From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

She was a 365 party girl while Charli XCX was still in nappies, shared the boozy debris of her heartbroken bedscape decades before social media and talked openly about sexual assault and abortion when both were considered unmentionable. Even her insomnia selfies pre-empted the recent flush of menopause content. In many ways the world has caught up with Tracey Emin. These days sex, sickness and grief on the gallery walls barely raise an eyebrow.

Curiously, the most transgressive subject Emin addressed in a recent exhibition of paintings at Xavier Hufkens gallery in Brussels was not fucking, fellatio or even cancer. Monumental in scale, More Love Than you can Imagine (2023) presents the artist in repose, her face and upper body rendered in a flurry of dark lines suggesting she is lying on a bank of pillows. A smaller body sits alert before her, curled into the angle of her lap. A hovering cloud of sugar-pink paint identifies a zone of warmth and affection uniting the two. It is a romantic tableau. A public pronouncement. Two beings curled up in bed together. A woman and her cat.

The emotional connection between women and cats has become rich territory for mocking misogynists. In the months since I saw Emin’s painting, an interview from 2021 resurfaced in which Donald Trump’s current running mate J.D. Vance dismissed various Democrats (Kamala Harris among them) as ‘childless cat ladies’. Vance used the term to suggest that frustration with their own empty lives had inspired women ‘to make the rest of the country miserable, too’. ‘Childless cat lady’ here performs as code for a wayward older woman. As the political commentator Carole Cadwalladr has quipped: ‘They used to call us witches because we knew shit. We still do.’

This is a column about art, not politics, but there is shared territory here. An artist expressing their profound love for a cat is discomforting. Cats in Western art more often perform symbolic roles. A cat toys with a bird in William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience (1853), indicating the vulnerability of a woman treated as a plaything. The startled black kitten arching its back at the feet of Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) suggests animal pleasures of the night. As subjects in their own right, cats have historically been considered sentimental or humorous.

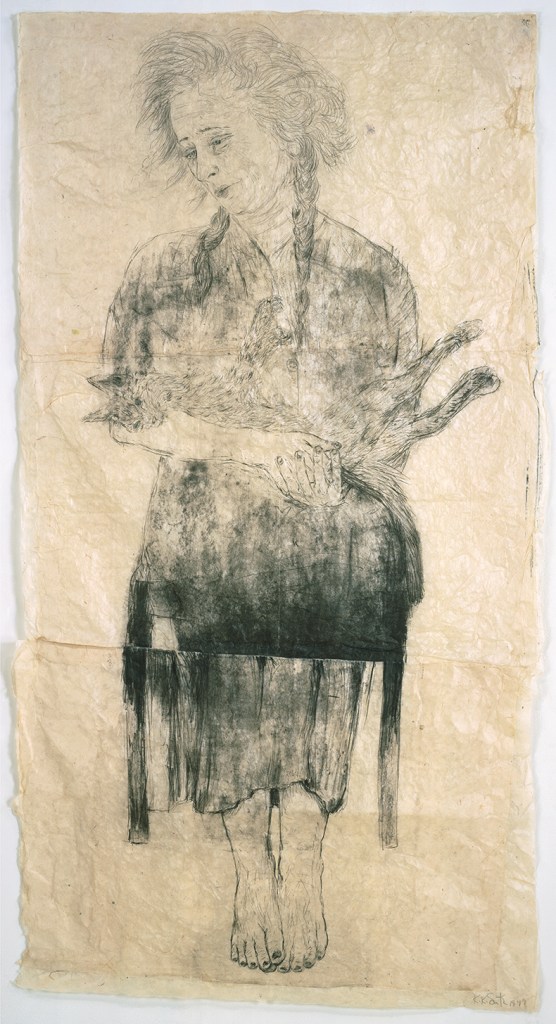

Pietà (1999), Kiki Smith. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo: G.R. Christmas; courtesy Pace Gallery; © the artist

Emin is not the first woman artist to honour the companionship and affection shared with a cat. An early work by Carolee Schneemann – Personae: JT and Three Kitch’s (1957) – shows the composer James Tenney lying naked, his swollen penis providing the painting with its focal point. This is thought to be the painting that inspired Schneemann’s expulsion from Bard College for ‘moral turpitude’. Look closely and you’ll see it is a painting of not one but four bodies: Tenney is accompanied by the cat Kitch who, true to contrary feline tendencies, appears in three different positions.

Kitch reappeared in the experimental film Fuses (1964–67), which is spliced from daubed and weathered Super 8 footage of Schneemann and Tenney’s daily life, including abundant documentation of sexual activity. Whether they are fucking in a window frame or embracing in bed, the cat is inevitably in the frame. Fuses was the first film in an autobiographical trilogy that concludes with Kitch’s Last Meal (1973–76), which again unfolds within Schneemann’s hybrid home/work environment. Here, a human relationship (with the artist Anthony McCall) plays a supporting role to the drama of Kitch’s advancing years. The elderly cat is presented with each meal as though it’s his last, and the film concludes with his death.

Schneemann enters stickier territory in the photo collage Infinity Kisses (1981–87), which documents a morning routine in which her cats wake her with a lick on the mouth. Admitting to similar intimacies with her dog in The Companion Species Manifesto (2003), the philosopher Donna Haraway reflects: ‘I’m sure our genomes are more alike than they should be. There must be some molecular record of our touch in the codes of living that will leave traces in the world, no matter that we are each reproductively silenced females, one by age, one by surgery.’

Like Kitch’s Last Meal, the drawings of Judy Chicago’s Kitty City (1999–2004) offer everyday scenes from a domestic life with cats: feeding, grooming, clearing out the litter tray. Chicago and her partner do their yoga routines or chat in bed while the cats jostle and rub for their attention. Self-portraits show Chicago metamorphosing into her cats: concluding images in a body of work the artist considers a ‘feline book of hours’.

While there is knowing humour in Schneemann and Chicago’s cat works, they should not be mistaken for jokes. Instead, they propose that we honour the overlooked in the day-to-day and give an honest account of our important relationships.

The final image in my book Acts of Creation is not of a biological mother, but a Pietà (1999) by Kiki Smith showing the artist holding the dead body of her cat Ginzer. Smith draws herself in a moment of deep grief, her hair wild, her eyes swollen, cheeks rubbed with tears. As with Emin’s More Love Than you can Imagine, this is a work about devotion – one that knowingly addresses an interspecies relationship that is overlooked, belittled and mocked. Each of these works proffers that most daring of invitations: that we take it seriously.

From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.