Visitors to ‘Cute’ are invited to the show under the beneficent gaze of an AI-generated kittenicorn with a golden horn, a rainbow pelt and six adorable paws. For plenty of people, this billboard will be all they need to know – an instant draw or repulsion depending on their own cuteness polarity. But beneath the sparkly skin, ‘Cute’ is far from the featherlight confection it might appear. With something for almost everyone, it is eminently worth a visit even if you count yourself among the haters.

There is no denying that much emphasis is on celebration here, but the ambition behind Claire Catterall’s curation is broader and more multifarious than an invitation to coo. The result is one of the most academically ambitious and theoretically dense exhibitions I have seen in a long time. And it features tons of kittens. This is, on one paw, a historical show about the genealogy of cute; on another paw, a show celebrating cute capitalism; on another paw again, a sceptical show touting the emancipatory power of cuteness from that capitalist system; and on its fourth paw, a group show of contemporary artists whose work touches on the cute.

Playing dress-up with AI (2023), Graphic Thought Facility. Featured as the poster image for ‘Cute’ at Somerset House

It is, as the phrase goes, a lot. Crammed into the subterranean Embankment Galleries, there is a disco, a second disco, a games arcade, a ‘dedicated plushie space’ in tribute to Hello Kitty™, five cuteness themes (Cry Baby, Play Together, Monstrous Other, Sugar-Coated Pill and Hypersonic) and a set of specially commissioned pieces by artists including Ed Fornieles and Bart Seng Wen Long. Displays range from early manga illustrations through to transgender chimera glamour shots by Juliana Huxtable, via the collectible anthropomorphic figurines known as Sylvanian Families, a Pussy Riot balaclava, Bambi, and Hitler. As a whole, it is so busily polymorphous that I had difficulty deciding whether the two Harajuku Bo Peeps I encountered in the plushie space were performers or fellow visitors. Taken in one viewing, it is playful, insightful and a tiny bit nauseating.

The genealogy is sketched out in a line that runs from evolutionary psychology to the work of artist Yumeji Takehisa (1884–1934) and the emergence of kawaii culture in modern Japan. While the word ‘cute’ in English derives, oddly enough, from the same root as ‘cut’ and ‘acute’, with long since muffled overtones of sharpness, kawaii means something more like ‘loveable’, which gets to the heart of the matter. It is an aesthetic not of desire or of Kantian ‘disinterested pleasure’, but of affect. It is easy enough to trace it to what ethologist Konrad Lorenz termed the Kindchenschema (‘child schema’) of physical characteristics: big eyes, stumpy limbs, outsize head and uncertain movements; all of which quite reliably bring out an urge to nurture and protect. If it seems odd that it took until the mid 20th century for such a thing to be formalised, Isabel Galleymore points out in her insightful catalogue essay on the ‘ABCs of Cute Studies’ that Charles Darwin had examined the same characteristics in 1872 as inducing ‘tender feelings’. As any parent knows, this is a double-edged sword: the painful joy of loving something vulnerable so much that it makes you vulnerable too, tender in the fullest sense of the word. Cute as an aesthetic plugs into just this feeling – up to a point.

