Although Caspar David Friedrich is today thought of as a painter of oil on canvas, he returned continually throughout his life to paper and ink, making sepia-toned works of precise penwork that treat delicately his great subject, the natural landscape of his native Germany. The exhibition ‘Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature’, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is bookended by these works on paper as part of a comprehensive survey of his career. This curatorial choice underscores an unexpected revelation: the essential minimalism in Friedrich that is often overwhelmed by the soaring pines, snowy cemeteries and gleaming crosses that have earned him a reputation as a heavy-handed, sentimental maximalist. But in Eastern Coast of Rügen with Shepherd (1805–06), a quiet expanse of monochromatic ink-wash sky and field is balanced exquisitely by an intimate moment in the foreground between a shepherd and his dog. The Mist in the Mountains (1807–08) in oil captures the mightiness of a mountain peak by obscuring it almost entirely with swathes of grey-white mist. Romanticism’s typical demand that we confront something vast and eternal is made here by a canvas overwhelmed not by solid stone but by diaphanous air.

The use of vacancy on a grand scale is especially powerful in The Monk by the Sea (1808–10), in which a robed figure stands on a frosty and desolate heath against what must be an unbearable chill coming off the open sea, an expanse of delicate white caps on choppy water swallowed up at the horizon by an ombre sky from light grey to dark. The exhibition includes just next to the canvas a reproduction of the underpainting, revealing that Friedrich planned to put ships on the water in an earlier composition. The exclusion of those ships is as bracing as the exclusion of people in certain of his landscapes. Where other Romantic painters might have inserted human action or presence to tell us what or how to feel about our finitude, especially in comparison to nature – such as hikers beneath the grandeur of a mountain peak or ships up against the force of the open ocean – Friedrich instead omits markers of human activity, leaving us with nothing but an abyss. It is moving, existential and, perhaps, even radical.

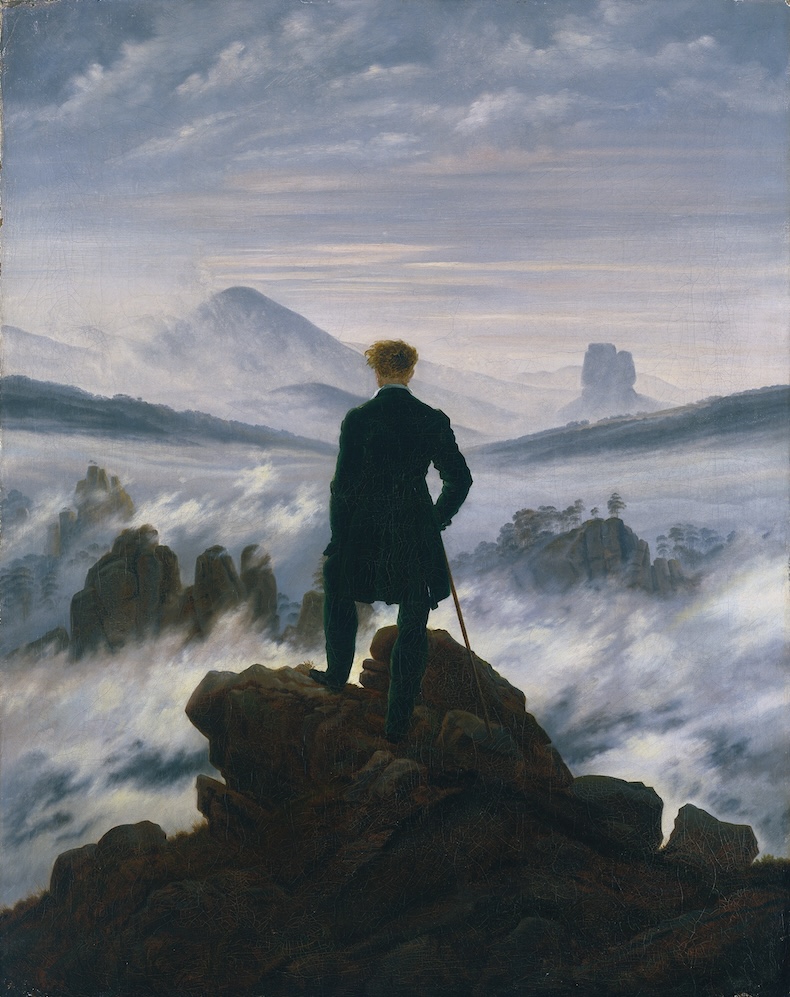

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c. 1817), Caspar David Friedrich. Hamburger Kunsthalle (on permanent loan from the Stiftung Hamburger Kunstsammlungen)

