The opening shots of Dahomey, the new documentary by French-Senegalese director Mati Diop that won the top prize at the Berlin film festival this year, recalls a film by Frederick Wiseman, the master of observational documentary. Still camera, direct sound, a series of what could be stock shots establishing location. We begin in Paris at night, with plastic models of the Eiffel Tower for sale on the street and a Bateau Mouche sailing along the Seine. Then, an on-screen message makes explicit the subject: on 9 November 2021, France returned to the Republic of Benin 26 treasures it had looted during the colonial period more than a century ago. For these items, the text says, ‘130 years of captivity are coming to an end’.

We then see the eerie corridors of the storage vaults of the Musée du Quai Branly. Some images are taken directly from footage on CCTV cameras in the halls and all we hear is the hum of the bright lights, recalling a hospital or prison. It is both banal and ominous. Then Diop breaks with the observational style to introduce a supernatural element, which is not a surprise for those familiar with her work to date. She has described this documentary as a ‘counter-narrative’ to the official restitution process, giving a voice to those who have been silenced, which includes people in modern-day Benin seeing some of their heritage for the first time and, also, voices from another world. The latter comes in the form of the internal monologue of one of the statues being cased up in Paris and packed on to a plane for Benin.

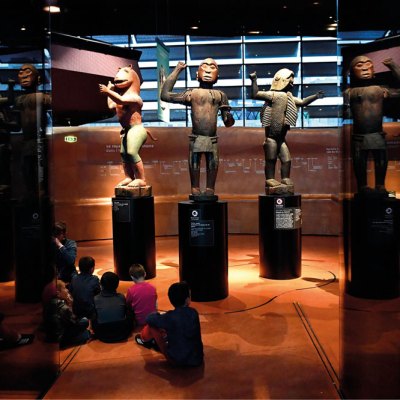

A still from Dahomey (2024), directed by Mati Diop.

This move from observational documentary to ghost story comes swiftly in the 68-minute film and the film keeps moving between the two modes. A voice speaks in the Fon language, while the screen is black, evoking the closed casket into which the statues are being packed; it tells us it has experienced ‘a night never so deep and opaque’. We learn that the voice, which refers to itself as ‘exhibit number 26’, is King Ghézo, who ruled the kingdom of Dahomey from 1818–59 and, in the afterlife, watched over the land in the form of this statue.

A sense of being watched over is central to Diop’s film. Her camera spends a lot of time looking at people who are discovering the statues for the first time – there are roadside celebrations when they first land and an unveiling in the presidential palace in Benin that lasted a few months and attracted 20,000 visitors. (Since then the repatriated artefacts have returned to storage in waiting for the opening of a new museum that has been continually delayed.) Diop has expressed scepticism with the pomp and ceremony that accompanied President Emmanuel Macron’s announcement about the return of the objects in 2017. She regretted that the coup de théâtre, so typical of Macron, stole the limelight from the decades-long efforts of campaigners in Africa to get their artworks back. These are the testimonies and reactions Diop wants to put in the spotlight.

A still from Dahomey (2024), directed by Mati Diop.

Born and raised in Paris, Diop started out as an actress, playing the lead in Claire Denis’s 35 Shots of Rum (2008). She turned to directing when she began reconnecting with her African heritage, and became frustrated with finding only stereotypes of Africans on screen, as well as a lack of films being made by people from the continent. Dahomey is animated by this spirit of reappropriation and it certainly offers a more nuanced than usual portrait of restitution, definitively breaking with the self-congratulating vibe pushed by Macron. She has clearly thought deeply about the issues and she is more likely to cite contemporary thinkers such as the decolonial feminist Françoise Vergès as influences on her work than film-makers. This suggests Diop starts from ideas, not images or a specifically visual project, and in Dahomey the results are uneven. It is at its best when observing people. In particular, the long sequences, again recalling Wiseman, that show students debating the restitution process and questioning how much they should celebrate the return of 26 objects out of tens of thousands. These are complicated questions without simple answers and the accounts Diop included in her film are compelling because we are given the time – and she has taken the time – to listen and look.

The debates were shot in a hall filled with students at the University of Abomey-Calavi. Among the speakers is one young woman who pushes back against the criticisms voiced about the returns just being a drop in the ocean. This, she says, slipping between French and Fon, downplays the role played by Patrice Talon, the president of Benin. First accept that you have got back a little, she says with conviction, then develop a technique to recover the rest. Shortly afterwards a male student counters her optimism, wondering whether, after 26 treasures have come back, maybe in another 100 years they’ll get two more items, and in 200 years maybe four: ‘But we’ll not be around anymore!’ he says to enthusiastic applause. The point is certainly pertinent given that the Quai Branly holds some 79,000 of the 90,000 African objects in French museums.

A still from Dahomey (2024), directed by Mati Diop.

For me, these scenes are the most powerful in the film, rather than the plaintive monologue of the statue of King Ghézo. Although this feature has been celebrated by critics as the most original element of the film, I could not shake the vague, and rather silly, echoes of Darth Vader. More importantly, the content of the monologue is too elliptical to pack any real punch. Dahomey is at its most compelling as documentary, when Diop tries less hard to force the ‘counter-narrative’ to the government’s celebratory performance and simply lets her camera, and her subjects, do that work by themselves.