When the artist Taro Hattori was a child, he used to play with his mother’s treadle sewing machine, pushing its foot pedal back and forth and imagining the motion carrying him on long journeys through snowy landscapes he had read about in books.

‘This repetitive motion was soothing to me, almost lullaby-like,’ says Hattori, who drew on that memory for an artwork in a group exhibition at SOMArts in San Francisco, ‘Sounds Like Home: Longing and Comfort through Lullabies’ (until 22 August). His installation Treadling A Lost Journey (2021) invites visitors to use a vintage treadle machine to play back recordings of people singing songs that remind them of the losses they have experienced.

Lullabies from Russia, Iran and Japan were among the songs that emerged during this collection process, says Hattori. But his piece also speaks to the undercurrent of melancholy in the songs that parents and caregivers around the world have softly crooned to restless children for thousands of years.

Treadling a Lost Journey (2021), Taro Hattori. Installation view of ‘Sounds Like Home: Longing and Comfort Through Lullabies’, SOMArts Cultural Center, San Francisco, 2021

Though lullabies in English were not widely distributed in written form until the emergence of children’s literature as a commercial genre in the 18th century, one of the first recorded lullabies was etched on a Babylonian cuneiform tablet around 2000 BC. Called ‘Little Baby in the Dark House’, it warns of the fate that may befall the child who has ‘disturbed the house god’ with its crying. In a lecture in 1928, the poet Federico García Lorca described his attempts to ‘collect lullabies from every corner of Spain’, musing on how his country ‘utilises its saddest melodies and most melancholy texts to tinge her children’s first slumber’.

‘Lullabies are messages to children, but also therapy for the caregiver; they can reflect their pain, their sorrow, their anxieties about the future,’ says Bengu Gun, who co-curated the ‘Sounds Like Home’ exhibition with her twin sister, Duygu Gun. The sisters say they were inspired by their family’s history of displacement from Greece to Turkey and their interest in music as a connecting force across cultures. ‘Lullabies are the most basic, most common song form in every culture. Even if we don’t understand the lyrics in a language, you understand the song is a lullaby,’ says Duygu Gun. Yet that universality is counterbalanced by a strong cultural specificity, both in people’s memories of lullabies and in the songs themselves.

‘There’s a lullaby from Pakistan where the mother sings, “Oh, you are your mother’s gravedigger,”’ says artist Husniya Khuyamyorova. ‘It sounds harsh and weird in English, but the meaning is “I want you to grow up and get old, to get to be an age where I can die and you can bury me” – it’s a wish for the child to live a long life.’

Videos from Khuyamyorova’s Lullabies of New York series (2017) show mothers from many cultures singing to their children as part of a project helping to preserve endangered languages and traditions among the city’s migrant communities. Supported by the Brooklyn Arts Council, the Lullabies of New York Project has trained artists, journalists, youth and other ‘citizen folklorists’ to collect and record lullabies sung within their own communities using phones, cameras and ethnographic interviews.

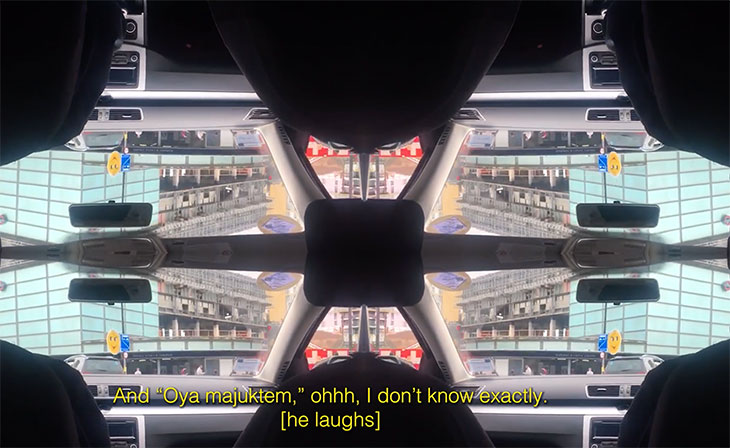

Still from Sleepdust: Uber Drivers Singing Lullabies (2019–21), Ceyda Oskay

In Sleepdust: Uber Drivers Singing Lullabies (2019–21), the artist Ceyda Oskay pairs a kaleidoscopic video of a ride through London with an audio recording of her talking with some of the city’s immigrant Uber and black cab drivers about lullabies. The snippets of conversation are as fragmented as the men’s memories of songs from their childhoods. ‘The experience of forgetting is part of migration as well,’ says Oskay. (An audio version of Sleepdust will be exhibited in London in September as part of the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition.)

The fragility of a tradition typically transmitted orally through the generations rather than being recorded or written down is compounded not only by migration but more recently by Covid-19. The pandemic has separated families from their older relatives, and – as pictured in photographer Hannah Reyes Morales’s series Living Lullabies (2020) – required some health-worker parents to stay physically apart from their own children.

‘The pandemic raised the question, how are we going to soothe each other when we can’t even touch each other?’ says Duygu Gun. Daniel Konhauser, a composer as well as an artist, points towards one potential answer with his interactive works Optical Score (2021) and Invisible Theremin (2021). They allow visitors to participate in digitally generating lullabies by rocking a small cradle in the gallery with a foot pedal or waving a hand in front of ultrasonic sensors.

Optical Score (2021), Daniel Konhauser. Installation view of ‘Sounds Like Home: Longing and Comfort Through Lullabies’, SOMArts Cultural Center, San Francisco, 2021

Nooshin Hakim had already grappled with the challenge of providing remote comfort in 2015, when resurgent violence in the Middle East brought back memories of her childhood in Iran. On summer nights, the artist’s family would gather on the roof of their home, watching lights in the sky that might be stars, or the first signs of an aerial attack. Recalling the comfort she derived from her mother’s singing during air raids, Hakim collected sung lullabies from people all over the world and had the recordings delivered to children displaced by war.

She later converted some of the recordings into punch cards that can be fed through a hand-cranked music box in her installation 100 Lullabies (2019). ‘We are usually bombarded with so much sound, but the music box creates a more one-to-one, intentional listening experience,’ Hakim says. Much like the lullaby itself.

‘Sounds Like Home: Longing and Comfort through Lullabies’ is at SOMArts, San Francisco, and in a virtual gallery until 22 August 2021.