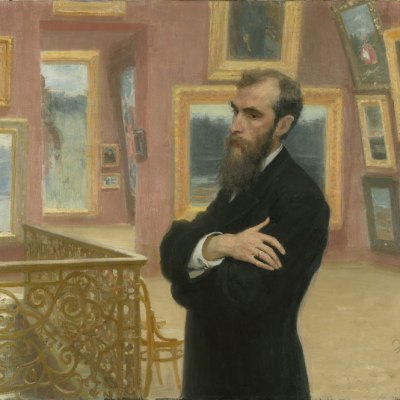

The first meeting of the Artists’ International Association, in 1933, took place in Misha Black’s bedsitting room in Seven Dials, long before his OBE and designs for the Victoria Line. They met by candlelight, because Black’s electricity had been cut off, and sat on fruit boxes stolen from Covent Garden market. The gathering was inspired by a chance encounter on the boat back from the USSR between Clifford Rowe, a painter struggling to reconcile his socialist convictions with his artistic practice, and Pearl Binder, the artist daughter of Russian-Jewish immigrants. Binder had been in Moscow to show her images of London working-class life at the Museum for Modern Western Art – an honour for a woman – while Rowe had gone to see something of the place American Communist friends had told him about. On the last day of his intended week-long visit he saw his own posters for the Communist book shop in London on display in the Foreign Workers’ Publishing House. They gave him a job and he stayed for 18 months.

Rowe had gone looking for something – and he believed he had found it; not only a political system but a model of future practice for artists. He left only because ‘they did not really need me. The class struggle was really going on back in England.’ He envisioned a unified organisation of artists in London, like New York’s John Reed Club, which would work to counter the despondency that had set in after the 1931 election, not least among artists themselves. The national government was pursuing extreme economic policies: deflation and unpopular cuts to unemployment pay. Factories stood empty. Oswald Mosley’s party had just announced themselves as the British Union of Fascists.

Anxiety over the seemingly entwined plights of society and art was expressed in the pages of magazines like The Listener, where Kenneth Clark and Herbert Read argued over the merits of Cubism, Superrealism (Surrealism), and academy painting, but for younger artists and art students the concerns were personal and pressing: a sense of responsibility to each other, and to the working class, a desire to create art that could speak to the common life of men and women, and the difficulty of surviving given those conditions. Black wrote later of ‘the feeling that the political situation was becoming intolerable’. Hitler was ascending, the depression ‘hung over us all’. Britain’s manufacturing production had never recovered its 1913 levels, while the numbers of unemployed – millions of people – stayed above 10 per cent even through the 1920s. Hunger marches took place in London in 1922, 1929, 1930, and the biggest of them all in 1932.

Hunger marchers in Hyde Park (1939), James Boswell. © Estate of James Boswell

Young artists, who hoped for patronage and influence, found themselves on the wrong side of their times, the glamour of their profession fading in the face of economic decline. Their experience – and few of the AIA artists were from well-off families – was of deprivation; like Orwell they could say ‘economically I belong to the working class’. Those who made any money made it from their commercial work – designs for posters and book jackets. It was very far from the days when professional standing meant a reliable income, when the Victorian painter Augustus Egg, on hearing he had been made a Royal Academician, leapt into a cab shouting, ‘My fortune’s made! My fortune’s made!’

James Boswell (1906–71), a native of New Zealand who had come to London to study at the RCA, recalled the happy contrast of the Second World War when it came bringing commissions and a social forum for art, compared with the ‘less prosperous days; remembering the difficulty of making ends meet between the wars […] remembering the long trudge from studio to agency to get the job that was going to pay the rent’. William Townsend, who became the Euston Road School’s landscape painter, despaired of making rounds of galleries and art editors, seeking commissions and ending up ‘in the ranks of the unemployed’.

Yet the AIA weren’t explicitly concerned with promoting fine arts. In their manifesto, published in 1934, they described their ambition to counter ‘imperialist war on the Soviet Union, and Fascism and colonial oppression’ by providing graphic materials: posters, illustrations, cartoons, book jackets, and so on. Their intentions, initially, were purely propagandic. James Holland, a founding member, thought the ‘only realistic course’ was to ‘discredit a system that makes art and culture dependent on the caprices of the money markets’, preferable to ‘continuing to paint until overtaken by starvation’ or giving up altogether. Although many members sensed that the broken dialogue between artists and the public would see a turn to realism, painting was not prioritised over other forms – photography, drawing, printmaking – nor the canvas and gallery over the banner, pamphlet or magazine. The notion of ‘fine arts’, indeed of ‘artist’, was troublesome. Even among those who would shortly after find their way back to painting, there was a lack of confidence. William Coldstream wrote that the slump ‘caused an immense change in our general outlook […] I became convinced that art ought to be directed to a wider public; whereas all ideas which I had learned to regard as artistically revolutionary ran in the opposite direction.’

