At the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, Texas, where Doris Salcedo (b. 1958) is receiving the institution’s first annual prize, voices and glasses ring outside, while in the galleries, four or five sleekly dressed people stand still in the maze of Salcedo’s installation Plegaria Muda (2008–10). No one speaks; the room resembles a woodland cemetery. In the piece, large oblong tables are arranged in pairs: one upturned on top of the other, with a layer of soil between, long blades of grass pushing up here and there through the cracks in the upper table’s wooden belly. These are domestic objects as much as they are unmarked graves. They quietly commemorate the lives of at least 2,500 young Colombians killed by the army between 2003 and 2009 (Salcedo accompanied some of their mothers in the attempt to find and identify the bodies), as well as those of thousands of Americans lost to gang shootings on the streets of southeast LA, who kill and are killed in circumstances of violent anonymity, without proper mourning; they already exist in a state of ‘social death’.

Installation view of Plegaria Muda (2008–10), Doris Salcedo, at the Nasher Sculpture Center. Photo: © Kevin Todora/Nasher Sculpture Center; © the artist

Salcedo trained in sculpture in the mid 1980s at New York University (where Joseph Beuys’s notion of social sculpture became especially important to her), but, unusually among artists of her stature from outside the US and Western Europe, has continued to live and work in the place she came from, Bogotá. Over the years, she tells me, Colombia – which she has called ‘the country of unburied dead’ – has given her a sustained perspective, a ‘structure that allows me to understand what is happening everywhere’. What is happening everywhere, from US churches and elementary schools, to Brussels, to Pakistan, is what Salcedo (following Hannah Arendt’s early diagnosis of it in 1963), calls a state of undeclared civil war, in which ‘there are no longer soldiers and civilians, you can no longer locate a specific battlefront, but it could be anywhere.’ The political violence that has remained Salcedo’s subject throughout her career is defined in part by its borderlessness.

The sections of Plegaria Muda are more tomblike even than the untitled works Salcedo began making in the 1990s, where ordinary wooden furniture was burdened with concrete in which embedded pieces of clothing could be made out, often that of the victims of violence Salcedo meant to honour. Other works often contain fragments of bone and hair alongside the possessions. Yet their effect is sober rather than emotive, perhaps because of Salcedo’s method: she describes a long process of distillation in which she also draws, and reads philosophy and poetry, ‘so that when I begin a new piece I’m someplace else, not exactly the person I was before’. Though she spends many hours talking to the victims’ families, she is suspicious of any impulse to ‘just go for the sad story’. Once the individuals her work is based on ‘enter into your mind, they stay there’, she says, citing Elias Canetti’s claim to be haunted by thousands and thousands of victims. Still, ‘If you talk about these tragedies, of course everybody will be moved, but that’s not what I’m trying to do.’ She wants to maintain ‘some respectful distance’. (‘With my burned hand,’ she says, quoting Flaubert, ‘I write on the nature of fire.’) In a way, she is resisting both the narrative and the image. ‘There are some things you cannot say. There are many things you cannot show.’

Untitled (1998), Doris Salcedo. Courtesy Pérez Art Museum, Miami; © the artist

That distance allows Salcedo to make work that proceeds from addressing individual suffering to something more collective. Beginning with the testimony she gathers from people, which she allows to determine the material and formal qualities of the resulting work, she nonetheless wants to mute the specificity of their stories. Especially when seen in person, the works, not least Plegaria Muda, have a monumental quality, in which many lives seem to be subsumed into a larger pattern, and they also deliberately evoke a sense of what is lost or threatened ‘every time a violent act takes place’ – an essential humanity that Salcedo unselfconsciously indicates for me with a wave at the Vivaldi emanating from the hotel speakers near where we are sitting (What kind of humanity? I ask her; ‘That kind!’).

Installation view of Untitled, 2003, Doris Salcedo. Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York; photo: Muammer Yamaz; © the artist

Salcedo has created public works bearing witness to acts that might otherwise be forgotten, most spectacularly her slow-motion tumbling of some 280 old wooden chairs down the external walls of Colombia’s Palace of Justice on 6 and 7 November 2002. It was the anniversary of the army’s brutal attack on guerrillas who were occupying the Supreme Court in protest in 1985 – at least a hundred people were killed. (The chairs, like the wooden tables, are by now a familiar part of Salcedo’s visual and political language: in her untitled piece for the 8th International Istanbul Biennial in 2003, a tangled wall of them filled a vacant lot between two buildings, forming what she has elsewhere called ‘a topography of war’.) ‘I’m not buying the present as it’s being presented to me,’ she says. ‘I want to rethink it, and in order to do that I have to go and look at events in the past carefully.’ But her primary concern is not with revealing what’s hidden. ‘I don’t think anybody takes any trouble trying to conceal anything any longer,’ she says. ‘If you want to know what American contractors are doing in the Middle East, you can know. Nobody’s making an effort. Nothing is hidden. It’s no longer a secret. If you are exerting violence, you want it to be known, otherwise it would have no effect. If you want it to have an effect, it has to be shown. So, you find images of torture everywhere, from Abu Ghraib to a teeny tiny town in Colombia. It’s all on the web, for whoever is interested, for whoever cares.’

