It was Charlemagne who drove the development of musical notation. Crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 800 AD, he set out to conquer and unify, using the chant and liturgy of the Church as one tool to encourage conformity. Some scholars suggest that the earliest Western musical notation in the form of neumes, written above the words to be sung, was created in Metz around the time of Charlemagne’s coronation, to ensure that Frankish church musicians replicated the performances of Roman singers. But it was Guido of Arezzo, a Benedictine monk who arrived in that city around 1025, who is generally credited with inventing the Western system of notation. His four-line stave, marked with square notes (still used to notate Gregorian plainchant), led, in around 1200, to the five-line stave we use today. As Guido wrote in one of his many books: ‘I have determined to notate this antiphoner, so that hereafter through it, any intelligent and diligent person can learn a chant.’

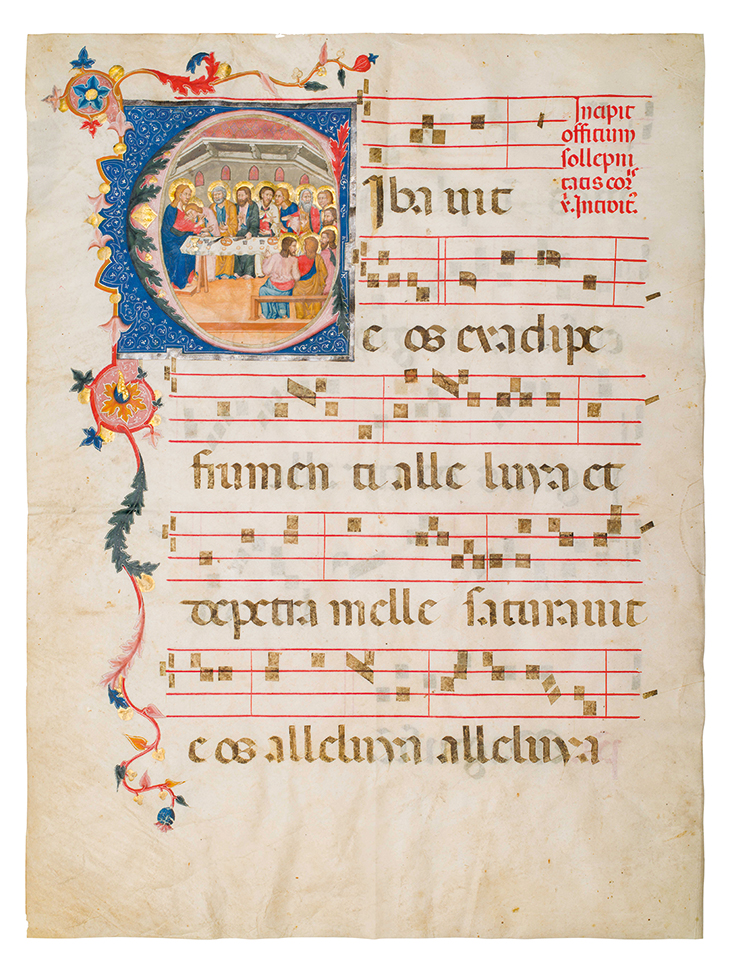

So important was Guido’s system to medieval Christianity that the volumes of music that resulted were lavishly decorated. Across monasteries in Europe, huge choir books were created from vellum sheets, the most splendid of which incorporated illuminated initials in bold colours and gold leaf. These were painted by leading artists, many of whose names are recorded. The sheets were bound in thick wood, covered with leather, and adorned with brass bosses. Some have clasps and ribbon or leather book markers. While antiphonaries contained the chants for Divine Office during the day to accompany prayers, readings from the Bible and psalms, graduals contained the chants for the Mass. In both, the contrast between the time-based music suggested by the pattern of notes and the silent image on a page is just one aspect of their appeal.

The invention of the printing press and the Reformation together forced a sharp decline in the production of illuminated manuscripts during the 16th century. However, these volumes, stored in monastic and private libraries, continued to be highly valued.