Many were running as far as they could from the conventions and theories of the previous generations. James Boswell left the RCA twice during his studies in the late 1920s, the second time for good. ‘You can have no idea how provincial and awful London was,’ he later wrote. ‘Painting was dreary, academic and rubbishy.’ The writer Montagu Slater remembered meeting him in 1929, walking through Regent’s Park, wearing a shepherd’s scarf and carrying a large rocking chair. Slater found him an intriguing and contradictory figure: an art student who was also proudly colonial; a lover of romantic folk tunes and dirty music-hall songs given to desperate prophecies about world crisis and the fall of the Roman Empire; a man who would abandon painting for his political convictions, yet work for Shell (where he was the star of their publicity department in the late 1930s) in order to support his family.

Hatton Garden luncheon, for ‘Left Review’ (November 1934), James Boswell

After his second departure from art school, Boswell studied under Freddie Porter for some time but in 1932 he stopped painting altogether, deciding to focus on the graphic arts. With two other Jameses – James Fitton and James Holland – they formed the graphic core of the AIA, whose membership had swelled from a nascent 32 to almost 1,000 by 1936, though most of those exhibited with the AIA out of political feeling – Laura Knight, Henry Moore – without making the struggle their primary subject. The AIA expanded as the political moment grew more pressing (the Spanish Civil War galvanised many artists around the association), though those near the centre would still draw the distinction between ‘free artists’ and those like them who were ‘engaged’ or ‘in the struggle’.

The AIA’s first exhibition, ‘The Social Scene’, was held in a Charlotte Street showroom in 1934, and included paintings, photographs, and satirical cartoons. Boswell exhibited his picture of hunger marchers protesting against the Means Test in Hyde Park. He’d attended the demonstration two years previously, but in what would become his trademark style, the event is seen obliquely: in the foreground a man examines his shoe. Herbert Read was scathing about the quality of the work, but offered to give them a lecture on abstract art (the AIA was used to condescension, and he wasn’t entirely wrong about the standard of painting). Politically, the artists were attacked from both sides. Left Review accused them of showing more feeling for the political movement than for the working class itself; the Catholic Herald denounced the show as nothing more than propaganda, to which Eric Gill responded by calling for recognition of all art as propaganda: ‘Art which is not propaganda is simply aesthetics, and is consequently entirely the affair of cultured connoisseurs. It is a studio affair, nothing to do with the common life of men and women.’

The three Jameses turned to satire and illustration as democratic means of representing and critiquing politics and everyday realities. Mass media, which for them meant magazines, allowed their work to be widely and cheaply disseminated at little cost to the public, and the documentary spirit of the times offered a new conception of a socially useful form of art. If the artist needed to efface himself, he could be closer to the camera or the film reel; if all art was propaganda he could make himself the instrument of good. The AIA members confidently chose radical politics rather than radical aesthetics; their slogan at one point ran ‘Conservative in art and radical in politics’. Conservative in art didn’t mean entirely conservative in subject matter – depicting art’s usual subjects unflatteringly and its less usual thoughtfully was still subversive – but they were suspicious of European avant-gardes, preferring the social realism that was taking hold in America, or the German Neue Sachlichkeit of Otto Dix and George Grosz.

Boswell, along with other AIA artists, attended James Fitton’s lithography class at the Central School of Art. The group met three times a week to learn the craft but also to talk politics. The two aspects met happily: lithography meant Daumier, for a start, a representative of social reportage as great art, of shabbiness made aesthetically interesting, as well as an atmospheric medium for representing a grimy city, overcast with smoke and fog. Theirs was not the city of Feliks Topolski’s London Spectacle (1935) with its ironic illustration of lofty ladies and gentlemen, but the London of Patrick Hamilton’s 1941 novel Hangover Square, where train stations smell of apples and magazines and on the street the steady evening rain promises dissolution between the passionless faces and the passage of buses.