Salcedo allows herself a paradoxical combination of directness and indirection, and insists on keeping her political engagement strictly within the boundaries of the work itself, within the realm of art, which has its own rules (‘I’m not trying to be political or pedagogical outside the piece. Every one of my pieces contains what I need to say, and it is there.’). ‘It would be a trap to try to portray violence,’ she says, in any literal way. ‘Because violence is exerted whenever you show it, whether in art, or in cinema, or in reality. When you reproduce a violent act […] violence is being exerted and re-enacted once again, and I don’t think we need that.’

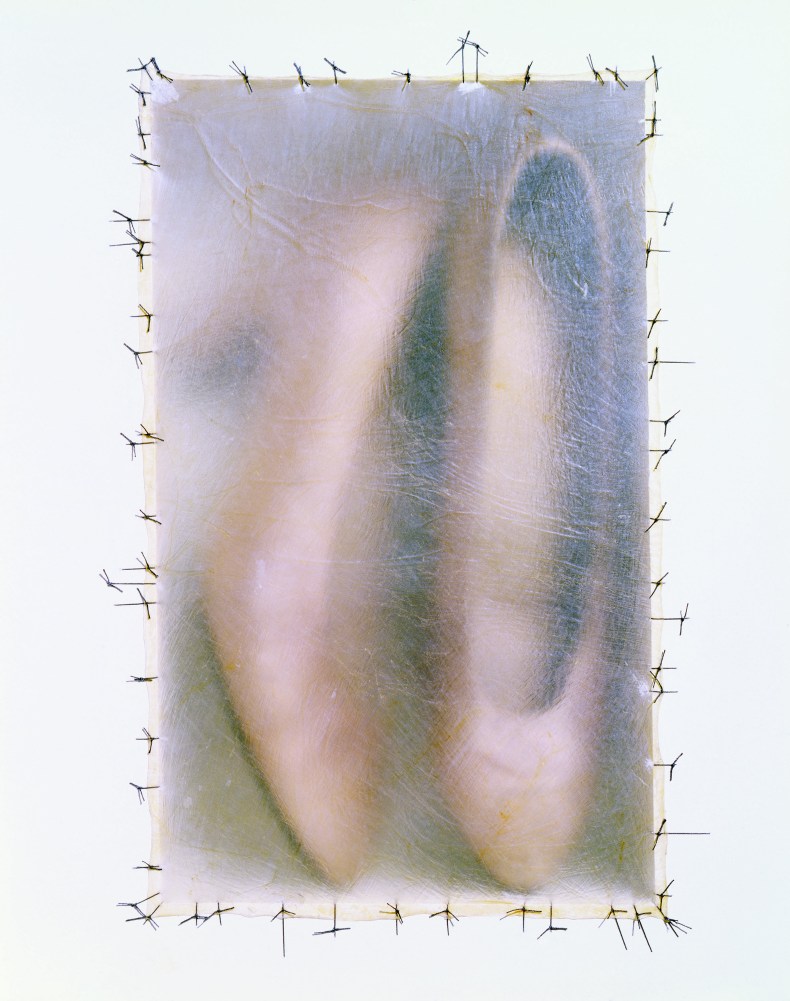

Installation view of A Flor de Piel (2011–12), Doris Salcedo. Courtesy Pérez Art Museum; © the artist

The violence she is concerned with, she notes, is inherently vulgar – and an art that attempted to represent it would risk being ‘pornographic or obscene’, a form of ‘hyperrepresentation’. Her work instead conceals the traces of physical violence (the embedded bone or hair) or represents it only by visual inference, as in a piece like A Flor de Piel (2011–12), whose formal simplicity and elegance redeems what could so easily seem either ghoulish or sentimental – a great mass of individual rose petals stitched together to form a cloth that spreads like spilled blood or a flayed skin. The untranslatable title idiom, which links skin and flowers, is used to describe an emotional state, which is raw and exposed. Salcedo’s attraction to metaphor is perhaps the first thing one notices in her work, and is key to the writers and philosophers she returns to most frequently over the years – she names Paul Celan, Gilles Deleuze, Alain Badiou, Jean-Luc Nancy, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Walter Benjamin – whose appeal for her has something to do with ‘the relation between poetry and politics’, and her inability to imagine one dimension without the other. Metaphor, of course, involves at least two forms of concentration, and that might be as useful a way as any to look at Salcedo’s pieces: they have paid close attention to their original subjects, and have also distilled them to a point just shy of abstraction. This has been more or less the case in her work from the mid 1980s untitled series using pieces of reconfigured hospital furniture (with tiny plastic babies attached to it using animal fibres); to the bleak stacks of white shirts pierced by steel bars; to the Atrabiliarios series (1992–2004), in which shoes are displayed set into the walls of the galleries, each behind a veil of animal fibre; to the La Casa Viuda series (1992–95), a set of unhoused doors, sometimes with attendant fragments of other furniture; to the arresting Tenebrae Noviembre 7, 1985 (1999–2000), an earlier response to the Palace of Justice massacre, in which chairs lie horizontal, their legs elongated across the entire length of a room; and all the way through to the more recent Disremembered series (2014), shimmering, shroudlike tunics made out of raw silk thread and thousands of burnt needles.

