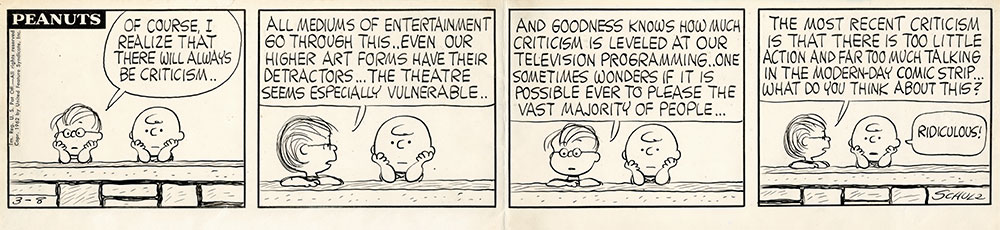

In a Peanuts strip from March 1962, Charlie Brown and Linus discuss the nature of criticism. Linus was the strip’s intellectual: a gentle, fragile child, the stripes on whose T-shirt were almost as wispy as the hairs on his head, and whose security blanket D.W. Winnicott wanted to use as an example of the transitional object. The two boys are leaning on a wall, as they often do when waxing philosophical. ‘Of course I realize there will always be criticism,’ Linus concedes. Television in particular and even ‘higher arts’ such as theatre can come in for a rough press. ‘The most recent criticism is that there is too little action and far too much talking in the modern day comic strip. What do you think about this?’ ‘Ridiculous,’ replies Charlie Brown.

Schulz Family Intellectual Property Trust. Courtesy the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center

The strip is displayed as part of ‘Good Grief, Charlie Brown!’, an exhibition at Somerset House exploring Peanuts’s cultural reach. One of the things the exhibition captures well is Charles M. Schulz’s touchiness. His sensitivity to criticism can seem at odds with the apparent simplicity of Peanuts: its ageless Midwestern idyll, where Charlie Brown, his friends and his beagle play baseball or ice hockey, or just shoot the breeze, all rendered in Schulz’s trademark – revolutionary – minimalist line, with an Esterbrook’s Radio 914 pen. But naivety in Peanuts went hand in hand with crankiness from its first appearance as a syndicated daily, in October 1950. Charlie Brown, more cherubic then than the frazzled everyboy he grew into, is seen approaching from a distance. ‘Well!’ says a watching boy called Shermy, ‘Here comes good ol’ Charlie Brown! […] How I hate him!’

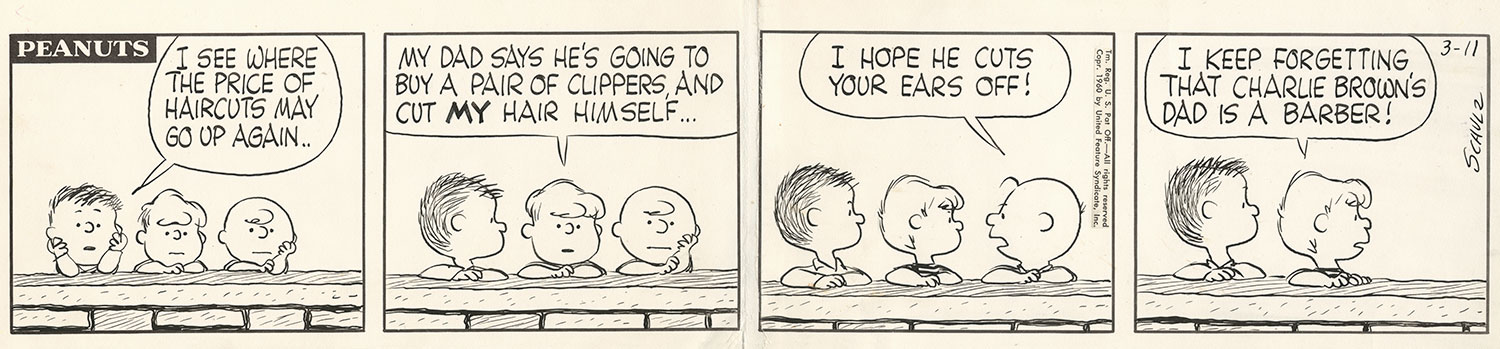

The exhibition, which stretches across two floors, begins with a series of displays drawing links between Schulz’s biography and his work. Peanuts strips are juxtaposed with Schulz family photos and mementoes as we learn that the cartoonist, born in Minneapolis in 1922, shared a love of comics as well as an obsessive perfectionism with his father, a Minnesotan barber; how Charlie Brown’s pet beagle Snoopy was based on Schulz’s childhood dog, Spike; that characters such as Linus and the Little Red-Haired Girl, for whom Charlie Brown nursed an unrequited and unrelenting love, were based on old friends and colleagues.

