Anyone who enjoys visiting British churches and cathedrals will soon learn to identify stained glass by Charles Eamer Kempe (1837–1907). Helpfully, he often placed a wheatsheaf in one corner of his windows, a device taken from his family’s coat of arms, but in any case his fastidiously luxurious style is unmistakable. Swathed in robes of cloth of gold and damask, figures derived from late medieval English and north European sources pose elegantly under elaborate gothic canopies against landscape backdrops evoking Albrecht Dürer and Martin Schongauer. Most characteristic of all are the colours: deep olive greens, tawny yellows and silvery-grey whites with flashes of ruby red.

Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale (1903–05), C.E. Kempe & Co. Royal Collection Trust, on permanent loan to the Stained Glass Museum, Ely

From its beginnings in the late 1860s to its closure in 1934, the Kempe firm installed windows not just throughout Britain but also beyond – there are, for example, major schemes in Bombay and Washington. A catalogue of Kempe glass published in 2000 runs to 396 closely printed pages. The firm also designed wall decoration, embroidered textiles, monuments and church furniture. This ubiquity helps to explain why in his magisterial two-volume history of the Victorian church Owen Chadwick pronounced that the art of stained glass ‘attained its Victorian zenith, not with the aesthetic innovations of William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, but in the Tractarian artist Charles Eamer Kempe’.

Not surprisingly, Kempe’s success provoked a reaction. The fact that he drew almost nothing himself and simply presided over accomplished but largely uncredited artists producing glass in a recognisable house style was well understood – not least because the firm was able to carry on in exactly the same way after he died. For historians of stained glass the contrast with Arts and Crafts windows, in which the artist-designer was involved in every stage of manufacture, is painfully obvious. ‘By the end of the nineteenth century’, writes Martin Harrison in his standard history of the medium, Victorian Stained Glass (1980), the work of Kempe’s firm ‘had become increasingly stereotyped’, with figures that were ‘flabby and over-bejewelled, flashy and mannered in draughtsmanship’.

It is much to the credit of Adrian Barlow, in his excellent new book, Kempe: The Life, Art and Legacy of Charles Eamer Kempe, that he faces this sort of criticism head-on – indeed, he cites even more examples. Among Kempe’s circle of close friends was the writer A.C. Benson, who recorded in his diary that the affection he felt for Kempe did not extend to his glass, which he regarded as a narcissistic series of self-portraits: ‘we do not want unadulterated Kempe everywhere – we don’t want Mr Kempe as St Peter […] talking to Mr Kempe as St Andrew – with two Mr K’s walking in the distance; and Mary Magdalene (as Kempe shaved and femininised) falling to the ground under a weight of Turkey carpets’.

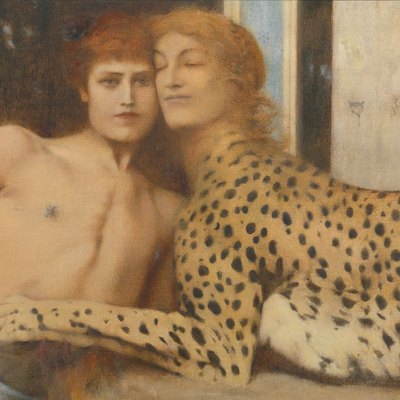

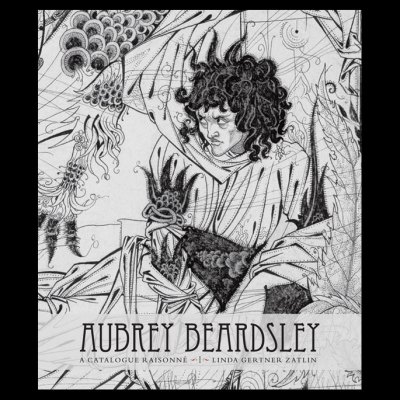

Although it is possible to counter such criticism partially by drawing attention to the often beautiful detail in some of Kempe’s late windows, a more fruitful line of defence is to see his glass in a wider artistic context. As Barlow demonstrates, Kempe’s early work, more delicate and less mannered than his later windows, is an expression of the Aesthetic Movement in its religious aspect, as his characteristic ‘greenery-yallery’ palette makes plain. In the 1880s Aestheticism evolved into the Decadent art of the fin de siècle, which – with the exception of Aubrey Beardsley’s work – is not usually regarded as having any significant expression in the graphic arts in Britain. As Benson implies, Kempe’s figures are remarkably sexless (though Barlow points to one significant exception in the nude boys who populate the glass in Kempe’s home, Old Place at Lindfield, Sussex, perhaps a clue to his sexuality). Yet in its stifling airlessness and emotional remoteness Kempe’s late ecclesiastical glass shares something of the mood of not just Beardsley’s art but also that of such European Symbolist and Decadent painters as Gustave Moreau and Fernand Khnopff.

That comparison may seem a bit farfetched, but Kempe’s work does at one point intriguingly intertwine with a major Symbolist artist, the sculptor Alfred Gilbert. The comparison has not previously been made, partly because almost no art historian bothers to look at stained glass; but also because the link between Kempe and Gilbert is through the royal family, and it is a near-universally accepted belief that after the death of Prince Albert there was no interesting royal patronage of the arts for almost a century. Despite his playboy reputation, Edward VII was High Church in outlook. The main influence on his religious beliefs was probably his wife, Alexandra, but he also owed something to the leading Anglo-Catholic layman, Charles Wood, 2nd Viscount Halifax, who had been a member of his household and was a good friend of Kempe. As early as 1876, Edward recommended Kempe to his sister Princess Alice, Grand Duchess of Hesse, to provide glass for the ducal mausoleum at Darmstadt in memory of her two-year-old son Friedrich.

St George (c. 1901–10), Alfred Gilbert. Photo: © Musée d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

Edward may have recalled the success of this commission when he was faced with a similar tragedy: the death in 1892 of his eldest son, Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale. As is well known, Edward and Alexandra commissioned from Gilbert the monument in the Albert Memorial Chapel at Windsor Castle, one of the high points in the history of British sculpture. Less well known is the memorial window they commissioned from Kempe for Buckingham Palace: damaged in the Second World War, it is now on permanent loan to the Stained Glass Museum at Ely. Albert Victor is represented as St George in Kempe’s familiar idiom. A comparison with Gilbert’s figure of St George sculpted for the Windsor monument in 1895, of which several versions exist, is telling: Gilbert’s statuette may rightly be thought of as the greater work, but it inhabits the same artistic world.

The coffin of Queen Alexandra at Sandringham Church, Norfolk, in the chancel redecorated by C.E. Kempe and Co. following the death of Edward VII in 1910 (photo: 1925). Private collection/Prismatic Pictures/Bridgeman Images

After Edward’s death in 1910, Alexandra commissioned the Kempe firm – by then run by Kempe’s cousin and heir, Walter Tower – to redecorate the chancel of the parish church at Sandringham, Norfolk, in the king’s memory. A scheme of astonishing sumptuousness, it includes a solid silver altar front and reredos as well as painted decoration and glass. The work of Kempe’s firm is here juxtaposed with that of Gilbert, since the chancel is the setting for a version of the sculptor’s St George, made in white metal and ivory for Edward and Alexandra as a private memorial. With its combination of precious metal and dense pattern the chancel might seem more at home in Secession Vienna than in rural England. It is undoubtedly a long way from Kempe to Klimt, but the links are there for those who look with unprejudiced eyes.

From the December 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.