The modern market was triggered by vandalism. As Napoleon swept through Europe, his soldiers pillaged religious houses, seizing anything of value, including liturgical books. One person to benefit was Luigi Celotti (1759–1843), a Venetian abbot who bought the books and cut them up, keeping and selling on the miniatures and illuminations. It was the first sale dedicated to ‘Illuminated Miniature Paintings’ from his collection, at Christie’s auction house in London in 1825, that created a new field of collecting and inspired a new tribe of connoisseurs. William Young Ottley (1771–1836), who was invited by Christie’s to write the catalogue, bought many of the lots to add to his own collection, which was itself sold on through Sotheby’s in 1838. Not all of these illuminations were from choir books, reflecting the fact, still true today, that collectors are primarily interested in the sheet as an artwork, rather than in the music itself. T. Robert Burke, whose notable collection of Italian miniatures is on deposit at Stanford Libraries, has described his excitement when he realised he could acquire ‘paintings by notable Renaissance artists that had been commissioned as part of the decoration of these several-hundred-year-old manuscripts’.

Leaf from a set of eight choir books (1470s–80s), San Sisto, Piacenza. Christie’s London, £657,250 (for the set)

According to Sandra Hindman, president and founder of Les Enluminures and a leading scholar and dealer in the field, the market today breaks down into three parts. At the top end are the very rare examples of intact choir books. Then there are the cut sheets or individual miniatures. Import duties on manuscripts entering Britain in the 19th century were assessed by weight, encouraging the habit of cutting pages. As Hindman points out, ‘The practice is analogous to the cutting apart of gold ground paintings, which today circulate as single panels, predellas, wings separated from the altarpiece, and so on.’ And then there are the smaller ‘missals, notated psalters, tropers, and especially for the late Middle Ages, processionals’, which are not dramatically illuminated. ‘The collectors who buy single leaves and cuttings are typically interested in them for their “art”,’ Hindman suggests. ‘The collectors who buy whole choir books are typically book collectors.’ In terms of value, Hindman explains, ‘An initial or a sheet with a painting by a major artist (Lorenzo Monaco, Fra Angelico, Giovanni di Paolo) is worth a great deal of money in good condition (probably between $500,000 and $1m). An entire choir book could be worth the same price.’ A good provenance – either a distinguished collection or from a known book or library – can boost value. Generally prices have risen at the very top end, while remaining steady in the middle. Hindman adds, ‘You can acquire a pretty, totally haveable music initial for as little as $50,000.’

A complete graduale festivum (c. 1500), workshop or follower of Cosmè Tura, Ferrara. Antiquariat Bibermühle, €165,000

Sophie Hopkins, a manuscripts and archives specialist at Christie’s, cites the sales in London in 2015 of a rare survival cut from a 12th-century German troper, an ‘R’ illuminated with Christ emerging from his tomb, for £50,000 (estimate £40,000–£60,000), and in 2008 of a set of famous choir books from the Benedictine monastery of San Sisto in Piacenza (second half of the 15th century) for £657,250. Hopkins comments, ‘The demand for complete codices – choir books preserved as close to their original state as possible – is notably strong; examples from 14th- and 15th-century Italy are particularly prized.’ Christie’s will offer a number of choirbook leaves in its upcoming sale of valuable books and manuscripts, scheduled to take place on 15 July at King Street.

Leaf from a gradual depicting the Last Supper (c. 1330–40), workshop of Vanni di Baldolo, Perugia. Dr Jörn Günther Rare Books, €85,000

Heribert Tenschert of Antiquariat Bibermühle, based in Ramsen, Switzerland, deals only in complete volumes: ‘This is my conditio sine qua non.’ He currently has available ‘a fine graduale festivum from Ferrara of c. 1500, by a follower of Cosmè Tura’ (€165,000), and a massive 16th-century gradual from Spain. Jörn Günther, meanwhile, a passionate collector and dealer in illuminated manuscripts, who is based in Basel, Switzerland, has a number of fine sheets available. He remarks on the major collections established over the last 20 years, from the Getty in Los Angeles to the McCarthy Collection in London. This has made finding top-quality material all the harder. Günther notes that besides collectors in North and South America and in Europe, there has been strong interest more recently from Japan. He adds, ‘All my clients find these antiphonals very calming. If you allow yourself to enter this world, where there was a lot of contemplation, it is such a counterpart to our contemporary world, with all its busyness.’

From the June 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.