In the late 1990s, the painter David Salle (b. 1952) chanced upon an old opera backdrop painted with a sentimental Alpine landscape and found himself immediately drawn to it. He embarked on a series of paintings, the Pastorals, which contained snippets of imagery from this backdrop alongside imagery that Salle found in magazines, television, popular culture and elsewhere. The results were riotously colourful canvases that, at first, seem almost randomly assembled. They are full of figurative images but far from realist, and their arrangement reflects Salle’s continued pursuit of what he has called ‘a truly malleable, elastic pictorial space’.

Salle studied at the California Institute of the Arts in the 1970s, where he was taught by the conceptual artist John Baldessari, whose interest in found imagery can be seen throughout Salle’s work. Salle’s art also bears the imprint of Pop art, as well as demonstrating a considered approach to form that chimes with some of the abstract movements that emerged in mid-century America, including Abstract Expressionism and All-over painting.

For his latest series, Salle has returned to the Pastorals, using a specially made artificial intelligence program to reinterpret them as new works, which he then prints out and adds to with his paintbrush. These are on display in the exhibition ‘Some Versions of Pastoral’ at Thaddaeus Ropac, London, from 10 April–8 June. Salle spoke to Apollo before the opening about the newfound freedom he has enjoyed through discovering AI.

David Salle. Photo: Robert Wright

How did the original Pastorals come about?

I’m not someone who has been deeply engaged with technology. I had been committed to painting in the traditional sense for a very long time; however, I have, over the years, fantasised about a kind of very fluid pictorial space by which gravity and cause and effect and loss of perspective lessen their hold. Even some of my work from the early ’80s depicted figures at odd, extreme angles, lit in a very theatrical way.

I think that impulse found its expression, finally, at the end of the ’90s with a series of paintings based on this opera backdrop that I found by chance. The first version I made, I repainted the background in a very literal way, using the same colour, the same tones. Having made that painting, I then overpainted some disjointed or disconnected images on top of the colic pastoral scene.

I was very influenced by Warhol’s camouflage paintings, and I repainted the pastoral scene, breaking the image up into faceted shapes that lock together like puzzle pieces. I assigned to those shapes the colours from the camouflage paintings – in some cases two or three or four palettes in a single painting, which is yet another violation of one of the cardinal rules of representational painting, which is that you create a palette and stay consistent within that palette for the painting. So I was kind of showing off, like: ‘Oh no, I can put three palettes in a painting.’

And then those pastoral scenes formed, again, a kind of backdrop against which I orchestrated an additional suite of images and inset paintings. They’re quite complex, and when they work, they have nice, lyrical completeness to them.

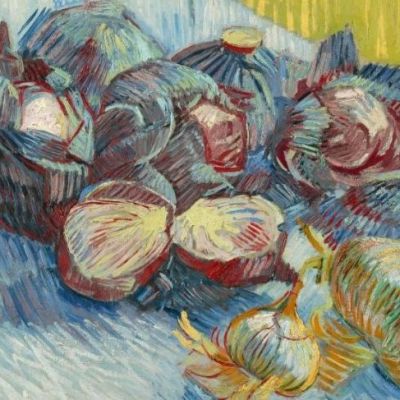

Five O’Clock (2001), David Salle. Photo: Tom Powel; © David Salle/Licensed by ARS NY

Why did you decide to use AI to reimagine the Pastorals?

I had been working with a company in New York – I guess you call them a tech incubator – to develop a digital game that would allow the user to access the power of juxtapositions. It never came to fruition, but in the course of working with these people, one of them said, ‘Hey, you really should check out this other thing that we’re doing.’ And that other thing was AI – this was the first time I had encountered it, this was two or three years ago. And it was very interesting, but also there was something a little bit too much like ready-made Surrealism.

When you say ‘ready-made Surrealism’, are you talking about the sorts of images that AI could generate at that stage?

Yes exactly: what AI is – or was at that point – is an averaging of all the billions of images downloaded from the internet. So it can access everything, but it doesn’t have any idea what it’s doing or what it means. So I typed in ‘a painting by David Salle’ and it made a very funny portrait of a man that sort of looked like something I might have done, and something Francis Bacon might have done, and also, in fact, something that had been liquefied and poured through a sieve into a beaker. You realise that the digital sphere has no bones. There’s nothing solid. It’s a liquefied world, which is what’s interesting about it. But at the time, I didn’t see any application for it, I just put it out of my mind.

Then a while later the company connected me to another young engineer called Grant Davis, who was working with AI from a different starting point. He was developing a program that did not rely on textual prompts. It was purely visual, and that, in a way, was the key that unlocked my access to this world.

