On both sides of the Atlantic, commercial galleries are opening new locations in small towns or holiday destinations, at a considerable distance from established art market centres. Could decentralisation be a way for mid-tier galleries to thrive and expand in a sustainable, artistically generous manner? And might it be a workable solution for galleries who no longer wish to operate in London or New York at all?

Plenty has been written in recent months about the economic challenges facing mid-tier, single-city commercial galleries, and the pressures exerted by rising rents, expensive business rates, the need to participate in the annual art-fair circuit, and the relentlessness of a swiftly rotating exhibition schedule. In the UK, there is a rising murmur among artists, curators, writers, and some commercial gallerists that living and working in London is becoming untenable. If there are increasingly urgent calls for the model to be reconfigured (or even reinvented), few viable alternatives have been imagined. Nevertheless, a growing number of commercial galleries, with established profiles and rosters, are undertaking ventures which five years ago would have seemed out of kilter with the consolidation of the art trade in St James’s, Mayfair, Soho, and Fitzrovia.

These intriguing developments include respected dealers launching outposts in seaside towns. In Hove, Maureen Paley’s Morena di Luna opened last July with a solo show by Paulo Nimer Pjota, and the gallery’s 2018 season will start with an exhibition by Kaye Donachie. Next year Carl Freedman, who runs both his eponymous gallery and Counter Editions, an online print-specialist selling fine art editions and multiples, will open a gallery space and residency in the Thanet Press building in Margate. This commercial building from the 1960s had been slated for demolition prior to its acquisition in 2016 by fellow dealer Jonathan Viner – whose vision for a ‘creative hub’ on the site, which will include his own gallery, is a natural evolution of the town’s Turner Contemporary-led regeneration. Further afield, Thomas Dane will open a new location in Naples in early 2018, part gallery, part residency: ‘a different space and experience for the artists’, he says, with ‘less pressure and fewer distractions’.

What these moves share – beyond their sense of adventure – is the decision to expand not to New York, the beating heart of the contemporary market, but to economically and socially deprived destinations well beyond established art-market centres. All are also artistically driven, with a shared motivation to be generous to artists, giving them time to breathe and space to experiment. One inspiration, perhaps, is the successful expansion of Hauser & Wirth to Bruton, Somerset, where the gallery has received nearly half a million visitors since it opened in 2014. This outpost demonstrates the possibilities of lateral thinking, combining a well-conceived programme with accommodation, educational provisions, artist residencies, a restaurant, functioning farm and landscaped gardens designed by Piet Oudolf.

Of course, for what is one of the most successful international galleries in a generation, this expansion to rural England is unlikely to be justified as simply an economically driven enterprise. Perhaps it might be better explained through the personal connection of Iwan and Manuela Wirth to Bruton, as a retreat from the city where they have lived since 2010. Indeed, a privately felt connection to a host town or city has been instrumental in driving decisions to open gallery outposts: Dane credits artist and designer Allegra Hicks as the catalyst for opening in Naples, saying that she has introduced him to almost every- one who has made the development possible; Viner first acquired property in Margate in 2011 and sees it having huge potential as an art destination; and Freedman has been visiting the town for more than two decades. Similarly, Maureen Paley opened Morena di Luna after owning a place in the city for 14 years, often bringing friends and artists to explore Brighton and Hove.

Last August, the David Roberts Art Foundation announced that it was closing its permanent home in London – citing, among other things, the comparatively small number of visitors in the capital – and would reopen as a sculpture park in Charlton Musgrove, Somerset, in 2019. Declining visitor numbers in the East End of London are one consideration behind Freedman’s decision to open in Margate; he observes that five years ago the East End was an important destination for art lovers, collectors, and museum groups, with regular footfall, but that art fairs and the blue-chip occupation of Mayfair have lessened the pull of East London. Freedman expects that many visitors would rather make a pilgrimage to Margate than regularly trawl through shows in London. Also responsible for declining face-to-face interaction with clients is the growing comfort of buyers making transactions remotely via digital images and at fairs; Freedman remarks that more than 50 per cent of the gallery’s business is done outside its physical premises.

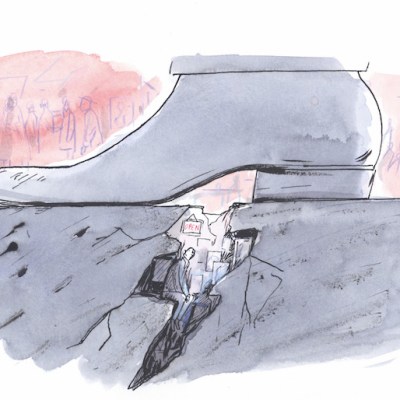

Another common factor motivating the decision to open outside London is the possibility of a slower, more considered rhythm to exhibitions – with longer runs, and space to make art and produce exhibitions with less background noise. Dane comments that his gallery’s expansion will mean more time ‘to look and think’, with the space in Naples running ‘fewer, longer shows, three shows a year […] The programme between London and Naples will have a symbiotic relationship, maybe with shows travelling in both directions’. Meanwhile Viner, whose premises in Margate will be his only space, is expressly invested in changing the conventional gallery exhibition model with shows running from three months to a year. A trip to Marfa, Texas, where he saw what Donald Judd had achieved with old buildings as places to produce and present art, has inspired him; in Margate and the Thanet Press building, Viner senses that he has found something special, with ‘both the scale and building type being perfect […] working at a new scale and in new architecture beyond the white cube are very exciting’.

By opening a location with a much lower price per square foot, galleries are able to facilitate and enable production in ways that would be economically unviable in London. Artist’s residencies are common to the initiatives of both Freedman and Viner in Margate, and Dane in Naples, envisaged as open-ended programmes in which artists will make work in the local context. For Freedman, who curated several of the early YBA exhibitions in London (including ‘Gambler’ in 1990), setting up shop in a warehouse in Margate will entail a return to the creative possibilities of large, empty spaces – vital for creative energy and freedom, he believes, but currently hard to come by in London. Even though London will never be replaced as the UK’s art market centre, it is no longer a hospitable place for the creative spirit.

Joel Mesler, an American dealer who has run galleries in Los Angeles and New York, recently closed his Lower East Side space to open a mom’n’pop scale business in East Hampton, catering to the wealthy collectors who flock there during the peak season of the summer months. In an interview with the Financial Times, he remarked that by losing excessive New York overheads, and operating with more of a project space model that abandons the idea of artist representation and exclusivity, he has ‘gained time to reachieve joy in the gallery system’. For all that UK gallerists are opening outside London for a variety of reasons, Mesler’s words perfectly encapsulate the sentiment that permeates their new ventures.

From the January 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.