At some point in the future an explorer will cut their way through the undergrowth of a sprawling jungle on the site of Teddington, a few miles to the south-west of the remains of the city of London, and come across what looks like a fragment of an ancient Roman temple. A pair of pale brick columns, constructed with the headers facing outwards in a sea of mortar, and framed by shadowy pilasters, supports a narrow concrete frieze over primitive red clay capitals. Within the ruins a mysterious arched niche set into a rough brick wall clearly designates the site of a forgotten ritual. Who were these distant peoples and what did they worship?

The Teddington Folly, a back extension to a Victorian house, was designed by the architects Timothy Smith and Jonathan Taylor and completed in 2017; a current project of theirs incorporates elements from the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos into the rear of a terraced house in north London, a clever idea since the original from the fourth century BC is itself embedded into something else (in that case, the southern face of the Acropolis). Both projects draw on a long history of buildings that are intended to evoke a lost civilisation. John Outram has said that one of the ideas behind the juxtaposition of his Judge Institute in Cambridge with Quinlan Terry’s various classical buildings nearby is that eventually an intrepid explorer might encounter ‘a fragment of some giant metropolis unaccountably marooned in a little English country town’. But it is the smallest structures that are sometimes the most evocative, as if they were poignant hints of the failure of their builders’ grandiose intentions. The famous Kingsgate follies on the eastern tip of Thanet – ‘ruined’ convents, chapels and castles constructed in the 1760s for Lord Holland, a disgraced politician – were exactly that, according to the poet Thomas Gray, who saw these ‘mouldering fanes’ as Holland’s judgment, or curse, on his disloyal friends.

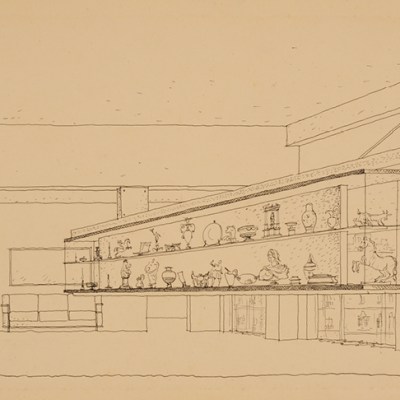

Teddington Folly, west London, designed by Timothy Smith & Jonathan Taylor Architects and completed in 2017. Photo: Ioana Marinescu

The Kingsgate follies are furthermore built of flint, which can have that atavistic quality to it that suggests something so ancient that there can be no way of knowing what on earth – literally – lies behind it. Perhaps this is the secret of the appeal of Skene Catling de la Peña’s Flint House, constructed as a guest house for the Rothschild family in Buckinghamshire in 2015. This building is clad in courses of flint that change in finish as they go up; the structure as a whole is wedge-shaped, and surmounted by a staircase like some Mayan temple; it dives into the ground and then re-emerges some distance from it, implying caves, or grottoes between or below. Buildings that look like inexplicable chunks of masonry, often inspired by Roman remains in Britain, have intrigued critics for a long time.

John Britton, the early 19th-century founder of analytical architectural history, came across Winnold House off Gallows Lane, near Wereham in Norfolk, and thought that he had discovered England’s oldest dwelling. This was a low, compact house, on an isolated and windswept location; it was actually mainly a Tudor farmhouse, but its east end incorporates some romanesque masonry from a 12th-century chapel. The effect is curiously haunting, and some architects appear to have emulated it. Lucy Marston’s Long Farm in Reydon, Suffolk, of 2013, which like Flint House won the Grand Designs House of the Year competition, is an interpretation of the medieval vernacular longhouse and has something of Winnold’s austere grandeur; so do Stephen Taylor’s Craddock Cottages in Gomshall, east of Guildford. These are located on a main road on the edge of the village, but their curious twisted forms, their irregular chimneys and fenestration, and especially their beautiful concrete lintels and sills faced with brick fragments, look in the context of their neat and mostly symmetrical neighbours like the sudden revelation of something ancient.

Flint House, Buckinghamshire, designed by Charlotte Skene Catling and completed in 2015. Photo: James Morris

Building follies in the more straightforward sense of ornamental structures has returned to fashion. The Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in California features them every year; some are more like identifiable buildings than others – Edoardo Tresoldi’s Etherea of 2018, for example, which took the form of three skeletal baroque rotundas. Maybe the precedent for that, and certainly for much else, was Venturi and Rauch’s Franklin Court monument in Philadelphia, steel frames that hinted at what Franklin’s long-gone house on the site might have looked like, and thus recreated it in ghostly form only. There is a recurrent theme in recent follies, derived from some of the most ancient ones, that the main part of the building lies elsewhere, or that one passes through a scarcely visible threshold to arrive at a place that does not exist: Adam Nathaniel Furman’s Gateways project of 2017 in Granary Square, a series of brightly tiled portals, was one of these.

But it is the raw and earthy quality of the best recent folly-like houses that bestows upon visitors that magical feeling of being on the edge of an out-of-time experience. There was some incredulity among architects last year when Adam Richards’ Nithurst Farm was not selected to join Long Farm and Flint House as a ‘House of the Year’. This sophisticated and powerful building was generated from a sense of wanting to recreate the odd atmosphere of Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker (1979), in which three strange men meander through a ‘Zone’ to seek out a magical wish-granting ‘Room’. Here too is a meditation on Nicholas Hilliard’s portrait of the 9th Earl of Northumberland, in which the earl lies in front of the Petworth landscape that surrounds Nithurst Farm, within a frame of trees and hedges that prefigures those ghostly house follies in Philadelphia. Nithurst stacks upwards to one side as the Flint House does, and employs in brick a variation on its stratified, archaeologically inspired walls. In terms of style, the windows come from another century and another country; a shaft of light from a hidden source illuminates the stairs within. If there is a building that exemplifies the intriguing allure of the British folly house, it is this one.

From the May 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.