Schulz Family Intellectual Property Trust. Courtesy the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center

The keynote throughout these biographical vignettes is emotional overwroughtness. The first strip we encounter in the exhibition is from March 1960 and shows Charlie Brown leaning on a wall again, this time with Shermy and Schroeder, the musical prodigy more often seen hunched over his toy piano. The other boys complain about the price of haircuts; Schroeder says his dad will cut his hair to save money. ‘I hope he cuts your ears off!’ snaps Charlie Brown, then storms off. Schroeder watches him go: ‘I keep forgetting Charlie Brown’s Dad is a barber.’

As we move into the second section of the exhibition, which examines Schulz’s technical brilliance, a sense of his emotional insecurity remains. Mounted original strips demonstrate how he used the responsiveness of the Radio 914 to create environmental effects such as rain or snow with a few simple pen strokes, or how he used a thicker B-5 nib to letter Linus’s overbearing sister Lucy’s speech bubbles, ‘when she was doing some loud shouting’. That famous minimal line vibrated, though – both with a hand tremor, increasingly evident as he grew older, and with the conflicting, sometimes overwhelming emotions of his characters.

Installation view of ‘Good Grief, Charlie Brown! Celebrating Snoopy and the Enduring Power of Peanuts’ at Somerset House, London, 2018. Photo: Tim Bowditch

Schulz’s genius was to create a strip about children which only seems to explore adult themes if we pretend not to remember how confusing and humiliating it is to be a child, and only appears to be childish if we refuse to admit how vulnerable and clueless we can feel as adults. It makes sense, then, that even as a successful adult he continued to fret. And Peanuts was a big success. Schulz earned over $1bn from licensing the strip, which he drew himself until the final original frames appeared the morning after he died in 2000. On your right as you enter the gallery is a display case full of Peanuts merchandise: cuddly toys, mugs, board games, and Snoopy figurines. Snoopy as a viking; a mariachi guitarist; a Coldstream Guard.

The final section of the exhibition looks at the treatment of particular themes in Peanuts. Lucy – ‘the most terrifying character in the history of comics’, according to the journalist Christopher Caldwell – and the no-nonsense Peppermint Patty are presented as examples of Schulz’s unshowy feminism; Franklin, a new friend for Charlie Brown, who in 1968 became the first African American to appear in a mainstream American comic, as evidence of his engagement with civil rights. Elsewhere, Peanuts strips are displayed alongside the work of artists inspired by them. We find strips featuring the Psychiatric Help stand at which Lucy hawks questionable therapy for a few cents from her front yard, where other children might sell lemonade, near a print from 2018 by Mel Brimfield, in which images of the artist looking like a bewigged Charlie Brown disperse around a silhouette of Lucy, voicing anxious childhood memories. In a text box in the bottom-left corner of the work are the words ‘Mel Brimfield is nuts’.

Nuts: Episode 23: Remembrance of Things Past (2018), Mel Brimfield. Photo: Tim Bowditch

The dominant voice remains that of Schulz, and his neuroses. A documentary clip plays downstairs on a loop. At one point, Schulz mentions Woodstock, a yellow bird introduced to the strip in 1967, who becomes Snoopy’s best friend. Schulz makes glancing reference to criticism of the character, without elaborating that this is characteristic of a general sense among Peanuts fans that the strip declined as its focus moved away from the bleak humour of Charlie Brown’s human misadventures in its ’60s heyday to the whimsy of Snoopy’s animal world and his beagle fantasies (such as his alter ego, the First World War Flying Ace). Schulz asserts that Woodstock remains one of his favourite characters. You don’t write the same comic strip every day for nearly 50 years, facing down the critics who attend ‘all mediums of entertainment’ as Linus put it back in 1962, without being at least a bit stubborn.

‘Good Grief, Charlie Brown! Celebrating Snoopy and the Enduring Power of Peanuts’ is at Somerset House, London, until 3 March 2019.