as new information comes to light. When we acquired this work in 2006, it was hypothesised through documentary evidence and the assessments of scholars on Cameroon that it had left the country in around 1925 with the missionary Frank Christol. We thought that it was perhaps a gift from Fo Kamga II, or one of a number of objects that Christol sold to the French dealer Charles Ratton. But as a result of more research tools and resources being at our disposal nearly 20 years on, we have realised that the provenance is actually more enigmatic. I’m researching the archives of Charles Ratton, as well as the recently digitised photographic archives of Frank Christol in the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. Given the ways in which, in recent years, oral histories have transformed our understanding of pieces in the Musée de Bandjoun, I wouldn’t rule out the possibility of a trip to Cameroon to speak with contemporary bead artists to elucidate the history of this fascinating object further.

As told to Samuel Reilly.

Kristen Windmuller-Luna is curator of African arts at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

From the July/August 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.