David Bomberg’s luminous self-portrait from 1931 provides a vantage point from which to survey a career that found early success, but ended in bitter disillusionment. Displayed next to a pencil self-portrait from 1909 and anticipating the series of self-portraits he produced between 1954 and 1956, the painting offers a context in which to view the trajectory of his artistic development. It’s an apt opening to an exhibition dedicated to a seriously neglected artist – ‘Bomberg’, which opened at Pallant House Gallery in October last year, toured to the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle, and is now on its final stop, albeit in somewhat reduced form, at Bomberg’s spiritual home at the Ben Uri Gallery.

Self-Portrait (1931), David Bomberg. Photo: Justin Piperger; © The estate of David Bomberg/Bridgeman Art Library

The painting has a curious brightness, a quality shared with some of his landscapes, which here gives a radiant force to the artist’s presence. His confident pose hints at arrogance, and yet he’s elusive too – a mirage of shimmering brushwork allowing him to slip out of reach just at the moment we think we might be able to see him clearly. It’s an endlessly fascinating and bewitching work that gets at the trickier aspects of Bomberg’s character; his tendency to stubbornness and the experience of anti-semitism that dogged him throughout his life meant that he failed to ingratiate himself with the kinds of people whose patronage he so desperately needed.

The Broken Aqueduct, Wadi Kelt, near Jericho (1926), David Bomberg. Photo: Justin Piperger; courtesy Ben Uri Gallery and Museum; © the estate of David Bomberg

His rebellious nature worked in his favour early on, and his exhibition at the Chenil Galleries, Chelsea, in 1914 made Bomberg the only modern artist of his generation to have a solo show in the years prior to the First World War. The Mud Bath (1914) was hung outside, and is said to have alarmed passing traffic as much as the critics. Its highly abstracted figures composed of sharp lines and geometric patterns exemplify Bomberg’s radical break with naturalism, which earned the disapproval of his tutors at the Slade School who had thrown him out in 1913.

If Bomberg’s tutors felt that he would benefit from learning ‘a little more modesty and humility’, and were exasperated by his tendency to ‘theorise and analyse’, his pencil self-portrait from 1909 shows that if he were so inclined he could produce exactly the sort of drawing that the Slade expected. With its careful modelling and attention to anatomy, the drawing – made while Bomberg was taking evening classes with Walter Sickert – belongs to a tradition of draughtsmanship that extends back to the Renaissance.

Study for Ju-Jitsu (1913), David Bomberg. Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia. © The estate of David Bomberg/Bridgeman Art Library