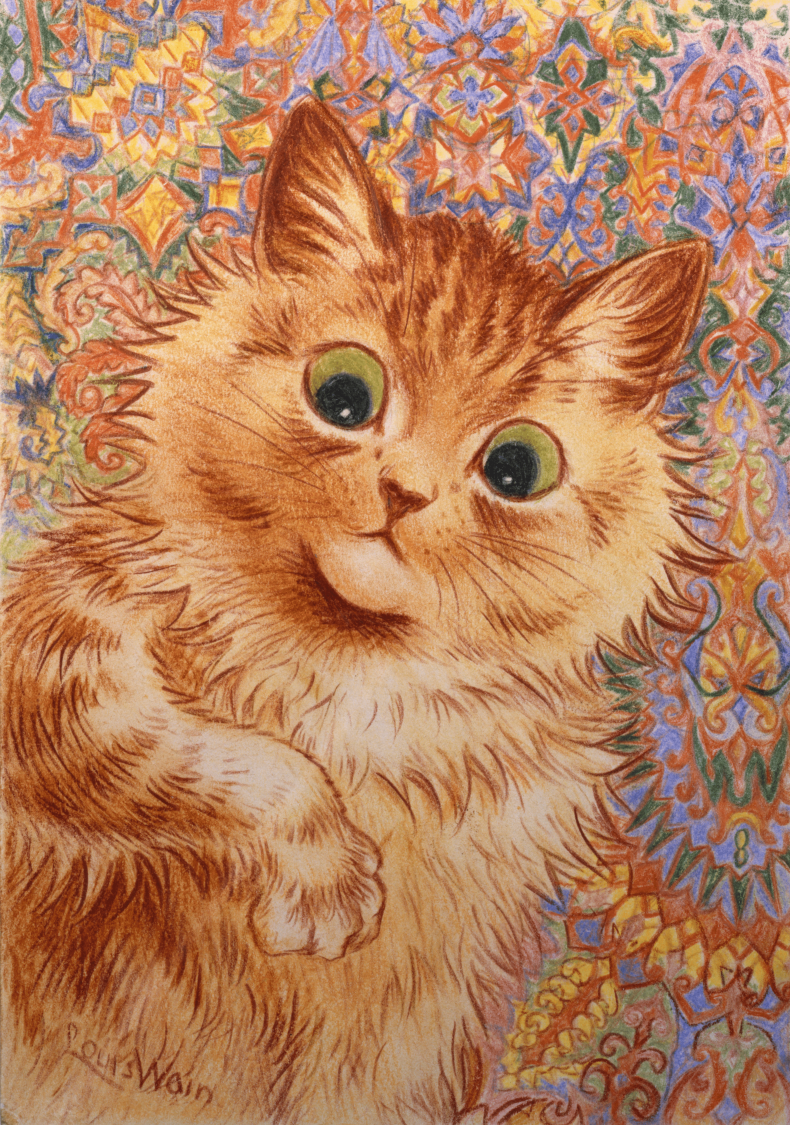

Evolutionary roots only take you so far. There is, as the show makes clear, much more to cute than tenderness. In the commercial age, cuteness revealed itself as one of the most marketable aesthetics available: it tugs on our heartstrings to get to our wallets. Hence the lineage from Louis Wain kittens to Furbies, Dogecoin and beyond. A superb Walter Benjamin quotation offered by writer Gabriella Pounds in the exhibition catalogue reminds us of his theory that if ‘the soul of the commodity’ were real, ‘it would be the most empathetic ever encountered in the realm of souls’: in every person it encountered, it would meet a ‘buyer in whose hand and house it wants to nestle’. Wide-eyed, trembling, nourished on money, it would probably look a lot like Hello Kitty.

Door to Cockaigne (2022), Julien Ceccaldi. Photo: Robert Glowacki; courtesy the artist and Modern Art, London

The natural corollary of this is that the cute is both manipulated and manipulative. Its aesthetics are prone to exaggeration (especially of the Margaret Keane ‘big eyes’ painting type) and falsification (cuteness as costume). For this reason, it borders on the uncanny and the grotesque, and can often cause not tenderness but repulsion. There is good reason, as Mike Kelley’s Ahh… Youth! (1991) suggests, to be sceptical of fetishising the supposed innocence of cuteness – a strand that feeds into Catterall’s thinking and cuts against the saccharine pseudo-sweetness that might dominate otherwise.

There is a lot to think with and about here, and it would be slightly churlish to complain about inconsistencies. But it does also feel like a show that is trying to have its cute and sell it too. This is a celebration of cute’s commodification that is also trying to make a case that ‘Cuteness thrives within the neoliberal capitalist structures which spawned it, while at the same time undermining their very foundations with its light-hearted affirmations of uncertainty’. This feels more like wishful thinking than anything else. The only thing undermining neoliberal capitalist structures on the day I visited was the magnificently surly personage manning the giftshop.

Overall, though, ‘Cute’ makes a compelling case for the seriousness of its subject while offering plenty to enjoy. A thoughtful viewer could, if they had the stamina, spend hours absorbing the displays here. It is both an exhibition for kids to run and dance through and one for adults to scratch their heads at. Hipster dads will stay for the Daniel Johnston cassettes, kids will stay for the games, and art lovers will stay for gems like Aya Takano’s The Galaxy Inside (2015) and Mark Leckey’s Dazzledark (2023). Others might just want to coo at all the kittens.

Ginger Cat (1931), Louis Wain. Bethlem Museum of the Mind, London

‘Cute’ is at Somerset House in London until 14 April.