When I saw how the machine functioned – which is to say, it scans for similarity and dissimilarity, which is very similar to how our own eyes and brains work – I realised that what it needs is something to scan that is already broken up into discrete bits. And I remember the original Pastoral paintings from 1999. I trained the machine on the Pastoral paintings and worked with this program, which is really just a lever that moves along the continuum from dissimilar to similar. When I moved the lever along the continuum toward dissimilar, the results were really exciting.

Red Scarf (2025), David Salle. Photo: John Behrens; courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery; © David Salle / ARS New York, 2025

How did the process actually work and how collaborative was it?

I don’t write code. I have no interest in doing that. The code is in the program, which is an invention called Wand, made by Davis. What I did was to train the Wand on the things I wanted it to know, and then when I fed it the Pastoral images, I simply asked it to make another version, and another, and so on. It’s very simple.

When the machine makes something that I recognise as having the potential for some kind of painterly intervention, I save it. We might create 500 of these saved images, and I print them out on paper. And then from that I might choose to print 10 on canvas at a certain size to test out the hypothesis that this configuration has something worth responding to. So in a way it’s using a technological tool to arrive at a starting point which is in its own way very traditional: a painting on top of a found photograph. In this case, the found photograph is a variation of an earlier painting of mine. It’s all me, distorting, redistributing, deconstructing, reconstructing elements. The machine only knows what I’ve told it. And since it’s a machine, no one’s feelings are hurt if you say no to something it’s produced.

How much intervening are you doing once the canvas is printed out?

Each painting is different. All that matters to me is the final result. In some paintings, there’s almost no digital information left; in others there’s quite a lot and in some of them it’s hard to tell exactly what’s painted and what’s not. The interface between printing and painting itself is certainly not a new idea; all that’s new is the technology behind the printing part of it.

Blue Trunks (2025), David Salle. Photo: John Behrens; courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery; © David Salle / ARS New York, 2025

When you talk about your ideal of a malleable pictorial space where everything happens at once – that seems to me the kind of thing an Abstract Expressionist might say. But your work is quite figurative. How do you think form and content interact in your work?

Most painters I know, when we talk about painting, we tend to talk about it without making a great distinction between those things which are figurative and those things which are abstract. It’s not that it doesn’t matter, it’s just that things are both: every painting is an abstract painting, fundamentally – it’s all shapes and their distribution on a canvas. And every abstract painting is also imagistic, because it’s the image of the abstract. It becomes confounding when we start to describe it, because then we get tied in linguistic knots.

I am, for sure, someone who paints recognisable forms – bodies, faces, clothes, objects, landscape – but my DNA as a painter is very much inherited from the energy of All-over abstraction, from the New York School painting of the 1950s. One way of describing it is that I want to make an All-over painting with the same immersive sense of continuity that one would find in a classy abstract painting from 1951, but I want to locate that energy in figuration. And to me, there’s no conflict. It’s simply two halves of the same thing.

I’ll tell you a funny story: the first time I met Richard Serra, I think it was in 1981, I was just starting to become somewhat known, and I was on a panel with him at ArtForum, with Julian Schnabel and a couple of others. At one point during the panel Richard said to us: ‘I know what you guys are trying to do. You’re just trying to combine Pollock with Warhol.’ And at the time I thought, ‘Oh Richard, stop being a bully.’ But years later I realised that he really had a point. And wouldn’t that be wonderful, if you could combine the two?

Suspenders (2025), David Salle. Photo: John Behrens; courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery; © David Salle / ARS New York, 2025

From what you’ve said in other interviews I’ve read, you seem to approach the AI program that you’re using as essentially another artist’s tool. Do you think there are any dangers of treating AI lightly? Or do you think that in 20 or 30 years’ time we’ll be wondering what all the scaremongering was about?

I don’t know. I don’t know if it’s possible to know. I don’t think it’s a tool like any other. But at a certain point in time, oil painting was a new technology. It was the invention that allowed painters to actually express what they were seeing. I’m not saying that AI is that kind of invention exactly – it’s obviously an invention of a different order, because it’s not something which was invented for painters. But the question is: can painters use it in a productive way? And what would the non-productive way look like? And what are the dangers of that? I’m tempted to say that the dangers are just the dangers of making bad art.

Did any of the more practical concerns around AI – artists’ work being used to train AI without their permission, or people making AI art to hang on their walls where once they might have bought a work made by a human, for instance – come up when you were doing this project?

My answer is going to sound egotistical, and I don’t mean it that way. In the process of familiarising myself with the technology, I looked at a lot of digital art, and none of it was interesting. That doesn’t mean that I’m the only person to have the necessary talent to use it, but it means that people approach it in a way that was generalised. And the one thing that I think is true about art, no matter what the form takes, is that generalisation leads to bad art.

So when more artists start using these tools, we’ll see that degree of specificity. And I think a lot of interesting things will come out of it. But a lot of people who aren’t artists will also be playing around with stuff – so what difference does it make what they do or don’t do?