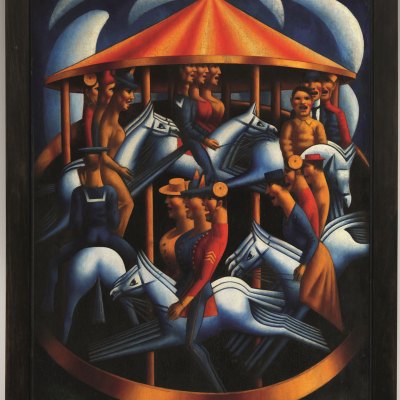

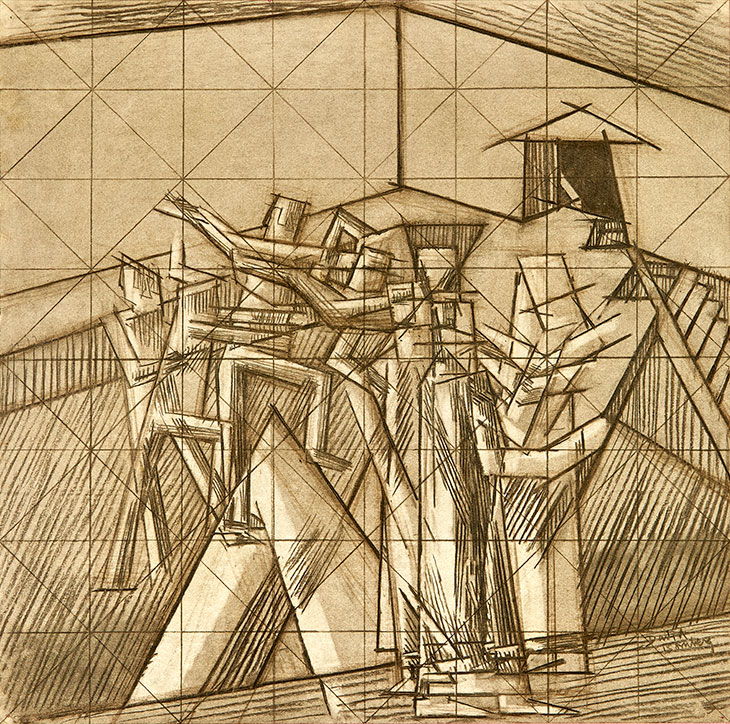

Bomberg was hardly alone in having been profoundly affected in 1910 by Roger Fry’s exhibition, ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’, which introduced a British audience to artists never previously encountered in this country. More remarkable was Bomberg’s almost immediate response to Fry’s second Post-Impressionist exhibition in 1912. This time the selection was rather more up to date, and the impact of both Futurism and Cubism is clear in works like Bomberg’s Cubist Composition (Two Figures), of 1912–13, and the frenetic, fractured space of Ju-Jitsu, from 1913.

The absence of finished paintings from this period before the war makes it hard to appreciate the strength of vision embodied in these early works, which in this exhibition are represented through drawings and small, less significant paintings. Even so, preliminary works, including a study for Ju-Jitsu, serve to underline Bomberg’s grounding in academic draughtsmanship, highlighting the way in which the grid structure of Ju-Jitsu employed and then subverted the centuries-old practice of squaring up a drawing for transfer to canvas.

Bomberg’s pre-war paintings reduce the human body to pure form, and that the trauma of the war encouraged him to consider anew its expressive capacity has become something of a truism. His monumental painting, Sappers at Work: A Canadian Tunnelling Company (1919) was initially rejected by the Canadian War Memorials Fund as a ‘Futurist abortion’ before being accepted after considerable reworking, and is represented here by two pen and ink drawings. While Gunner Loading Shell (c. 1916–18) and Sappers (c. 1919) both suggest an equivalence between man and the hardware of war, the figures’ postures emanate an intense, grim concentration that is both empathetic and incisive.

English Woman (1920), David Bomberg. Photo: Justin Piperger. Courtesy Ben Uri Gallery and Museum; © the estate of David Bomberg

When the Ben Uri was set up as a society in 1915 with the aim of supporting Jewish artists, it put Bomberg into contact with the businessman Moshe Oved. Oved not only enabled the society to acquire several of Bomberg’s paintings, but also commissioned from him a poster advertising Oved’s jewellery shop, Cameo Corner (1919). Bomberg worked on a number of other graphic projects after the war, and regular contributions to the ‘little magazines’ that sprang up at this time helped to hone a style suited to reproduction, characterised by strong lines and simple, clean forms. This new style informed his painting. In Barges (1919), the lines of the vessels and their reflections establish a rhythm that echoes across the piece. A series of paintings followed, with increasing emphasis on figures: the stooping women in English Woman (1920) and Mother and Child (c. 1920), placed within a geometric construction that both frames and constrains them.

Last Self-Portrait (1956), David Bomberg. Photo: Mark Heathcote. Courtesy Pallant House Gallery; © the estate of David Bomberg

Limited commercial success was alleviated in 1923 by a commission to record the progress of the Zionist cause in Palestine. Bomberg’s new environment captivated him; the paintings produced here reflect his fascination with bright sunlight, and the skylines of the Middle East. He remained until 1928, but his painting style was changed irrevocably, an earthy palette and a looser, more gestural application of paint characterising his late style. If his work received approval in the press, sales, as ever, were few. He turned to portraiture, and increasingly to self-portraiture. The final room of this exhibition is witness to an artist withdrawing into himself, the landscapes’ vivid colours and fleeting impressions of light and movement contrasting with self-portraits that become ever more veiled and indistinct as death approaches.

‘Bomberg’ is at the Ben Uri Gallery, London, until 16 September.