In 1933 Boswell printed a series of eight lithographs. The Fall of London shows a desolate city, where small ineffectual figures struggle through squalor, darkness and anarchy, the urban landscape forbidding and distorted. Originally intended as illustrations for a book imagining a fascist invasion, Boswell’s images are more ambiguous and unsettling even than that. They point to fracture within as well as threat from beyond. By drawing on the lithography stone in thick crayon, Boswell used the process to get a dense sticky texture, and rich depths of black. The prints are half in shadow, and the shafts of light are no less disturbing, suggesting flashlights around corners, fire or electric catastrophe; illuminating the splayed bodies of the dead while blinding the living. A decade before the Blitz, Boswell conjured a fearful image of the city half-destroyed and panic-stricken. It’s almost unrecognisable, and – unusually for Boswell – there are no individuals among the mass and mobs, no clear distinction between countryman and enemy. As in his later images of the war itself, he disdains sentiment.

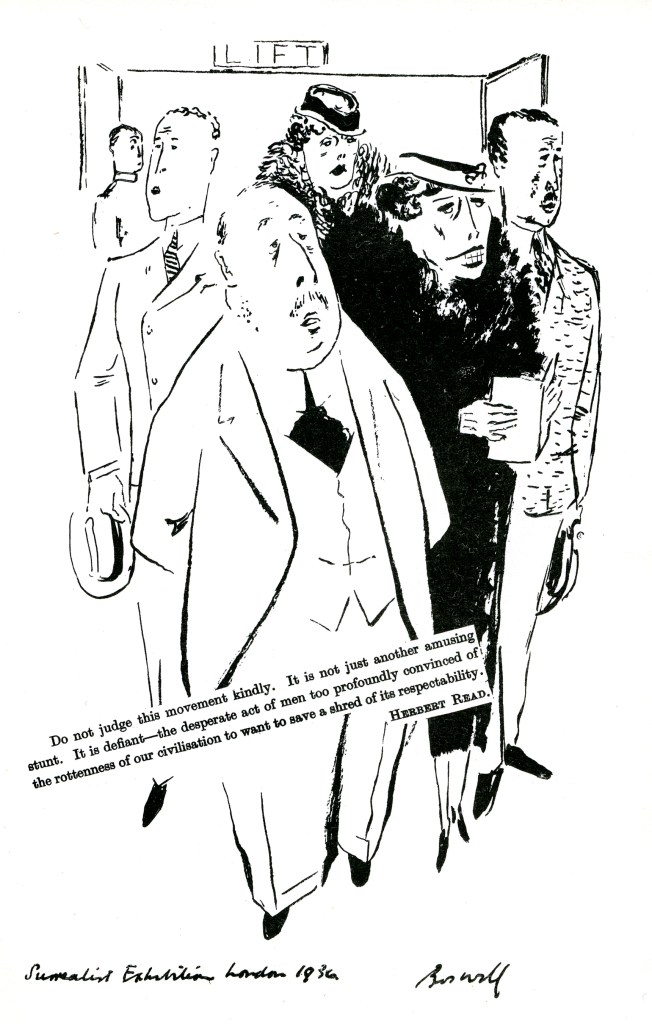

The Surrealist Exhibition, for ‘Left Review’ (July 1936), James Boswell

In 1935 Left Review ran his caricature of three of His Majesty’s Servants – government agents rendered as the shadiest of criminals – against Edith Tudor-Hart’s photograph Sedition? of a plain-clothes policeman openly recording a political meeting. Both directly attacked the 1934 Sedition Bill, which limited many aspects of public expression; Boswell’s image responds to the photograph, which infuriates the viewer, with a satire that derides its subject. In 1936 Left Review published 50,000 copies of ‘It’s Up to Us’, a pamphlet for peace designed by Fitton, Boswell, and Holland and inspired by Heartfield and Kurt Tucholksy’s 1929 Deutschland, Deutschland über alles project – uniting photomontage, quotations, and statistics to protest against government blindness to dangers at home and abroad.

Left Review survived for only a few years – from 1934 to 1938. During that time it was remarkable for allowing its cartoonists a full 16 pages of the magazine to pillory the establishment and promote their causes. Boswell’s subject was always the class enemy. To the first edition he contributed a scene of grim-faced businessmen stuffing their faces in Hatton Garden. It’s clearly indebted to Grosz, whose work was exhibited at the Mayor Gallery under the title ‘Social Satires’ that year: the disproportionate heads, areas of sudden dark shading, and use of feathery scratch and dot. But Boswell’s images are never quite as ferocious as Grosz’s; his indignation tempered by a greater sympathy for humanity, which renders it pitiful, rather than Grosz’s tendency to project self-loathing and complicity.