‘If you’re working with readymades,’ of course, she says, ‘you’re not in either field: not abstraction, not figurative art – you’re sort of in between.’ Helen Molesworth’s fascinating essay in the catalogue for a major recent retrospective untangles the relationship between Salcedo’s work and the Duchampian readymade, and indeed Salcedo (while she insists she does not work with commodities: ‘I come from a poor country; I work with poor objects’) often obscures her authorial role. When we meet in Texas, she is in the middle of the exhausting and pitfall-strewn process of installing her retrospective at the Pérez Art Museum in Miami (until 17 July) and emphasises her feeling of fruitful estrangement from her own work: she must decide where to place the pieces, what dialogue to create between them, and in doing so, she takes each one as a found object, not as an object that I made myself. It doesn’t have any impact on me, the fact that I made it.’ Partly because the works are so often ‘made out of readymades and out of stories that are not mine either’, they feel received. She doesn’t, she jokes, react to them in a spirit of, ‘Ah! My child!’

She also doesn’t usually attempt to control the reception of her work: ‘an authoritarian dream’. When I ask about the interpretive statement she provided to accompany Shibboleth (2007), the notorious mesh-filled crack in the concrete floor of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, she indicates, tactfully, that a certain English empiricism made it necessary (as anyone who remembers the press coverage at the time can attest). ‘The problem we had at the Tate was that people were curious about how this was made. Most of the attention was on the technical aspects of it. So that’s why I felt I had to divert people from that very simple, very simple-minded way of looking at it.’ She is full of praise for the Turbine Hall itself, however, and for the Tate’s achievement in creating a real ‘public space that people feel they’re entitled to. There aren’t that many in the world.’ The more public, often ephemeral works she has been creating over the last decade or so – with the help of a group of assistants, ‘mostly architects’, who have worked with her in her studio for years – are consistent with that aim, and she is unusual in not working very often in multiples, and in refusing to sell her working sketches.

Her New York gallerist has been quoted going so far as to say, ‘She doesn’t do drawings. It’s just not part of her work.’ When I ask about selling them, Salcedo replies, ‘Actually I don’t even show my drawings: they’re private,’ and notes that, because she is trying ‘to truly consider the value’ of the individual lives her work commemorates, ‘I have to keep that memory in the most precise and delicate possible place. If that gesture were to be repeated a million times in order to sell it, then it would be destroyed.’

Detail from Atrabiliarios (1992–2004), Doris Salcedo. Courtesy Peréz Art Museum, Miami; © the artist

But she is resistant to any notion of the expansion of her work into the public sphere as a fundamental change or development, just as she refuses to give special significance to her decision, in her newest and still ongoing work, Palimpsest (2013–present), which deals with American gun violence, to use the individual victims’ names where she had earlier concealed them. ‘Art doesn’t develop as such,’ she says. ‘It’s not as if earlier work was less developed than later work – not in art history, nor in an artist’s history.’ Indeed, the thread in her own work is perhaps unusually strong. Describing her formation in Bogotá (where as an undergraduate, under the influence of the painter Beatriz González, she pursued a rigorous double degree in fine art and art history, which she says was considered unusual) she mentions that, though the connection might not seem as obvious as that with, say, Goya, Cézanne was extremely important to her for his structure and consistency. She still admires ‘the solidity he gave to Impressionism. He wanted to make it as structural as classical art without being classical. The care, the fact that each brushstroke was of a colour that was prepared on the palette, not just applied, the devotion to every single area of the canvas.’ And most of all, she says, ‘his coherence throughout his life’.

In the end, Salcedo believes, ‘It’s a myth to say that artists have choices.’ Even in the writers you learn from, in a sense, ‘You only encounter whatever you already know,’ and that’s how a connection with any work is established. ‘You have one perspective, your own perspective, and no matter how much you try to expand it, that’s it: that’s what you have, and from there you see the world.’ There’s a radical simplicity to this, of the same order that’s visible in her work – a sense of how much can be seen and understood by standing firm in one place. ‘You do what you can,’ she says. ‘And you can do one thing.’

Doris Salcedo is the first recipient of the Nasher Prize, an annual award for sculpture.

‘Doris Salcedo’ is at the Pérez Art Museum, Miami, until 17 July.

From the June issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here