As AI becomes more sophisticated, the question is: will it reach the point where the results are indistinguishable from human artists? I’m sure there are technology advocates who would say, of course it will. I’m very sceptical. I’ve been on enough panels with tech people and have seen what they think art looks like – trust me, the art world has nothing to worry about.

N.P. Intrigue (2025), David Salle. Photo: John Behrens; courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery; © David Salle / ARS New York, 2025

What has been the response to these works? Have you had any negative reactions from, let’s say, artist friends, around your use of AI?

No. Well, no one said anything to my face. I think we’re past that point. I don’t know how accurate this is but, to take another historical analogy, I know that when Pop art emerged, there was tremendous pushback. It was the end of art. It was dumbing down the culture. And some people were convinced that Pop art had ruined art forever. But now many decades later, you can see that there’s good Pop art and there’s less good Pop art. They’re operating under the same premises – the world of commercial imagery is interesting and we can present this graphic reality as painting – but sometimes the results fall flat, and now, 60 years later, the difference is very clear.

How do you think using AI has changed your work, and affected how you think about art?

Painters change over time, and there’s this concept of late style, which, in painting, usually refers to a time when the painter lets go of certain requirements. I’m very close friends with Alex Katz and there’s a painting hanging in the foyer of his loft from the 1960s that’s full of very tiny details. The paintings he’s doing now are much more gestural, often just a brush stroke. Last time I was at the house we passed by the earlier painting and Alex pointed to it and said: ‘Can you believe the amount of trouble we used to go to back then?’

I’m not as old as Alex, but I’m older than I was when I started and I feel like I’m experiencing the beginning of a kind of late style. What that means is figuring out what’s important, not getting bogged down in the weeds.

I think these new pastoral paintings are so much looser, so much freer. They’re much more direct. If I had discovered AI 20 years ago, maybe the results would be very different. But as it is, it’s coming to me at just the right time in my evolution as a painter.

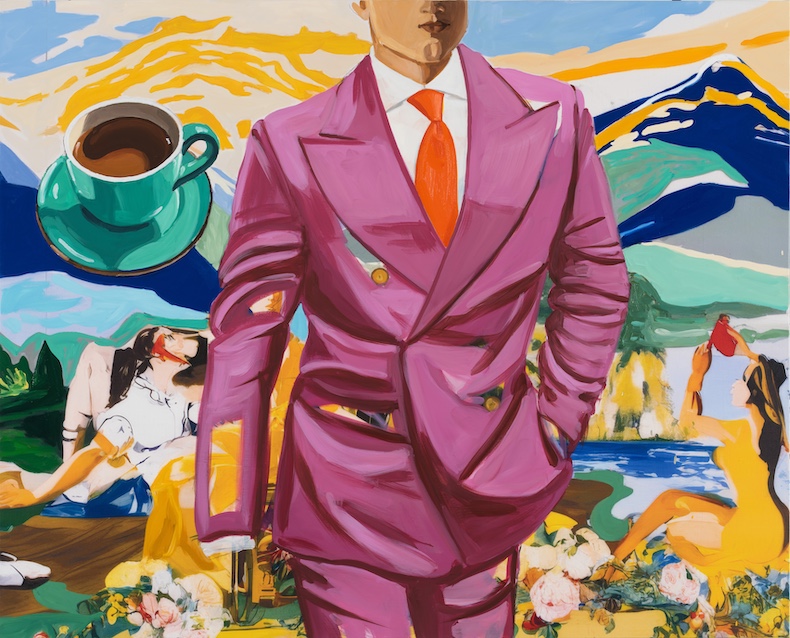

Power Suit (2025), David Salle. Photo: John Behrens; courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery; © David Salle / ARS New York, 2025

Do you think you will continue using AI in your work?

I feel very energised by these paintings and the underlying images that are part of how they’re generated. I see myself completely consumed with this for the foreseeable future.

To use a musical analogy: in jazz, there’s the standard, and then there’s the improvisation on top of the standard. And there are only so many jazz standards, and the quality of the reinterpretation and improvisation on top of that is where the soloist’s identity lies – not unlike, let’s say, the persona that’s included in a brush stroke. My point is that the AI background is just one in a long line of backgrounds that I have used in the past 40 years to improvise on top of.

I’m not interested in reaching a point where I just push a button and the thing makes the painting. That, to me, just wouldn’t be interesting. I want to play the solo, whatever it sounds like. And I think when you see these paintings in the gallery space, they’re so clearly paintings – physical objects that have been made with a brush. There’s no mistaking them for something that was made in a test tube, and for me that’s the only thing that really matters.

‘David Salle: Some Versions of Pastoral’ is at Thaddaeus Ropac, London, from 10 April–8 June.