In 1936 Boswell scorned the opening of the Surrealist Exhibition by mocking both its detractors and supporters. His drawing shows a crowd entering the exhibition, dressed up for the occasion and frozen in complete befuddlement. Over the image he pasted Herbert Read’s warning commendation: ‘Do not judge this movement kindly. It is not just another amusing stunt. It is defiant – the desperate act of men too profoundly convinced of the rottenness of our civilization to want to save a shed of its respectability.’ It’s a neat juxtaposition – the helpless silly crowd, the sententious critic – both a case of the emperor’s new clothes, according to Boswell. Of the three Jameses, Boswell showed the greatest tendency to Rowlandsonian scabrousness in his drawings, and all had a taste for the absurd, which occasionally veered towards whimsy: their 1936 calendar declared them ‘A Triple Alliance against the Absurdities and Hypocrisies of the Existing Scheme of Things whose Shameless Intention is to Pillory and never to Please’.

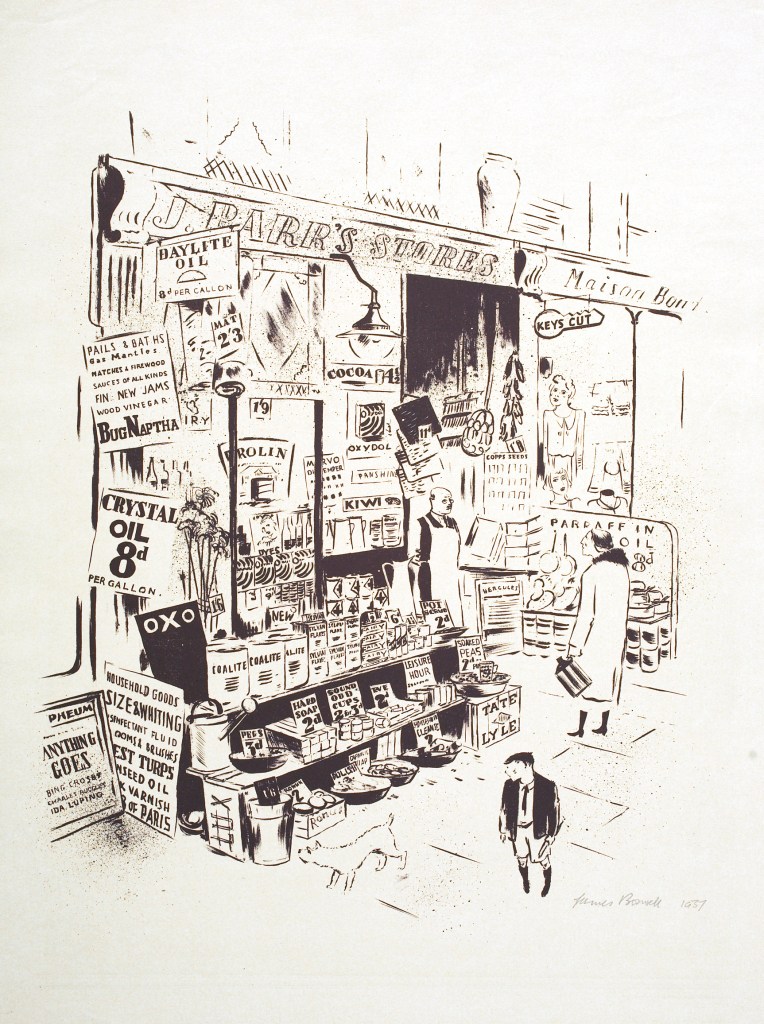

J. Parr Stores (1937), James Boswell. © Estate of James Boswell

Their attempt to reanimate the dwindling British tradition of social satire led to their association with the hugely popular magazine Lilliput, Graham Greene’s short-lived Our Time and the quarterly story magazine Seven, as well as the Daily Worker and the Daily Mirror. Good taste, they declared, was the enemy, for having ‘reduced English cartooning to emasculated illustration and religious hysteria’, yet formally all three remained closer to classic cartooning and caricature, albeit with expressionist flourishes, than the extreme vaudeville of Americans like Mabel Dwight and Carl Hoeckner, or the near Cubism of Boris Gorelick’s Sweat Shop (1938). Yet perhaps because of this their characters remained much more individual, more animated by their private concerns rather than simply types, even if their part in the drama requires a stock figure. Boswell excelled in his animation of bowler-hatted middle managers, empire builders with slicked-back hair and the cosmeticised wives of bankers.

Sometimes the ridiculous and the razor-sharp were allied to great effect. Beneath a 1935 article in Left Review on the press and mass hysteria, Boswell depicted an army major with a smoking machine gun for a face, next to a megaphone-headed press lord blasting out his diatribe, and a prim bishop topped by cross and skull. Despite a general incomprehension when confronted with the politics of surrealism, the humour of its literalisms and the possibility for visual storytelling and punning appealed to the British sensibility – it can be seen in Humphrey Jennings’ painting of a Swiss roll floating eerily over the alps, or Lilliput’s wonderful photographic juxtapositions: a picture of a lonely penguin opposite one of Lord Hankey, Minister without Portfolio, or a ripe pear opposite a jolly publican.

