Enamelling – the firing of ground coloured glass on to metal – is an ancient technique. First recorded in the 13th century BC in Cyprus, it spread through ancient Greece into Europe, and was used extensively by the Celts in Gaul and in Britain. From the 6th century, Byzantine jewellers perfected the technique of cloisonné enamelling, dropping coloured glass into shapes created by soldered strips of gold, a skill carried by the Ostrogoths into Italy and by Visigoths to the Iberian Peninsula. In the first half of the 12th century, three distinct centres emerged in Northern Europe; in the Meuse Valley, Cologne, and Limoges. The workshops that sprang up used copper as the base, and the art of enamelling was carried to new heights. For Western Christendom, the techniques offered not only vibrantly coloured splendour for the many liturgical objects that filled churches and treasuries, but the process itself was seen as emblematic of the transformation of Christian souls through purgatorial fire.

Some collectors regard Mosan enamels as the apex of medieval enamelling, with their distinct palette, subtle shading, and graceful designs. Indeed the great collector Edmund de Unger, who established the renowned Keir collection, which was sold at Sotheby’s in 1997, set out to add Mosan enamels to the Limoges enamels he had purchased in the early 1970s from the Ernst and Martha Kofler-Truniger collection. (Even then, he reported that there was very little to buy of the highest quality.)

Châsse (c. 1220), Limoges, champlevé enamel over gilt copper on an oak core. Sam Fogg (£100,000)

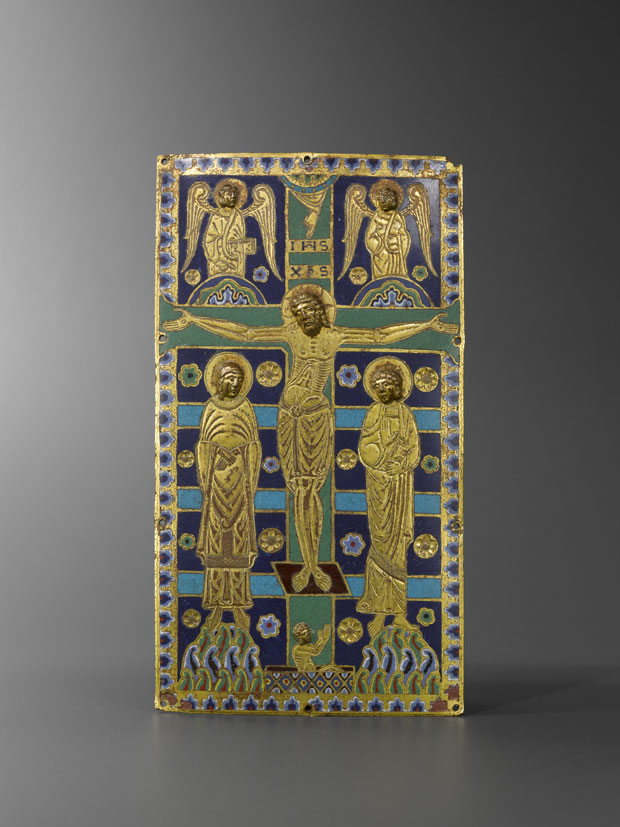

During the first half of the 12th century, under the patronage of local abbeys, craftsmen around Limoges began to perfect the champlevé technique of enamelling, engraving shallow beds in the copper into which the glass could be poured. Several firings were required to fuse the different colours, followed by further engraving, gilding, and polishing, but the technique ensured brilliance and a smooth, flush surface. Where Mosan pieces show enamelled figures against a gilded copper ground, the Limoges craftsmen preferred to place gilded figures against highly coloured backgrounds, including those with the characteristic scrolling vermiculé foliage. By 1170, Limoges enamels were the talk of Europe, aided by its place on the pilgrim’s route to Santiago de Compostela and links with Britain, after Eleanor of Aquitaine’s marriage to Henry II. They were often used to decorate reliquaries – saintly relics were popular at the time – such as the well-known Thomas à Becket châsses. By 1215, when Pope Innocent III decreed that all churches must have at least one Limoges-enamelled Eucharistic container, production had become systematised to meet demand, tailing off only in the second half of the 14th century.

