From the May 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1962 – around the time of his first solo show with Leo Castelli in New York, which sold out before it had even opened – Roy Lichtenstein said to his friend the artist Bruce Breland: ‘You know, it’s hard to believe, but I wonder how long it’s going to last.’

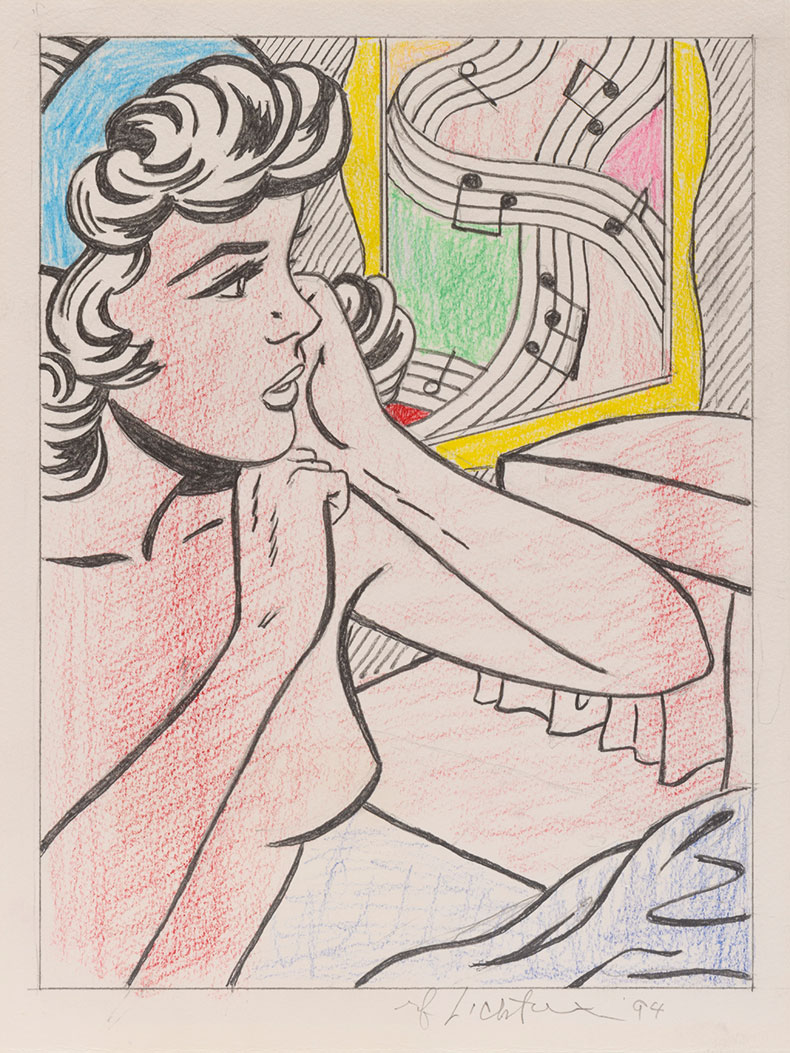

This year marks the centenary of Lichtenstein’s birth – and as it turns out, the robustness of Lichtenstein’s market still seems unassailable. In November 2014, Nurse (1964) – a masterful early painting, inspired by a comic-book image and employing the characteristic Ben-Day dots Lichtenstein lifted from commercial printing – sold for $95.4m at Christie’s New York, a record for the artist at auction.

Lichtenstein made his name with large-scale paintings, their immaculate surfaces of glossy oil paint and acrylic offering the illusion of mechanical reproductions. Yet his drawings, collages and prints have increasingly been understood as an essential part of his practice.

Lichtenstein’s capacity to maximise the psychological impact and formal intensity of imagery taken from comic books and commercial advertisements is evident in his studies for major paintings. But it is also there in the significant body of black-and-white stand-alone drawings he made between 1961 and 1968. Inspired by fragments cut from magazines, newspapers and telephone books, these focused largely on household items and comic-book scenes of war and romance.

Collage also became a significant step in Lichtenstein’s process, enabling him to shift visual elements around and test their effect before committing to a trial print or putting paint to canvas. He constructed these collages from a range of materials including foam, board, tape and polyester film. There is a similarly exuberant embrace of different materials in Lichtenstein’s printmaking. While Warhol largely stuck to silkscreen, Lichtenstein ranged from woodcut to etching, lithography and screenprinting, sometimes combining multiple print techniques in one image and experimenting with different materials to print on to.

Rachael White Young, co-head of the post-war and contemporary art day sale at Christie’s New York, says: ‘As with many artists, the profile of a collector of Lichtenstein’s works on paper is more exclusive, more nuanced. They tend to have a greater appreciation for the process, the concept, the insight into the artist’s mind that a study or drawing provides.’ Christie’s New York has achieved a number of outstanding results. The punningly titled Collage for Interior: Perfect Pitcher (1994) made $4.4m in May 2015 – matching the record for a work on paper set at Christie’s the previous November for Hot Dog, a black-and-white finished drawing of 1964 (both estimates $1.5m–$2.5m).