Landscape painting of the Romantic period is full of minuscule humans, placed in the scene to scale the grandeur of the nature around them. The desired effect is a sense of awe in the viewer at the sheer might of nature, that by perceiving such a contrast they might experience a simulacrum of the awe they might feel in the presence of a mountain. Another way of pulling the viewer into the work was by making the figure in a painting face away, towards a landscape or expansive ocean view, the true subject of the painting. The German term for this is Rückenfigur (literally ‘back figure’) and when it came to painting people, it was reliably Friedrich’s mode. Whether beholding the moon or trudging through the snow into a forest, his figures have turned their backs. The facelessness of the back-figure creates the same effect as the tiny adventurers; if the subjects are no one, they can be us.

Yet Friedrich also plays with that surrogacy. In Woman at the Window (1822), the whole effect of Rückenfigur is undermined. Instead of a landscape we are in a domestic interior, as the subject (modelled by Friedrich’s wife) leans lazily against a windowsill, looking out. We can glimpse through the window and over her head the mast of a small boat – perhaps gliding by on a canal below – but nothing more. Her interior world is no longer open to anyone, but instead that of an entirely closed-off individual, a stranger.

Griefswald in Moonlight (c. 1815–1817), Caspar David Friedrich. Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo

One might come to this show solely for the most recognisable of Friedrich’s paintings, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1817), a work for which we might thank the fact that Friedrich was reportedly bad at painting faces. But the lesser-known canvases reveal his mastery of other painterly techniques, in particular with regard to light. In The Ruins at Oybin (1812), a sunset sky breaks through the lancet windowpanes of a crumbling monastery in three firm columns of rich orange and yellow. Some of the most successful paintings on view are a series of small-scale mid-career studies of light, such as Griefswald in Moonlight (1815–17), Coastal Landscape in Morning Light (1817) and the stunning Evening (1824), which consists almost entirely of a cloudless sky, the few present clouds themselves the subject as setting sun ignites the demurring whisps of cirrus. In focusing on the play of the light and the landscape, these exercises let nature speak for itself – in a way Friedrich often doesn’t when forcing the issue with instructive back-figures. The friends poised arm-in-arm in Two Men Contemplating the Moon (1825–30), for instance, are more a distraction than anything. Likewise, Friedrich’s biggest failures in execution are when he relies on artifice, as in the stark sunbeams bursting across the sky like searchlights in Neubrandenburg on Fire (1834). The looming peak in The Watzmann (1824–25) is slightly cartoonish and unconvincing in its colouring – perhaps unsurprisingly so, since Friedrich never actually visited the mountain in question, but worked from studies by other artists.

In a portrait by his friend Georg Friedrich Kersting, Caspar David Friedrich in His Studio (1811), the painter sits at his easel in an austere workspace, light from the window controlled by shades, geometric measuring tools within reach, his hand steadied by a maulstick – there is nothing romantic here about the act of painting. The reputation of his work in his lifetime was divisive: he was funded by patrons, though Goethe is quoted as saying that ‘one ought to break Friedrich’s pictures over the edge of a table; such things must be prevented’. Kersting’s portrait seems determined to make the case for its subject as a serious artist. The gaudier elements of Friedrich’s style are today taken for granted, but the wall text next to Cross in the Forest (1812), in which a cross stands proudly underneath a glowing cruciform cloud, points out that this subject was a popular trend among elite patrons.

A Walk at Dusk (c. 1830–35), Caspar David Friedrich. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

By the end of his career, Friedrich had moved away from the natural world and towards a more social one, where his tendency towards literalism can get in the way. At the same time, there is the development of a more nuanced, psychologically cloudy tone, out of line with what we’ve come to expect. The exhibition leaves off with A Walk at Dusk (1830–35), in which a man hangs his head in contemplation while passing a funerary stone. Though he is faceless, rather than being the Romantic’s ‘any man’, the figure seems to be the ageing artist himself. The canvas is small and there is no mountain to move us but, even so, as when we were with the monk alone against the gaping maw of the dark horizon over the sea, there is a quiet, unwavering confrontation with a void.

Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until 11 May.