A wealth of standout pieces dating back more than a thousand years are on display at Masterpiece London, revealing China’s illustrious and influential cultural legacy.

This selection was first published in Masterpiece London magazine 2014, in association with Apollo.

Garniture of three vases (c. 1768), Sevres porcelain with ormolu mounts. Pelham, London

Although this porcelain garniture was manufactured at Sèvres, the forms are based on antique Chinese bronze vases in the collection of the Chinese emperor Qianlong. In 1767 the factory had been presented with an engraved catalogue of the emperor’s collection by a French Jesuit missionary based in Beijing. The deep turquoise colour simulates Chinese porcelain, and was part of a very limited experiment by Sèvres to directly imitate Chinese production rather than reinterpret it.

Chest on chest, Chinese (c. 1720) Frank Partridge, London

This unique early 18th-century Chinese lacquer chest on chest is exceptionally rare. Its painted scenes are of extraordinary quality and depict exotic buildings within a landscape. All four drawers display similar motifs. This elegant piece is finished off by a central hanging acorn finial, standing on four circular legs joined by a shaped stretcher terminating in bun feet.

This unique early 18th-century Chinese lacquer chest on chest is exceptionally rare. Its painted scenes are of extraordinary quality and depict exotic buildings within a landscape. All four drawers display similar motifs. This elegant piece is finished off by a central hanging acorn finial, standing on four circular legs joined by a shaped stretcher terminating in bun feet.

Hairpin, Chinese, Ming dynasty (1368–1644) Sue Ollemans Oriental Art, London

This finely worked gold hairpin is in the form of pagodas settled into a floral filigree landscape. It is similar to those excavated in 1958 from an imperial Ming tomb in Nancheng Xian, Jiangxi Province, and now currently in the National Museum of China, Beijing. The reverse is also an outstanding example of filigree floral work, resulting in an object that is both technically accomplished – it displays the very highest of the goldsmith’s skills – and yet light enough to wear.

This finely worked gold hairpin is in the form of pagodas settled into a floral filigree landscape. It is similar to those excavated in 1958 from an imperial Ming tomb in Nancheng Xian, Jiangxi Province, and now currently in the National Museum of China, Beijing. The reverse is also an outstanding example of filigree floral work, resulting in an object that is both technically accomplished – it displays the very highest of the goldsmith’s skills – and yet light enough to wear.

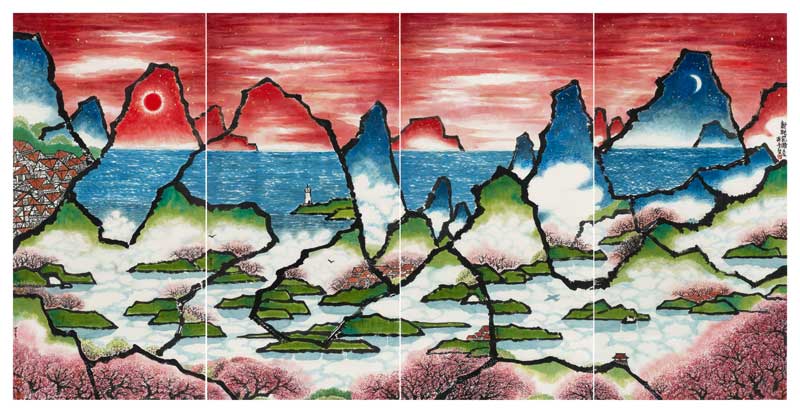

Peach Blossom Spring Rediscovered (2012), Lo Ch’ing. Michael Goedhuis, London

Born in Qingdao in 1948, Lo Ch’ing is a poet, painter and calligrapher. At an early age, he learned the court tradition of classical ink painting from the master Pu Ru, a member of the Manchu (Qing) imperial family. He is a major innovator of the genre, creating a new visual vocabulary that deconstructs the classical forms of Chinese landscape by introducing abstract and geometric elements, as well as unexpected contemporary motifs.

Born in Qingdao in 1948, Lo Ch’ing is a poet, painter and calligrapher. At an early age, he learned the court tradition of classical ink painting from the master Pu Ru, a member of the Manchu (Qing) imperial family. He is a major innovator of the genre, creating a new visual vocabulary that deconstructs the classical forms of Chinese landscape by introducing abstract and geometric elements, as well as unexpected contemporary motifs.

Tripod table, Chinese, c. 1720. Ronald Phillips, London

This early 18th-century Chinese tripod table has a triangular tip-up top and is one of only three examples known. One was formerly in the Mary and Leigh Block Collection in Chicago, and the other one is illustrated in the Dictionary of English Furniture and was made for the Tower family of Weald Hall, Essex. It was designed for a three-player card game called ‘hombre’, which originated in Spain and was popular in Europe during the period.

This early 18th-century Chinese tripod table has a triangular tip-up top and is one of only three examples known. One was formerly in the Mary and Leigh Block Collection in Chicago, and the other one is illustrated in the Dictionary of English Furniture and was made for the Tower family of Weald Hall, Essex. It was designed for a three-player card game called ‘hombre’, which originated in Spain and was popular in Europe during the period.

Bactrian camel with cargo, Chinese, Tang dynasty (618–906). Ariadne Galleries, New York

This exceptional Bactrian camel is a testament to the wealth of the Tang period. The camel’s load suggests the abundance of goods travelling to and from the West, while the sheer size and skill of the piece hints at the wealth of the owner. Its lifelike appearance is enhanced by the distinctive tri-colour glaze that is characteristic of the finest of Tang dynasty ceramics. A fine and lively example of its type, a comparable piece is held by the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

This exceptional Bactrian camel is a testament to the wealth of the Tang period. The camel’s load suggests the abundance of goods travelling to and from the West, while the sheer size and skill of the piece hints at the wealth of the owner. Its lifelike appearance is enhanced by the distinctive tri-colour glaze that is characteristic of the finest of Tang dynasty ceramics. A fine and lively example of its type, a comparable piece is held by the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

A pair of ‘Chinese’ display cabinets (c. 1755–65), attributed to Vile & Cobb. Apter-Fredericks Ltd, London

These outstanding cabinets, attributed to royal cabinetmakers Vile & Cobb, are manufactured almost entirely from two exotic woods chosen for their contrast: padouk, originally bright purple (as may still be seen where the shelves meet the backboards), and manchineel, a light yellow colour. These two woods are combined in the carving, the pierced and blind fretwork, the layered ‘roof tiles’, the herringbone banding and even the structural elements.

These outstanding cabinets, attributed to royal cabinetmakers Vile & Cobb, are manufactured almost entirely from two exotic woods chosen for their contrast: padouk, originally bright purple (as may still be seen where the shelves meet the backboards), and manchineel, a light yellow colour. These two woods are combined in the carving, the pierced and blind fretwork, the layered ‘roof tiles’, the herringbone banding and even the structural elements.

Masterpiece London takes place in the South Grounds of the Royal Hospital Chelsea, London, from 26 June–2 July.

This selection was first published in Masterpiece London magazine 2014, in association with Apollo.