September is a month for estate sales and charity auctions – sometimes one and the same thing – and this year’s offerings come courtesy of celebrities of various kinds. The most cerebral, as one might expect, is the collection of predominantly abstract art formed by Edward Albee (1928–2016), arguably the foremost and most challenging American playwright of his generation – although one perhaps more admired in Europe than in his own country. Indeed, his first produced play – The Zoo Story – opened in 1959 in Berlin on a double bill with Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape. His unflinching explorations of the existential terror and capacity for human cruelty beneath the respectable veneer of American society more often than not played off-Broadway, but they still earned him several Pulitzer Prizes and Tonys.

With the royalties from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? – adapted into an Oscar-winning film with Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in 1966 – the playwright established the Edward F. Albee Foundation in Montauk, Long Island, as a residence ‘to serve writers and visual artists from all walks of life, by providing time and space in which to work without disturbance’. This foundation is the beneficiary of the 100 or so works of art offered by Sotheby’s New York on 26 September. Photographs of Albee at home in his bare-brick Tribeca loft show him surrounded by 20th-century paintings and sculpture, as well as African and Pre-Columbian sculptures. Some acquisitions were the result of relationships with artists, some related to devotional practices that interested him, and all seem to reveal his fascination with the processes of the creative mind. As he once said in an interview: ‘Art merely being decorative is insufficient – it is to hold up a mirror to ourselves.’

Meditation (1960), Milton Avery. Sotheby’s New York: estimate $2–$3m

A highlight of the $9m sale is Milton Avery’s Meditation (1960). In an essay on the artist, Albee wrote about rummaging through canvases in the Averys’ apartment: ‘I was young and poor at the time, and while Avery’s prices in those days were still a laugh, I could afford only one thing. I chose a canvas of two sprawled figures – one ghostly white, the other Avery blue, on a brown field – and went industriously back to my desk to write another play so that I could get some more.’ In Meditation, Avery has again distilled his subject to simplified forms and blocks of colour. ‘I am not seeking pure abstraction,’ the artist wrote in 1951, ‘rather the purity and essence of the idea.’ Estimate $2m–$3m.

On the same day in London, Sotheby’s offers Vivien: The Vivien Leigh Collection – works of art, jewels and memorabilia that have passed down through the family of this star of stage and screen described by Gladys Cooper as ‘the most beautiful woman of her age’. Christie’s London offers another tranche of Audrey Hepburn material in two parts – a live auction on 27 September and an online sale running from 19 September–3 October.

One of Angus McBean’s many photographs of Leigh was, coincidentally, the first photograph acquired by Mario Testino, one of the most celebrated fashion and portrait photographers of our age (his show at the National Portrait Gallery in London in 2002 attracted the largest attendance hitherto in its history). From 8–13 September, Testino takes over Sotheby’s London galleries to curate an exhibition to promote the 400 or so works from his own collection that are being sold to benefit MATE – Museo Mario Testino in Lima. Founded by Testino in 2012, MATE aims to bring Peruvian artists and culture to worldwide attention, as well as promoting contemporary art and photography to audiences in Lima.

Testino moved on from mid-century photography to collect the work of contemporary practitioners – such as Nan Goldin, Adam Fuss, Thomas Demand, and Wolfgang Tillmans. Through his close friendship with London gallerist Sadie Coles, he was introduced to fine artists who were using photography in new ways, such as Richard Prince, and that experience launched a passion for collecting contemporary art from around the world. He also collaborated on works with the likes of Keith Haring, Vik Muniz, John Currin and Julian Schnabel.

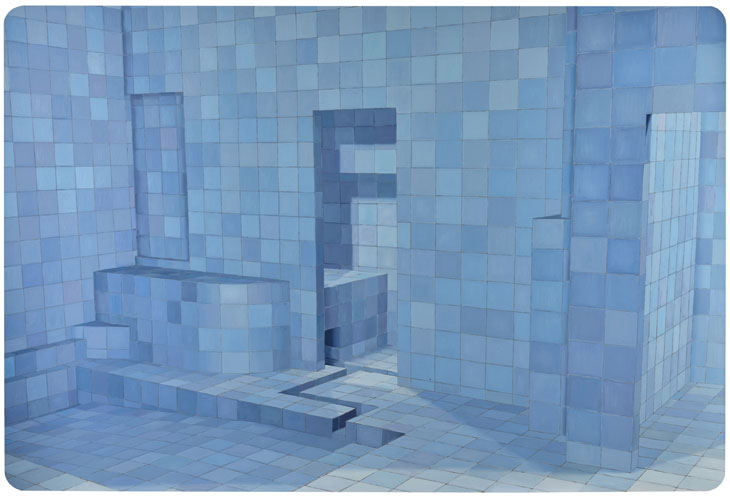

Blue Sauna (2003), Adriana Varejão. Sotheby’s London: estimate £400,000–£600,000

As one might expect, South American artists play a major role and one of the sale’s highlights is Brazilian artist Adriana Varejão’s Blue Sauna (2003). Tiles have long been a motif of Varejão’s work, most particularly the distinctive azulejo tilework of Brazil’s Portuguese colonial past. The large monochromatic paintings from her Sauna series, however, have a quite different mood and aesthetic; their eerie, empty, grid-like spaces, enlivened by subtle colour gradations, have an ambiguous atmosphere. There is a cinematic sense both of narrative suspended and of something about to happen. Estimate £400,000–£600,000. The two-day fine art auction on 13–14 September will be followed by an online sale of photographs.

Studio ceramics are the primary focus of this September’s Made in Britain sale at Sotheby’s London. Some 50 lots are included, from the menagerie of strange saltglaze stoneware birds and beasts created by the Martin Brothers in the late 19th century, to contemporary pieces by the likes of Gabriele Koch, Grayson Perry, Edmund de Waal and John Ward. There is also a strong group by the great Lucie Rie, a protégé of Josef Hoffmann in Vienna. Rie’s spare domestic vessels, often bearing brightly coloured or textured glazes, remained essentially modernist and urban in contrast to the prevailing rustic pottery of the day. She created surface interest by overlaying slips and glazes on to an unfired body, often adding metal oxides that bled into the glaze. Included is a glorious deep mustard-yellow footed bowl with a wrinkled bronze rim that belonged to her biographer, the potter Emmanuel Cooper (estimate £8,000–£12,000).

A pair of Anglo–Indian bureau–cabinets (late 18th century), Vizagapatam. Christie’s Paris: estimate €60,000–€100,000

The three-day sale (12–14 September) at Christie’s Paris of the collection of the renowned Argentinian interior decorator Alberto Pinto (1943–2012) reveals his passion for domestic ceramics of a quite different kind. A man who served up grand goût interiors for his wealthy international clients, he also entertained in extravagant formality at home. To that end, he gathered quantities of antique table linen, glass and silver, and also assembled grand porcelain dinner services as well as commissioning copies of others, including two famous gala services made for Catherine the Great (their modest estimates, beginning at €2,500, suggest that they are being sold for far less than he would have paid for them). Among his furniture is a pair of elegant Anglo-Indian ivory bureau-cabinets, made in Vizagapatam around 1786, decorated with engraved panels of villa landscapes, trees and flowers, and surrounded by borders of scrolling foliage (estimate €60,000-€100,000).

From the September 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.