It’s easy to see this popular appeal in Boswell’s spotty youths, pub bores and street scenes, just as one sees it in Edward Ardizzone’s darts players and soapbox pontificators. But drawings like Ardizzone’s are much cosier than Boswell’s scenes, which even in his book illustrations retain their pointed social observation: greedy eyes, shiftiness, flirtation, how a boy watches a dog who watches something we can’t discern, while something else altogether is going on. His families are just as likely to be tired, drinking, existing on the backs of train lines or selling their clothes from a wooden fence, as happily converging in undifferentiated decency.

Much that Boswell and the AIA had feared for Europe came to pass and by the late 1930s, everyone was satirising fascism. But though the cause became common, the old hierarchies remained. The Everyman Print scheme launched by the AIA in January 1940 to provide affordable artwork to the masses (they were sold in shops not galleries) was commended by Kenneth Clark, but with a bite. The scheme, he said, also ‘enabled artists to become a little less high hat in their choice of subjects’. Perhaps he wasn’t entirely wrong to sneer – images of oppressed workers weren’t necessarily what workers wanted on their walls – but he was also commenting on the artists’s tendency to take their subjects from everyday life. Boswell’s Gitte Bisness, a market scene that became an Everyman Print, is full of his human touches: a tired woman sitting on a crate, a haggling pair having a stand off, a shady character in the background, two women on their way somewhere looking smart. His influential Hunger Marchers image became one too.

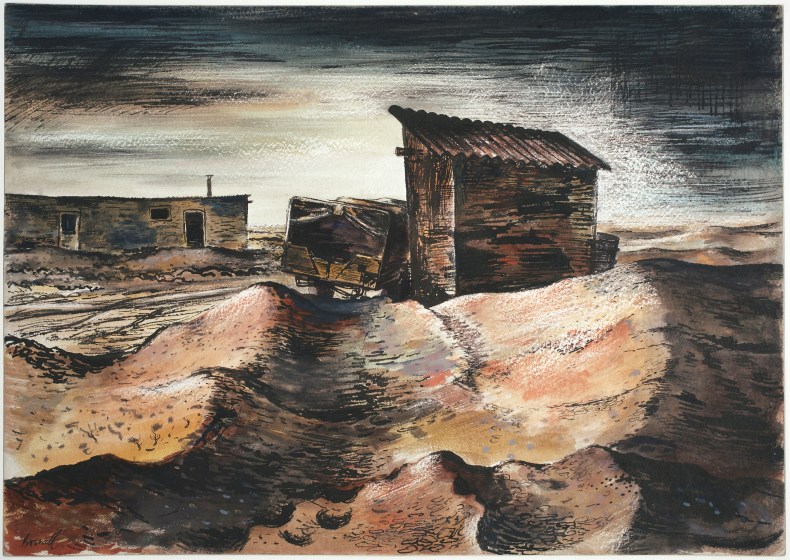

Lorry in the Desert no.2, Iraq (1943), James Boswell. © Estate of James Boswell

Boswell and other core AIA artists didn’t make Clark’s War Artist cut, though in the end this worked in Boswell’s favour: as well as his editorial and artistic steermanship of the Army Bureau of Current Affairs pamphlets, he produced some of the most stark, violent, and irreverent images of conflict, savaging British officers in particular. His paintings and sketches of Iraq, where he was sent as a radiographer, some of which are collected in William Feaver’s book James Boswell: Unofficial War Artist, show bull-headed generals, ennui, the eeriness of the desert, and the mind-numbing, dehumanising constraint of it all.

After the war much was achieved – the popular movement had paved the way for widespread endorsement of the ideals of the new Labour government – but it also preserved much that didn’t change: there was no revolution, no great social shift. The potential of the pre-war moment seemed to be lost. In 1947 Boswell wrote The Artist’s Dilemma, a short book which deplored the impossibility of making a living from painting and the necessity of commercial work that sapped the artist’s creativity. He resigned from Shell the same year and became art editor at Lilliput, where he gathered and nurtured such gently satirical talents as Paul Hogarth, Arthur Horner, Ronald Searle, and Gerald Hoffnung – and later had free rein at Sainsbury’s inhouse magazine. In 1964 he created the posters and propaganda for the Labour Party’s successful general election campaign, but otherwise moved further away from politics. He took up painting again.

From the May issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.