In the first week of June, Britain and France played host to a vast spectacle on the 75th anniversary of D-Day. The commemoration events, tracing the timetable of the Normandy landings as they unfolded three quarters of a century earlier, marshalled a range of techniques, ancient and modern, to mark the occasion: church services, parades, fly-pasts, parachute jumps, gun salutes, fireworks, singing, dancing and speeches transmitted on live video streams and relayed by the world’s media. It was by turns jolly and sad, respectful and grotesque, full of national pride and internationalist aspiration. Yet despite this display of imaginative power, stubborn reminders of the obscenity of war leaked through in the snatches of testimony that were slotted into the news reports: ‘hospitalised with psychoneurosis after the war’; ‘my country made me a murderer’; ‘now I feel quite proud of it all’; ‘I was paralysed face down’; ‘one boy, about 17 years old, in the water bleeding and saying “I want my momma”’; ‘I was terrified’; ‘My God, I was never brought up to be killing people’; ‘I would give anything to be back with you.’ These are things that not even the myth-making machinery of some of the world’s most powerful countries can quite contain.

When official narratives fall short, artists working with the techniques of reconstruction can add to our understanding of violence, trauma and power. The Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz (b. 1973), a survey of whose work is currently at the Whitechapel Gallery in London (until 25 August), has long pursued an interest in creating counter-monuments, to people and stories that have faced various attempts at erasure. Since March 2018, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, Rakowitz’s replica of an Assyrian lamassu statue, destroyed by ISIS at the Mosul museum in 2015, has stood on the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square. Lamassus, protective winged deities with the body of a bull or lion and the head of a man, were placed at the gates of ancient Assyrian cities and palaces as a symbol of power more than three millennia ago. For archaeologists in the colonial era, this was heritage worth digging up and carting off to Europe – the British Museum, for instance, has the pair of winged bulls uncovered at Nimrud. These deities have been used to assert authority in modern times, too. The current US Iraq Command put lamassu images on their badges and logos (as did the British Tenth Army in Iraq in 1942–43), while Saddam Hussein made elaborate reconstructions of Iraq’s ancient heritage a part of his nation-building project. In its acts of destruction, ISIS was making a break with the past in service of a religiously pure future, but it was also placing itself alongside others throughout history who had the power, or so they hoped, to define meaning.

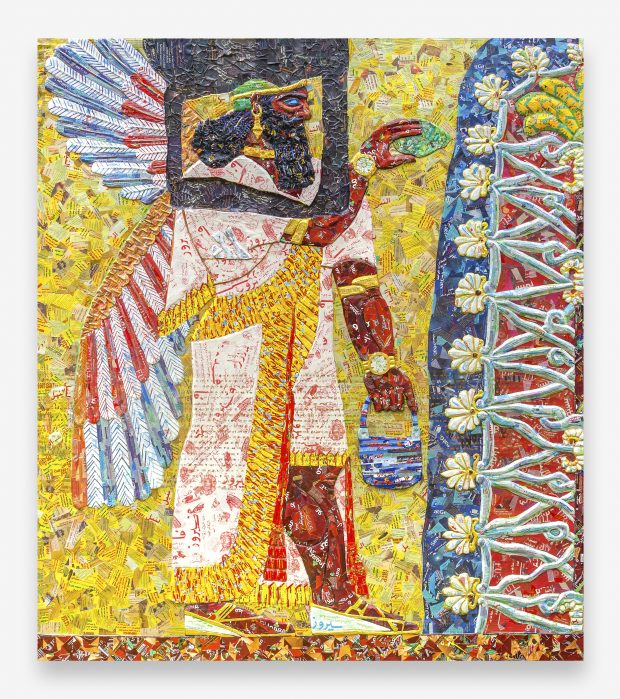

The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist (Northwest palace of Nimrud, Room N) (2018), Michael Rakowitz. Photo: Robert Chase Heishman; courtesy the artist; © Michael Rakowitz

Rakowitz’s winged deity undermines such pretensions, while making an argument of its own. Its surface is made from the brightly coloured cans of exported Iraqi date syrup Rakowitz remembers from his own upbringing in New York, in a family living a kind of double exile – first because they were Jews forced to leave Iraq as Arab states reacted to the creation of Israel, and second because they were later part of the Iraqi diaspora as relations between Iraq and the United States soured. At the Whitechapel, Rakowitz explained how during the period of international sanctions against Saddam Hussein, the cans could never be labelled ‘produce of Iraq’; the pretence was that they were from Lebanon or Syria, or further afield. Recreating the lamassu from these items is playful and defiant, but it also points to something broader about people’s everyday experiences of war. As Rakowitz pointed out, in Trafalgar Square the lamassu faces off against Nelson’s Column, whose bronze capital was made from the melted-down cannons of HMS Royal St George, and the lions at its base. It is a challenge: the hundreds of awkward little syrup-can labels with still legible bits of text refuse to be absorbed into the statement of military might around them.

