From the April 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), whose father, Charles Lewis, founded the jewellery firm Tiffany and Co., took his time to find his métier. Trained as a painter and a designer, he built a lucrative interior design practice in the last years of the 19th century, undertaking a dazzling refurbishment of the White House in 1882. But Tiffany’s primary passion was glass, and in 1878 he opened his first glass studio in New York. Experimental and inventive, here he pioneered the special varieties of glass – opalescent glass, iridescent Favrile glass (patented 1894), streamer glass, fracture glass, streaky glass, ring mottle glass, ripple glass, drapery glass – that he needed for his stained-glass projects. In December 1885 he established the first Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, developing a range of leaded-glass lamps, blown vases, mosaic and stained-glass windows. It is the products of this enterprise, renamed Tiffany Studios in 1902, that captivated the American public until his death in 1933, and remain much sought after, primarily in the United States.

Pebble table lamp (c. 1901–04), Tiffany Studios. Christie’s New York, $537,500

Pond Lily table lamp (c. 1903), Tiffany Studios. Christie’s New York, $3.4m

European museums and collectors bought Tiffany’s works from the Paris-based dealer Siegfried Bing, who pioneered the market in art nouveau between 1896 and 1902. The company won gold medals at World’s Fairs in Paris, St Petersburg and Turin between 1900 and 1902. But interest faded in Europe as art nouveau was superseded by art deco and modernism; and it is only in the last five years that signs of revival have been seen, in both Europe and Asia. Notably, a subtle, shimmering Pond Lily lamp, which achieved a world auction record for a work by Tiffany Studios in December 1989, fetching $550,000 at Christie’s New York, confirmed its record-breaking status in December 2018, also at Christie’s New York, selling for $3.4m (est. $1.8m–$2.5m) to an international buyer. The direct underbidder was also international. Daphné Riou, head of design at Christie’s New York, says, ‘There is a steady and strong market, especially for exceptional works.’ She cites the sale of ‘Important Tiffany from the Collection of Mary M. and Robert M. Montgomery, Jr’ on 11 December 2020, which totalled almost $4m for 34 lots, 100 per cent sold, for an average of $116,654. The second-highest achieving lot was a rare Pebble lamp from c. 1901–04, using a glass technique pioneered in 1888. Half the shade is composed of sliced quartz pebbles, like those found on the beach by Tiffany’s Laurelton Hall estate on Long Island. Estimated to achieve $100,000 to $150,000, it sold for $537,500.

Wisteria lamp (c. 1902), Tiffany Studios. Macklowe Gallery (in excess of $1m) Photo: Tony Virardi for Macklowe Gallery

Tiffany first gained fame for his stained-glass windows, but it is these jewel-like, vibrantly coloured and unabashedly naturalistic lampshades, with their elaborate bronze bases, which Tiffany began to produce in 1893, that have become iconic. A particular fertile period from 1897 to 1909 produced many of the most famous patterns – including the complex, intensely blue Wisteria lamp, the purple, orange and teal Dragonfly lamps, and the Pond Lily lamp. This era coincides with the last period of employment of Clara Driscoll (1861–1944), head of Tiffany’s Women’s Glass Cutting Department. A chance discovery in 2005 of a stash of letters revealed that she had not only played a critical role in maintaining the standards of craftsmanship at the company, but had also designed many of the most sought-after models, including Wisteria, Arrowhead, Dragonfly, Peony and Poppy. Beth Vilinsky, a Tiffany expert who joined Phillips New York as senior international design specialist in February, notes, ‘Tiffany relied on the eye of the women in the studio to select the tiles for the patterns. Although the shades were built in moulds, according to patterns, so should match up identically, glass selection and craftsmanship vary greatly.’

The difference in glass selection can make a threefold difference to the price. Another factor is the relationship of base to lamp. While for many models Tiffany Studios sold shades and bases separately, some more expensive models had specific, sculptural stands to form an organic whole. A Wisteria lamp – which would have cost an exorbitant $400 when created in 1905, partly because of the more than 2,000 glass tiles required for its construction – sold for $525,000 at the Montgomery sale at Christie’s in December 2020. It came with its original base, shaped like a tree trunk. In December 1997, Christie’s sold a splendid, rare Lotus Flower lamp (c. 1900–10) with an unusual mosaic base for a then record-breaking $2.8m. The following year, Phillips sold a spectacular centrepiece Peacock lamp with an elaborate, wide-spreading base, believed to have come from Louis Tiffany’s own residence, for $1.9m.

In 1919 Tiffany ceased to play an active role in the company, and after his death his glass fell out of favour. Vilinsky suggests that a Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design) exhibition in New York in 1958, which presented Tiffany’s lamps, blown glass and paintings, sparkled a revival of interest; the publication in 1964 of Robert Koch’s Louis C. Tiffany: Rebel in Glass and the sale in 1966 of the Coats-Connelly Collection of Tiffany Favrile glass at Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York added impetus. So did the exhibition ‘Masterworks of Louis Comfort Tiffany’ – including the whole range of the firm’s most spectacular lamps, windows and household glassware – which opened at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. in 1989 before travelling to the Met in New York and four museums in Japan. There are passionate collectors across the United States, the private broker Dennis Tesdell notes: ‘Some of the more advanced collectors can have 30 to 50 or more lamps in their collection.’ If the floral patterns are more sought after than geometric patterns, he adds, ‘the more rich and vibrant colours are favoured’. Tesdell confirms that condition is important, though there is tolerance for minor repairs.

Peacock window (c. 1890–95), Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company. Lillian Nassau ($750,000)

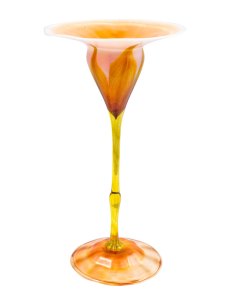

Arlie Sulka, director of Lillian Nassau in New York, credits Nassau, her mentor, with rekindling the market. There are collectors for all aspects of Tiffany’s output, including stained-glass windows – Sulka has an early Peacock window, c. 1890–95, probably designed for a landing, at $750,000 – and blown glass. ‘I am particularly fond of the blown glass,’ she says: ‘It is spectacular, innovative and was very influential. As soon as we put a piece on our website, it goes.’ She adds, ‘People look for Lava, Aquamarine and Cypriote glass pieces,’ inspired by Roman glass, and the iridescent ‘Jack in the Pulpit’ vases. She has a 51cm-tall gold version available, price on application.

Floriform vase (1903), Tiffany Studios. Kunsthandel Kolhammer (€20,000)

The New York dealer Benjamin Macklowe advises that Tiffany blown glass is currently undervalued: ‘a fraction of the price it was five or six years ago.’ He says, ‘Mr Tiffany actually considered his blown glass to be his most important contribution to the field of art and it was his first and abiding love.’ Meanwhile in Vienna, Nikolaus Kolhammer of Kunsthandel Kolhammer reports a modest market in Europe for Tiffany blown glass among specialists in high-quality glass from around 1900 who appreciate Tiffany’s distinctive contribution to art nouveau: ‘The floriform vases – with calyx bodies – are so much more naturalistic than European examples.’ But half his finds return to America. Kolhammer warns buyers to take specialist advice: fakes are rife. Sulka confirms that in addition to frank imitations, ‘People have been faking lamps since the 1970s.’ The marking ‘Tiffany Studios’ is no guarantee: ‘We advise people not to collect by signature. Collectors need to educate themselves.’ Caveat emptor!

From the April 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.