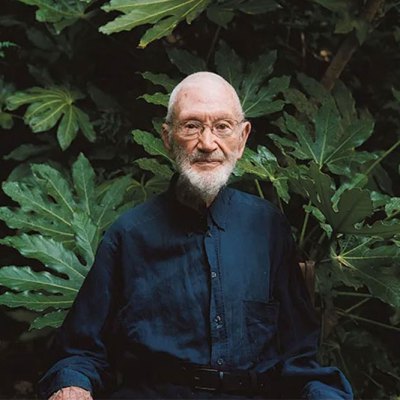

Nude with Joyous Painting (Study) (1994), Roy Lichtenstein. Phillips New York, $1.7m

More recently, Phillips New York fetched a mid-estimate $1.7m in December 2020 for Nude with Joyous Painting (Study) (1994) – a drawing related to a highly sought-after late series, it reprises an interest in the genre of the nude from much earlier in his career, while also directly reflecting his efforts to harness a sense of musicality in his art. In June 2021, Phillips sold his Collage for Interior with Painting and Still Life – completed in 1997, the final year of Lichtenstein’s life – for $1.4m (estimate $800,000–$1.2m). According to Scott Nussbaum, senior international specialist of 20th-century and contemporary art at Phillips New York, ‘The work continuously evolved over time – so there is a constant process of rediscovery.’ Nussbaum points out that Lichtenstein’s oeuvre was sufficiently extensive to ensure that there remains a continuous supply of his work today – though not so much as to exceed the very strong demand across the United States and Europe and, increasingly, East Asia. ‘There is a direct correlation between the commercial appeal of a study or collage and the value of the related painting,’ he adds. Stefan Ratibor, a director at Gagosian who has worked with the Lichtenstein estate for many years, argues that while collectors of works on paper used to represent a separate market, today a major drawing will make it into an evening sale. ‘A study for an amazing painting, fresh to market, in good condition: I would offer this to a global audience.’ He points to the fact that recent museum exhibitions – including the survey jointly organised by the Art Institute of Chicago and Tate Modern in 2012 – have shown studies and collages alongside famous paintings. While some collectors do pursue well-known imagery, Ratibor suggests that others look for less familiar series, such as the Water Lilies or the landscapes from the late 1960s and ’70s. Gagosian will mount a show of sculpture and works on paper in New York in the autumn, including a small study and a life-size collage of 1989 made in preparation for the sculpture Galatea (1990).

Barbara Castelli, director of Castelli Gallery, suggests that until recently some collectors found the collages less desirable, seeing them as technical tools rather than works of art in their own right. ‘Now they recognise that they are an interesting way to experiment with mark making.’ Similarly, while some collectors might be attracted to a very clean drawing – perhaps following Lichtenstein’s declaration that ‘I want to hide the record of my hand’ – others are drawn to the collages precisely because they reveal the artist’s fingerprints. Lichtenstein alternated between approachable and intellectual subject matter. Castelli suggests that, while ‘it used to be harder to sell a collage of a Chinese landscape or an entablature than a nude’, people now enquire after minimalist works of the 1970s: ‘The younger generation are challenging old views of what is iconic.’

Rhonda Long-Sharp, a dealer in Indianopolis, warns collectors to demand full documentation for any drawings or prints. She acquires only from the estate or Lichtenstein’s printers. Prints from the series of nudes completed in 1994 fetch $800,000 and upwards, but there is also strong interest in the Water Lilies, the Reflection series (1990) and the prints of 1965. Long-Sharp Gallery is showing at Treasure House Fair in London this summer (22–26 June).

Bull’s Head (1973), Roy Lichtenstein. Cristea Roberts, London, $100,000 (for a set of three)

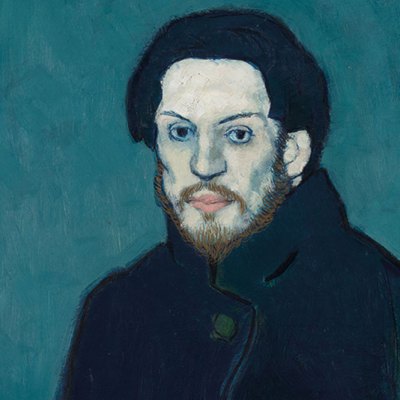

For David Cleaton-Roberts, senior director of London-based print gallery Cristea Roberts, ‘Printmaking was hugely important for Roy Lichtenstein. The graphic nature suited his style, but it also enabled him to reach a wider audience.’ The most sought-after prints today include the two images Lichtenstein contributed to the portfolios sponsored by the tobacco giant Philip Morris in 1965, 11 Pop Artists, and complete sets of series like the landscape series or the bull series. There is inevitably a premium on having a complete, ‘evenly numbered’ suite of prints (from the same numbered edition). Cristea Roberts has a complete set of the seven prints from Lichtenstein’s Landscapes series (1985); in perfect condition, they are priced at $1.2–$1.5m. The gallery also has a set of six Bull Profiles and three Bull’s Heads, both completed in 1973 and inspired by Picasso’s famous series of lithographs depicting the same subject; the Bull’s Heads are offered at $100,000 for the three. As ever, rarity and condition are key to value.

From the May 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.