Since the Romantic vogue for all things medieval in the early 19th century, these Romanesque enamels have been highly sought after by collectors. Alexander Kader, head of European sculpture and works of art at Sotheby’s, says: ‘What matters to collectors is that the object is early [pre-1200], that it has a great provenance and that it is in good, original condition.’ The market hit its peak in 1996 when the beautiful Becket Casket now in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum was bought by the Canadian collector Lord Thomson for £4.2m (before a high-profile campaign secured it for the nation); and the base of a candlestick achieved £4.4m – a record then for a medieval enamelled object.

Kader identifies two kinds of collectors, both almost entirely based in Europe and North America: the medieval specialist, who seeks liturgical objects – ‘a great book cover, a great pyx and a great châsse, maybe a crozier or cross, and a candlestick’; and the masterpiece collector, on the lookout for the one outstanding object that will combine with other treasures. Such an object might be the parcel-gilt Eucharistic dove of around 1200, which achieved $1.9m at Sotheby’s New York in June 2007. Christie’s specialist Donald Johnston reports that in 2011, in a sale in Paris, a brilliantly blue Limoges enamel book cover, depicting the Crucifixion and dated 1190–1200, achieved €517,000. In May last year, a plainer example fetched £80,500 at Christie’s London. ‘When a good piece comes up, people are interested,’ says Johnston.

Eucharistic Dove (c. 1200), Limoges, parcel-gilt copper and champlevé enamel. Sotheby’s New York, $1.9m

Matthew Reeves at Sam Fogg, a dealership in this field for many decades, comments that good pieces are increasingly hard to find outside museums. ‘You cannot expect pristine condition,’ he says. Collectors look for elegance of design and control over the enamelling process, together with the proportion of original enamelling and gilding remaining. For many collectors the cut-off date for the finest work is the mid 1200s. By the 1270s, when Isabella of Aragon was buried in a white marble tomb in St Denis, fashion had moved on. He has a fine book cover (£65,000), a châsse (£100,000), and a cross (£20,000), among other objects.

Marie-Amélie Carlier of leading French dealership Brimo de Laroussilhe comments that today’s collectors can acquire a gorgeous piece of medieval art for the relatively small amount of €10,000. She finds an active market in Europe and in the US, among both museums and private collectors. She currently has available a book cover, an apostle plaque and candlestick. New York dealer Anthony Blumka has a beautiful book cover depicting the Crucifixion on offer, dated to the early 13th century. ‘Prices have escalated dramatically for the most important objects,’ he says, owing to the paucity of top-quality material.

But as one market shrinks, another swells. Around 1470, the Limoges workshops developed a new industry: painted enamels. According to Antwerp-based dealer Bernard Descheemaeker, until 1545 these compositions, painted on copper plaques, were largely religious scenes used for private devotion, derived from Northern European engravings. Thereafter a number of talented enamellers (including Léonard Limosin, Pierre Reymond, Jean de Court [also known as Jean Court dit Vigier] and Suzanne de Court) developed techniques for enamelling plates, ewers, and tazzas, with scenes that were as often drawn from mythology and ancient history as from Christian texts. Grisaille became popular among Europe’s nobility, as interest in the antique spread through the continent. Quality then declined in the 17th century.

Book Cover (c. 1190-1200), Limoges, champlevé enamel on copper, engraved and gilt. Brimo de Laroussilhe (price undisclosed)

Since 2015 Descheemaeker has handled the impressive Thyssen-Bornemisza collection of Limoges painted enamels. The sale of Hubert de Givenchy’s exceptional collection in 1994 revived the market. ‘In the early 1990s, you could buy a plate for €2,000; now a nice 16th-century plate will cost between €20,000 and €25,000,’ he says. Currently he has available a magnificent covered tazza (1555–60) by Jean Court dit Vigier, decorated with the Triumph of Neptune and Amphitrite, for €185,000.

The high point of this rising market was the 2014 Sotheby’s London sale of six vivid panels representing scenes from Book VIII of the Aeneid, by the Master of the Aeneid (active c. 1530–35), which sold for £1.5m. The six had been in the collection of the Duke of Northumberland for many decades, and inspired brisk bidding, in this appropriately named Treasures sale.

From the January 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.