The other installations at the Whitechapel derive their power from a similar juxtaposition of the monumental with the mundane. One room contains a large model of Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, made with debris taken from a demolished Aboriginal neighbourhood in Sydney. The effect is both mournful and utopian. Another displays plastercasts of stonework carved by Armenian masons in early 20th-century Istanbul, the hand movements of people whose community was destroyed by nationalism transmitted to the walls of a London gallery in 2019. Other exhibits deal with the precious books destroyed by bombing in the Second World War, the demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe public housing project in St. Louis, Missouri, and its replacement with low-density homes, and the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan. This is work about loss – of people, of places, of traditions and knowledge – and the potential of reconstruction not only to provide comfort, but as a protest against injustice.

Rakowitz has used the metaphor of a bandage, which both heals a wound and draws attention to its existence. The idea of injury and repair also features prominently in the work of Kader Attia (b. 1970), the French-Algerian artist, whose first major UK exhibition recently closed at the Hayward Gallery. The centrepiece of the exhibition was The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures (2012), which sets images of gueules cassées (‘broken faces’) – French soldiers who were facially disfigured during the First World War – alongside African busts showing ritual scarification and injury masks used in some communities for healing ceremonies. (Figures inspired by the gueules cassées have appeared in much of the artist’s work.) Attia sees the reconstructive surgery developed by doctors after 1918 as ‘a fantasy of modernity’, as he puts it in his catalogue interview; that we can repair damage in such a way that pretends it never happened in the first place.

At the Hayward, the installation was designed to echo an anthropological collection: objects were laid out on archive shelves, alongside books and magazines celebrating French discovery and adventure in conquered lands. ‘Repair’ in this sense has an obvious connection with the idea of reparation, not least because museums with collections amassed through colonialism are under more scrutiny than ever about how they deal with this legacy. Attia’s work, explored further in Hannah Gregory’s interview with the artist for Apollo in April 2015, suggests there will be no neat end to this. It would be better, Attia implies, to see repair as a constant, where the process of tending to loss and wounds is also a process of transformation; creating something new out of the wreckage of the past. It also requires accepting that there are points at which reconstruction may not be fully possible. The artist’s video piece Reflecting Memory (2016) interviews people who have undergone amputation about their experiences of phantom-limb syndrome, inviting viewers to draw comparisons between this type of individual pain and the collective trauma of a society that has suffered genocide or racist oppression to the extent that it is unable to recall parts of its own history.

Installation view of a bust inspired by soldiers disfigured in war (gueules cassées) by Kader Attia, at the Middelheim Museum, Antwerp. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin; © Kader Attia

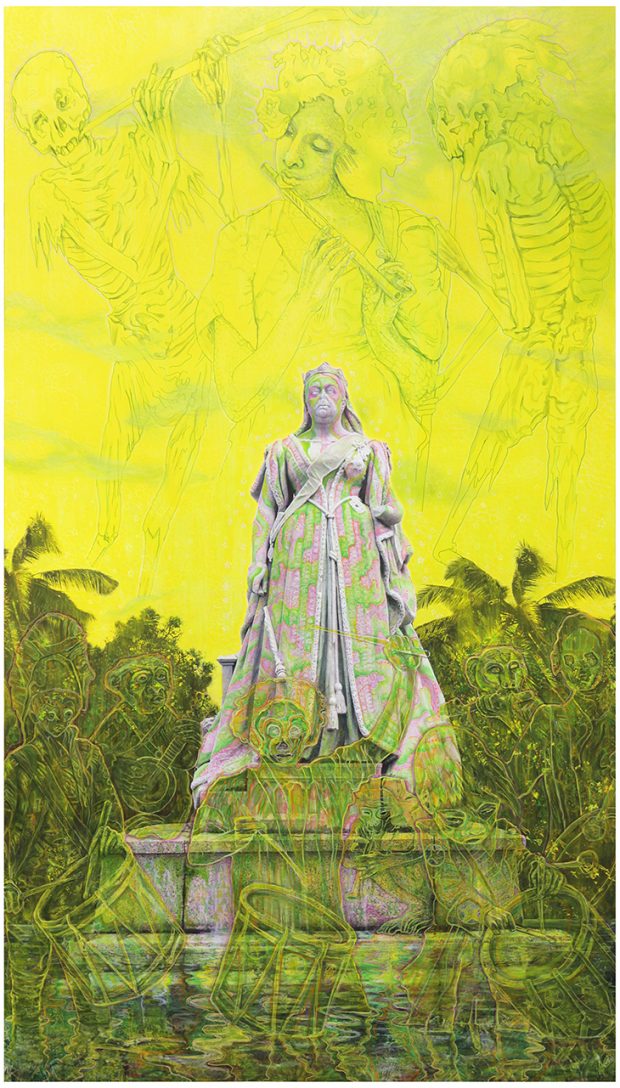

When crucial parts of history or memory are missing, however, artists have the option of trying to fill in the blanks – and are free to choose the degree of realism with which they do it. Like Rakowitz and Attia, Hew Locke (b. 1959), whose work ranges across sculpture, photography, painting and collage, uses reconstruction to raise questions about lost or erased histories. One of the highlights of his survey exhibition ‘Here’s The Thing’, which ran at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham earlier this year, was a room with dozens of intricately crafted model sailing ships suspended from the ceiling, their sails adorned with drawings that evoke Afro-Caribbean spirits and rituals (Armada, 2019). Locke is British, partly of Guyanese heritage, and spent his formative years in Georgetown just as the country became independent from the UK. In a BBC radio interview this March, he explained that the experience of seeing Guyana discard its colonial heritage and embark on a project of nation-building – and how often, by the way, do we see nation-building presented as a project of reconstruction, of revival, rather than invention? – had a profound impact on the way he views Britain, in particular the nostalgia and euphemism with which the country treats its own history. Hinterland (2013) uses a photo of the statue of Queen Victoria that stood outside the Georgetown law courts until independence, at which point it was dumped in the city’s botanical gardens. Locke has painted over it in acid colours and also sketched out a colonial danse macabre, which he describes as ‘the ghosts of Empire’, around it. Ghosts, or other intrusions of the past into the present, characterise much of Locke’s work. Another of his projects, begun during the financial crisis of 2008, involves buying up antique government share certificates from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and then adorning them with jigsaw-puzzle pictures of Africa and South America, or pictures of tribal statues atop modern container ships.

Hinterland (2013), Hew Locke. Image courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery; © Hew Locke. All rights reserved, DACS 2019

HMS Belfast, the Royal Navy cruiser now moored on the River Thames and repurposed as a museum, made several appearances in ‘Here’s the Thing’. The ship is famous for its role in the Second World War – it was the largest Royal Navy vessel to take part in D-Day, in fact – but Locke is particularly interested in a later episode. HMS Belfast passed through the Caribbean on its last voyage outside Europe in 1962, just as several islands were preparing for independence. Locke’s film The Tourists (2015) documents the changes he was allowed to make to HMS Belfast’s permanent exhibition, which includes a set of mannequins performing all the tasks that sailors on board would have performed on the working ship. Locke reimagined the 1962 voyage as if the ship had arrived in Trinidad in time for carnival. Calypso music echoes spookily on the soundtrack while the camera pokes its way into the cabins and corridors. The mannequins have been adorned with intricate masks or their faces tattooed. The work is an allegory for the nation – a ship on a voyage, hidden histories resurfacing – that maintains respect for life at an individual scale. ‘These are real people,’ Locke explains in the exhibition catalogue, ‘doing an extremely boring job most of the time, but for half a day or half an hour it can become terrifying. It’s as much about their inner fears, and their way of coping.’

On the anniversary of D-Day, the 16 countries that participated in the original battle issued a joint statement pledging never to repeat the ‘unimaginable horror’ of the Second World War. This is a curious way to phrase it. The horrors of war, on different scales in different places, have continued to befall people since 1945, with many of the above countries as participants or even instigators. And war is frequently represented, in extreme detail, across the range of media at our disposal. If there is something we are failing to imagine, then it suggests – as these artists do – that there might be better and more productive ways of confronting the past.

From the July/August 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.